Cindy Sherman-The Woman Who Wasn’t There

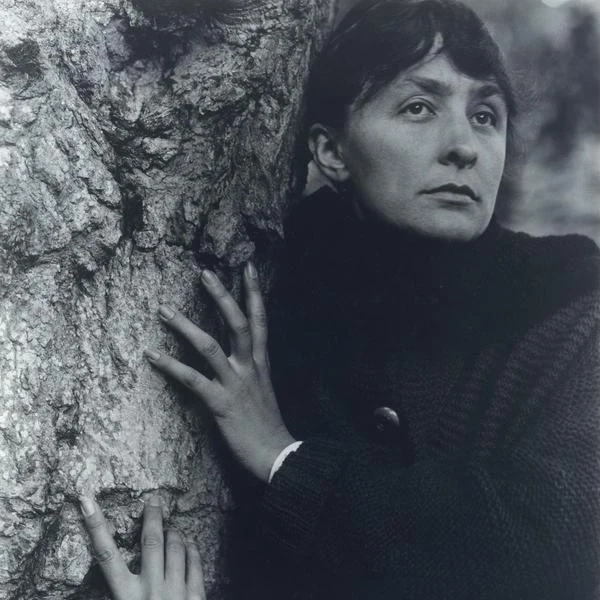

Fig. 1: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills #10, 1978

The Illusion of Identity

Identity is a costume with no one underneath. Cindy Sherman’s entire oeuvre proves this unsettling truth—not through theory, but by embodiment. For over forty years, critics have erred in calling her photographs self-portraits. ‘’I never see myself in these images,’’ Sherman confessed in a 1990 New York Times profile, ‘’they’re excavations of something else entirely.’’ (Kimmelman, n.d., as cited in The New York Times)[1]

The Pictures Generation and Postmodern Critique

Cindy Sherman has probed the construction of identity, playing with the visual and cultural codes of art, celebrity, gender, and photography. As a central figure of the Pictures Generation-alongside Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, and Robert Longo. Sherman responded to the mass media landscape of the 1970s by appropriating and critiquing its imagery with subversive.[2] Her work, particularly Untitled Film Stills (1977–1980), destabilizes the boundaries between originality and imitation, a hallmark of postmodern practice. Her Untitled Film Stills aren’t nostalgic homages to cinema; they’re crime scenes where the victim is the ‘real’ woman (see Fig. 1)-a figure dismantled through ‘’deliberately ambiguous narratives that imitate Hollywood’s production shots.’’ (Hauser & Wirth, 2022)

Femininity as Masquerade in Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980)

De Beauvoir’s Foundation: Gender as Construct

Cindy Sherman's seminal series Untitled Film Stills constitutes a profound visual investigation of femininity as socially constructed performance, engaging in critical dialogue with psychoanalytic and feminist film theories. The work builds upon Simone de Beauvoir's foundational assertion that gender is an acquired rather than innate characteristic, "one is not born, but rather becomes a woman,"(Beauvoir, 2011, p. 283)[3]

Form and Technique: Subverting Cinematic Tropes

Cindy Sherman's groundbreaking Untitled Film Stills comprises seventy black-and-white photographs that revolutionized contemporary photography's relationship with identity, gender, and representation. This iconic series, created when Sherman was just 23 years old, mimics the visual language of 1950s-60s Hollywood, film noir, B movies, and European art-house cinema while deliberately subverting their narratives.[4] What began as experiments in Sherman's apartment eventually expanded to urban and rural locations, requiring assistants to help capture the precisely staged scenes.[5]

Lacan’s Gaze and the Fractured Self

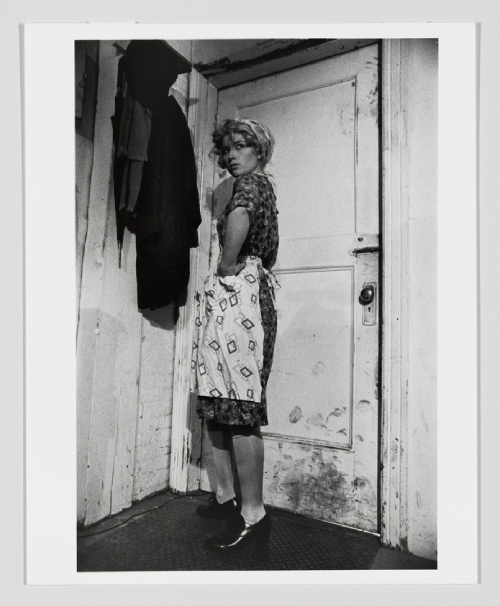

Fig. 2: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #7, 1978

The photographs engage fundamentally with Jacques Lacan's psychoanalytic theory of the gaze, which posits vision as a site of alienation: the subject becomes both viewer and viewed, trapped in what Lacan called the "mirror stage’s" misrecognition. Sherman literalizes this split by embodying stereotypical female roles; the ingénue, the housewife, the femme fatale (Fig. 2), while denying any stable "self" behind them.[6]

Riviere’s Masquerade Theory Embodied

Sherman's work gives visual form to Joan Riviere's 1929 psychoanalytic concept of femininity as defensive masquerade. Riviere's case study of an accomplished professional woman who performed exaggerated femininity to mitigate her "masculine" intellectual success demonstrates how womanhood operates as cultural performance rather than essential quality. As Riviere famously observed, "womanliness could be assumed and worn as a mask," a formulation Sherman literalizes through her serial self-transformations. The photographs confirm Stephen Heath's interpretation that "authentic womanliness is such a mimicry, is the masquerade" - there exists no original femininity behind the performance.[7]

Hal Foster’s Critical Perspective on Cindy Sherman’s Work

Fig. 3: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills # 2, 1977

Foster positions Sherman within 1970s New York’s artistic milieu, where she emerged alongside peers like Sherrie Levine and Barbara Kruger as part of the "Pictures Generation"– artists critically engaging with mass media’s visual language.[8] His analysis reveals three key dimensions of her practice:

1. The Gaze and Performed Identity

Foster observes Sherman’s unique ability to capture "the female subject under the gaze" while simultaneously exposing the psychological mechanisms behind self-presentation. He notes her subjects "see, of course, but they are much more seen," emphasizing how her work dramatizes the tension between active looking and passive objectification. This duality manifests most powerfully in moments of "psychological estrangement," as seen in Untitled Film Still #2 (1977), (Fig. 3) where the distance between a woman and her mirrored reflection reveals what Foster calls "the gap between the imagined and actual body-images."(Foster, 2012)

2. From Cinematic Tropes to Cultural Critique

Foster traces Sherman’s evolution from early experiments with gender performativity (1975-82) through her later grotesque phases (1983-90s), arguing her work constitutes "an epitome of the death of the author."(Foster, 2012) He particularly emphasizes how her 2000s Hollywood/Hamptons series critiques ageism and class anxiety through portraits of "nouveau-riche ladies...stretched to the point where the cracks surface."(Foster, 2012)

3. Biographical Allegory

Contrary to early readings of Sherman’s work as anti-biographical, Foster identifies a subtle personal narrative: "the arc of her subjects from ingénue to dame is not unlike that of her own life."(Foster, 2012) He frames this as a generational allegory, where Sherman’s artistic evolution mirrors how "the postmodernist generation...had that future hijacked by a reactionary turn."(Foster, 2012).

Mulvey’s Male Gaze and Sherman’s Subversion

Laura Mulvey's groundbreaking 1975 essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" provides a crucial framework for understanding Sherman's intervention. Mulvey's analysis of classical Hollywood cinema's "male gaze" reveals three interlocking perspectives that objectify women: the camera's gaze, the male characters' gaze, and the audience's gaze. Sherman replicates these visual structures while systematically exposing their artificiality. The photographs exemplify Mulvey's observation that in patriarchal visual culture, women exist as "to-be-looked-at-ness," their appearance coded for maximum erotic impact while remaining narratively passive.[9]

Anticipating Butler and Irigaray: Gender as Performance

The series anticipates later feminist theorists like Judith Butler and Luce Irigaray. Butler's notion of gender as performative iteration finds visual precedent in Sherman's work, particularly her demonstration that identity emerges through repetitive citation of cultural codes. She claims that “gender ontology is reducible to the play of appearance.” (Butler, 1999, p. 47)[10] Irigaray's concept of woman as "enveloped in the needs/desires/fantasies of others" manifests in Sherman's careful reconstruction of media-derived female types.[11]

Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills: Deconstructing Identity Through Cinematic Masquerade

Fig. 4: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills # 21, 1978

Ultimately, Untitled Film Stills transcends artistic achievement to function as theoretical discourse. The series materializes complex psychoanalytic and feminist concepts about gender construction, demonstrating how visual culture produces and naturalizes feminine identity. Sherman's photographs don't merely depict women - they reveal Woman as cultural fiction, showing how identity forms through perpetual masquerade within patriarchal systems of representation.

Each carefully constructed image functions as an enigma. Untitled Film Still #21 (see Fig. 4) exemplifies Sherman's approach: a woman in vintage 1950s attire gazes anxiously beyond the frame, evoking suspense about an unseen narrative. As MoMA notes, these works "recall the film stills used to promote movies" while remaining intentionally ambiguous, inviting viewers to project their own interpretations. (MoMA, n.d.) This calculated ambiguity transforms Sherman's photographs from mere images into psychological provocations - they're less about what's shown than about the cultural baggage viewers bring to them.

Sherman's process reveals her radical approach to identity construction. As she famously stated: "I wish I could treat every day as Halloween, and get dressed up and go out into the world as some eccentric character" (MoMA, n.d.). In the Film Stills, she single-handedly embodied every role-not just as model, but as photographer, director, costume designer, and stylist.[12] Sherman depicts: “When I prepare each character I have to consider what I’m working against; that people are going to look under the make-up and wigs for that common denominator, the recognizable. I’m trying to make other people recognize something of themselves rather than me.” (Schulz-Hoffman, 1991, p. 30)[13]

Fig. 5: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills # 35, 1979

Through wigs, makeup, and thrift-store costumes, Sherman transformed into archetypes: the jaded seductress, the unhappy housewife (Fig. 5), the vulnerable ingénue. What is hidden behind this farce is only a “fractured being (is) defined by a phallic lack.” (Heartney, 2007, p. 173)[14] These weren't characters but cultural caricatures "invented characters and scenarios [that] imitated the style of production shots."(Hauser & Wirth, 2022) The resulting images expose how mass media, particularly cinema, reduces female identity to reproducible tropes.

Performing Gender: Judith Butler’s Drag Theory and Cindy Sherman’s Subversive Repetitions

1. Drag as Revelatory Framework in Sherman’s Film Stills

Judith Butler’s conceptualization of "drag" as an exposé of gender’s performative foundations provides a critical lens for analyzing Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977–1980). Butler’s assertion that gender constitutes a "stylized repetition of acts" within rigid social frameworks is materially realized in Sherman’s serial embodiment of cinematic archetypes-the ingénue, the femme fatale, the suburban housewife.

Each photograph stages what Butler terms a "failed repetition" (Butler, 1991, p. 24), wherein Sherman’s exaggerated performances (e.g., conspicuously artificial wigs, melodramatic poses) parallel drag’s capacity to reveal gender’s artifice. Untitled Film Still #21 (see Fig. 4) exemplifies this: while adopting film noir’s "spider woman" trope, Sherman amplifies its theatricality through harsh lighting and fragmented composition, denaturalizing the very femininity it appears to depict. Sherman’s deliberate exposure of performative mechanics-visible makeup seams, conspicuously staged settings-corresponds to Butler’s contention that heterosexuality must continually repeat itself to sustain the "illusion of its own uniformity."[15] Both artists-theorists demonstrate how such repetitions inevitably falter, exposing gender’s constructed core.

Fig. 6: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills # 3, 1977

2. The Paradox of Agency and Constraint

Butler’s caution against conflating performativity with individual agency proves essential to understanding Sherman’s oeuvre. While her self-portraits ostensibly assert creative control (as photographer, model, and art director), they simultaneously underscore gender’s discursive boundaries. As Lebovici observes, Sherman’s work, like Claude Cahun’s, employs "theatrical costumes and improvised backdrops" to frame gender as masquerade.[16] Yet Sherman’s reliance on Hollywood’s visual lexicon-such as the infantilized secretary in Untitled Film Still #3 (Fig. 6, 1977) confirms Butler’s argument that subversion occurs within historically conditioned systems.

Technical Evolution and Expanded Narratives

The series' technical evolution mirrors its conceptual depth. Sherman initially worked in her apartment, using domestic spaces to heighten the tension between private and performed selves. Later locations-urban alleys, rural highways - became backdrops for "disguise and theatricality, mystery and voyeurism, melancholy and vulnerability." (Artlead, 2022) This geographical expansion paralleled Sherman's growing sophistication in manipulating cinematic conventions: dramatic lighting, voyeuristic angles, and carefully crafted "moments" that suggested larger, nonexistent narratives. Sherman's subsequent series developed these ideas further. The Rear Screen Projections (1980) abandoned real locations for studio setups using projected backgrounds, a technique borrowed from Alfred Hitchcock. (Hauser & Wirth, 2022) This transition marked Sherman's move from parodying specific film genres to interrogating the very apparatus of image production. The controversial Centerfolds (1981) took this further, appropriating the visual language of men's magazine centerfolds to expose, "the way we consume images - especially of women."(Hauser & Wirth, 2022). Commissioned then censored by Artforum, these works demonstrated how Sherman's "feminist art" made the establishment uncomfortable by holding up a mirror to its voyeurism.

A Legacy of Provocation

From Film Stills to Centerfolds, Sherman’s work revolutionized photography by collapsing the roles of artist, subject, and critic. As MoMA asserts, she "opened the door for generations to rethink photography as a medium." (MoMA, n.d.) Her enduring influence lies in this paradox: by embodying cultural clichés, she revealed their emptiness-yet left unresolved whether her art liberates or entraps the female image. Sherman’s work is not about revealing identity but about its endless fabrication. In an era of social media and digital avatars, her exploration of selfhood as mutable and mediated feels more urgent than ever. Whether read as feminist critique, postmodern pastiche, Sherman’s photographs compel us to confront the fictions we inhabit. She "revolutionized the role of the camera in artistic practice," transforming it from a documentary tool into an instrument of cultural critique. (Hauser & Wirth, 2022) The Film Stills don't just depict women; they reveal Woman as a cultural fiction, endlessly reproduced but never real.

Essay by malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1.Kimmelman, Michael. (1990) 'A Portraitist’s Romp Through Art History', The New York Times [online], 1 February. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

2. Museum of Modern Art (n.d.) Cindy Sherman [artist profile]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

3. Beauvoir, Simon e. de (2011) The Second Sex. Translated by C. Borde and S. Malovany-Chevallier. New York: Vintage, p. 283.

4. Hauser & Wirth (2022) Cindy Sherman 1977–1982 [exhibition text]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

5. Artlead (2022) 'Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills', Artlead Journal [online]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

6. Curating the Contemporary (2014) 'Subverting the Male Gaze: Femininity as Masquerade in Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980) by Cindy Sherman' [blog], 7 November. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

7. Ibid.

8. Foster, Hal. (2012) 'At MoMA', London Review of Books [online], 34(9). (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

9. Curating the Contemporary (2014) 'Subverting the Male Gaze: Femininity as Masquerade in Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980) by Cindy Sherman' [blog], 7 November. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

10.Butler, Judith. (1999) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, p. 47.

11.Curating the Contemporary (2014) 'Subverting the Male Gaze: Femininity as Masquerade in Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980) by Cindy Sherman' [blog], 7 November. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

12.Artlead (2022) 'Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills', Artlead Journal [online]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

13.Schulz-Hoffmann, Carla and Sherman, Cindy (1991) Cindy Sherman: Untitled Film Stills. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, p.30.

14.Heartney, Eleanor (2007) After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art. Munich: Prestel, p.173.

15.Butler, Judith. 1991. Imitation and gender insubordination. In Inside/Outside: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, edited by Diana Fuss. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 13-31.

16.Lebovichi, Elisabeth. 1995. "I am in training don't kiss me." In Claude Cabun Photographe, edited by Francois Leperlier. Paris: Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, pp. 17-21.

Image Sources:

Cover Image:

Arthead (2022) Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills, Arthead Journal [online]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

Fig. 1: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills #10, 1978.

Arthead (2022) Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills, Arthead Journal [online]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

Fig. 2: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #7, 1978.

Museum of Modern Art (n.d.) Cindy Sherman [artist profile]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

Fig. 3: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills #2, 1977.

Museum of Modern Art (n.d.) Cindy Sherman [artist profile]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

Fig. 4: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills #21, 1978.

Arthead (2022) Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills, Arthead Journal [online]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

Fig. 5: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills #35, 1979.

Whitney Museum of American Art (n.d.) Collection: Cindy Sherman. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

Fig. 6: Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Stills #3, 1977.

Arthead (2022) Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills, Arthead Journal [online]. (Accessed: 5 June 2025).