The Resurgence of Minimalist Art in 2024

From Radical Movement to Cultural Necessity

In an era defined by digital overload, environmental crises, and relentless consumerism, minimalist art has emerged as both an aesthetic refuge and a philosophical antidote.[1] What began in 1960s New York as a radical rejection of Abstract Expressionism's emotional excess has evolved into one of the most vital and commercially successful art movements of our time.[2] The 2024 art market tells a compelling story; minimalist works by Donald Judd command $20 million at auction, digital minimalist NFTs sell for hundreds of thousands in cryptocurrency[3] and major corporations from Apple to Google build their brands on minimalist principles. This isn't just a revival, it's a cultural reckoning with the very meaning of value in art and design.[4]

Minimalism is exemplified by the idea of "less is more" as first coined by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. This approach involves stripping a design down to its bare essentials, casting aside any elements that do not contribute to the pure beauty or function of an object or space.[5] The minimalist movement emerged in the 1960s as a direct challenge to the dominant Abstract Expressionist paradigm. Where Jackson Pollock splattered emotion across canvases and Mark Rothko enveloped viewers in color fields, artists like Donald Judd, Agnes Martin, and Carl Andre pursued something radically different: art that existed as literal presence rather than symbolic representation.[6]

Judd's precisely fabricated metal boxes, Flavin's arrangements of commercial fluorescent lights, and Andre's grids of industrial bricks weren't meant to express inner turmoil or metaphysical yearning.[7] They were investigations of form, space, and materiality what Judd called "specific objects" that existed somewhere between painting and sculpture. This was art that demanded physical engagement rather than psychological interpretation, where the viewer's experience of moving around a Judd stack or walking across an Andre floor piece became part of the work itself. Judd also tried to explain that what he called "the new work" was in no way minimal, reductive, "anti-art," "ABC art," or any of the other words and phrases (e.g., "Primary Structures") invented to suggest extreme simplicity.[8]

The 2024 Minimalist Art Market: A Comprehensive Analysis of What's Selling

In 2024, minimalist art has emerged as one of the most commercially successful and culturally relevant art movements. While maintaining its core principles of reduction, geometric precision, and material honesty, minimalism has expanded to include surprising new practitioners and formats. This analysis examines the full spectrum of minimalist art sales, from classic works to contemporary interpretations, while maintaining focus on the movement's essential characteristics.[9]

The Blue-Chip Minimalist Market

The foundation of 2024's minimalist market remains the established masters. Donald Judd's 1980 aluminum stack achieved $20.1 million at Christie's (fig. 1), with complete wall-mounted progressions commanding $15-18 million and smaller wall boxes trading at $3-5 million. Agnes Martin's 1977 Untitled 5 grid sold for $12 million at Sotheby's (fig. 2), while her early 1960s graphite works reach $8-10 million and later pastel-hued paintings stabilize at $6-8 million. Carl Andre's 37 Pieces of Work in magnesium brought $7.6 million (fig. 3), with copper floor pieces maintaining $5-7 million valuations. Market analysts note these artists maintain 10-15% annual appreciation, with particularly strong demand for works from the 1960s-70s.[10]

Fig 1: Donald Judd, Untitled (1980): The Paradox of Permanent Aluminum

Fig 2: Agnes Martin’s Minimalist Masterpiece: Untitled 5 (1977), Pencil and Acrylic Grid

Fig 3: Carl Andre’s Metallic Grid: 37 Pieces of Work (1969), Magnesium Floor Installation

Minimalism's Unexpected Practitioners

The minimalist movement has found surprising champions in artists not typically associated with the genre. Yayoi Kusama's 1959 painting No. F fetched $8.2 million at Sotheby's, while her white Infinity Net series reached $10.5 million in private sales, with demand surging 40% since 2020 (fig. 4). Banksy's Love is in the Bin sold for $23.7 million, his Flower Thrower murals trade for $6-8 million (fig. 5), and Mobile Lovers achieved $4.2 million privately. These artists demonstrate how minimalism's influence transcends traditional boundaries.[11]

Fig 4: Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Nets (1958–60), acrylic on canvas

Fig 5: Banksy’s Flower Thrower (2003/5): The Ephemeral Trade of Protest Art

Digital and Sustainable Minimalism

In the NFT space, Rafał Rozendaal's single-color animations command 220 ETH ($660K), while Dmitri Cherniak's algorithmic Ringers series averages 85 ETH. The digital minimalist market shows 65% year-over-year growth. Simultaneously, Eva Berendes' fabric-and-steel wall reliefs ($45-75K) and Tomás Saraceno's biodegradable installations ($250-500K) command 20-30% premiums over conventional works, signaling strong collector demand for sustainable art.[12]

Emerging Minimalist Artists

Alicja Kwade's steel/stone conceptual works ($300-600K), Ann Veronica Janssens' light installations ($150-400K), Josiah McElheny's glass sculptures ($80-250K), and Tauba Auerbach's geometric paintings ($150-300K) demonstrate how contemporary practitioners expand minimalism's boundaries while maintaining its core principles.[13]

Market Dynamics and Future Outlook

Recent trends show a 40% surge in primary market inquiries at leading galleries, while auction houses introduce dedicated minimalist sales. Online platforms report 65% growth in sub-$50K transactions. Collector motivations center on visual longevity, spatial versatility, and conceptual engagement. Projections indicate continued 10-15% annual price growth and increased museum acquisitions.[14]

The Enduring Power of Reduction

From Judd's industrial precision to Banksy's street simplicity, from Kusama's early experiments to cutting-edge digital works, minimalism continues evolving while retaining its core philosophy. As MoMA prepares its 2025 survey, the movement confirms that in our complex world, the power of reduction remains more valuable than ever.[15]

Essay by malihe Norouzi / Independent Aer Scholar

References

1. Madavi (2024) Minimalistic design: the hottest trend in 2024. Available at: https://madavi.co/minimalistic-design-the-hottest-trend-in-2024/ (Accessed: 25 March 2025).

2. Chave, Anna. C. (2008) 'Revaluing minimalism: patronage, aura, and place', The Art Bulletin, 90(3), pp. 466-486. (Accessed: 15 September 2017).

3. BuyWallArt (2024) What art is selling in 2024. (Accessed: [28 March 2025).

4. Madavi (2024) Minimalistic design: the hottest trend in 2024. (Accessed: 25 March 2025).

5. Interior Architects (no date) When less is more or less is a bore. (Accessed: 25 March 2025).

6. Chave, Anna. C. (2008) 'Revaluing minimalism: patronage, aura, and place', The Art Bulletin, 90(3), pp. 466-486. (Accessed: 15 September 2017).

7. Ibid.

8. Wilkin, Karen. (2014) 'Perfect unlikeness: Donald Judd as critic', Artforum, 52(8). (27 March 2025).

9. BuyWallArt (2024) What art is selling in 2024. (Accessed: [28 March 2025).

10. Madavi (2024) Minimalistic design: the hottest trend in 2024. (Accessed: 25 March 2025).

11. BuyWallArt (2024) What art is selling in 2024. (Accessed: [28 March 2025).

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

Image Credits:

Fig 1: Donald Judd, Untitled (1980): The Paradox of Permanent Aluminum. (Accessed: 26 March 2025)

Fig 2: Agnes Martin’s Minimalist Masterpiece: Untitled 5 (1977), Pencil and Acrylic Grid. (Accessed: 26 March 2025)

Fig 3: Carl Andre’s Metallic Grid: 37 Pieces of Work (1969), Magnesium Floor Installation. (Accessed: 26 March 2025)

Fig 4: Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Nets (1958–60), acrylic on canvas. (Accessed: 26 March 2025)

Fig 5: Banksy’s Flower Thrower (2003/5): The Ephemeral Trade of Protest Art. (Accessed: 26 March 2025)

Navigating the Evolving Art Market: From Traditional Valuations to Digital Disruptions

The art market has long been a unique intersection of creativity, culture, and commerce, evolving from a system of patronage to a globalized, speculative ecosystem. Historically, artists relied on patrons, and their works were created for cultural or religious purposes, far removed from the speculative investment landscape that defines much of the art market today. Over time, however, art has shifted from a purely cultural artifact to an asset class with considerable financial value. This transition from patronage to institutionalized commerce, further fueled by technological innovation, has created a complex and often opaque market. The art market’s intricate valuation process involves subjective factors like artistic merit and reputation. It also relies on objective elements, such as auction records and economic trends. Today, the market is driven by a combination of historical legacies, economic dynamics, and new digital technologies. As the market has evolved, so have the tools and frameworks used to evaluate and buy art. In this article, we explore the factors influencing art valuation, trace the historical transformation of the art market, and examine how technology is shaping the future of art pricing.[1]

Fig. 1: Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses.

The Complex Dynamics of Art Valuation

The price of artwork is determined by a combination of tangible and intangible factors, many of which are rooted in both the subjective tastes of buyers and the broader economic landscape. Art valuation is a delicate balancing act between an artist’s reputation, the rarity of the work, its provenance, and broader market conditions. These factors combine in a way that can make the pricing of art seem both highly speculative and uncertain.2 As Chloe Waddington, partner at London-born gallery Timothy Taylor, explains, “No single factor should be considered in isolation or as more important than another. Valuing an artwork is a combination of many factors: institutional recognition, market demand, career stage of the artist, condition, authenticity, medium ...” (Artsy, n.d.) This holistic approach to valuation highlights the intricate interplay of elements that contribute to an artwork’s market value.[3]

Artist Reputation and Career Stage

One of the most influential factors in determining the price of a piece of art is the reputation of the artist. An artist's career stage, institutional recognition, exhibitions, and personal achievements all elevate an artwork's market value. Emerging artists may start with lower prices, but as they gain exposure through solo shows, biennial exhibitions, or critical acclaim their works become more valuable. The works of well-established artists with significant historical or cultural relevance often fetch premium prices, especially if they have been exhibited in prestigious institutions or sold through renowned auction houses.[4]

In the secondary market, the valuation of an artist’s work is influenced by auction results, which serve as public price benchmarks. Auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s track these prices, giving buyers and collectors a concrete understanding of the financial value of an artwork. As collectors and investors, understanding these market benchmarks is key. Auction records, especially for "blue-chip" artists, often influence the pricing of lesser-known works in the same genre or style.[5]

The Role of Provenance

Provenance, or the history of an artwork’s ownership, is another crucial element in determining its value. A well-documented provenance can confirm the authenticity of the work, ensuring it is not a forgery or stolen property. Works with prestigious provenance such as those previously owned by famous collectors, shown in renowned exhibitions, or featured in historical contexts often carry significantly higher prices.[6]

The concept of provenance is particularly vital in the secondary market, where resold works often come with a verified history. For example, a painting that has been owned by a celebrity or has been part of a notable museum collection tends to have a higher price tag. Sotheby’s and other auction houses frequently emphasize the importance of "fresh-to-market" works pieces that have not been publicly offered for sale before and therefore lack a bidding history. These works can trigger bidding wars due to their rarity and their provenances, which add layers of desirability.[7]

Supply, Demand, and Market Dynamics

Like any other asset class, the law of supply and demand plays a pivotal role in the art market. Limited supply, particularly in the case of artists who produce only a small number of works, can significantly drive up the price of a given piece. For example, Banksy, a globally renowned street artist, is known for creating limited edition works that often originate as street art. According to MyArtBroker, Banksy’s pieces have achieved record-breaking prices at auction, reflecting the high demand for his scarce and culturally significant works. For instance, his painting Devolved Parliament sold for £9.9 million at Sotheby’s in 2019, far exceeding its pre-sale estimate. Similarly, his iconic Girl with Balloon made headlines when it partially self-destructed immediately after being sold for £1.04 million, further highlighting the unique appeal and value of his limited works. On the other hand, the oversupply of works, particularly by less-established artists or overproduced art in a saturated market, can depress prices.[8]

Fig. 2: Banksy, Girl with Balloon, Waterloo Bridge, South Bank, London, 2002.

The global economic climate also influences the art market. Art has long been seen as a store of value, especially during times of economic uncertainty. In a time of financial crisis or inflation, art, like gold or real estate, can act as a hedge against economic instability. The 2008 financial crisis, for example, saw art prices plummet briefly, but the market rebounded quickly as the rich saw art as a more stable investment than volatile financial markets.[9]

Historical Transformation of the Art Market

Understanding the evolution of the art market is essential to grasping its present state. Historically, artists operated within a system of patronage, relying on wealthy individuals or institutions for financial support. From the great commissions of Renaissance artists like Michelangelo to the portraiture of the 18th century, the relationship between artist and patron was one of mutual benefit—artists created works of cultural significance, and patrons secured status and prestige. The 20th century, however, saw the art market’s transformation into a globalized, speculative ecosystem. This shift was catalyzed by the rise of auction houses, galleries, and art dealers who began shaping the commercial value of art. The establishment of major auction houses like Sotheby’s (1744) and Christie’s (1766) allowed art to be traded publicly, which added transparency and a new level of speculation to the market. By the mid-20th century, the market was becoming more institutionalized, as art was increasingly treated as an asset class, with buyers seeking not only aesthetic value but also financial returns.[10]

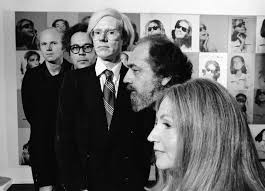

One of the most significant moments in this shift occurred in the 1960s with the rise of Pop Art. King of Pop Andy Warhol operated his art practice like a business, creating works inspired by the popular commercial products of his age, and churning out screen prints like a business. Warhol named his New York studio the ‘Factory’, and employed assistants here to help him produce more and more sellable art for ever-growing prices. He challenged traditional notions of art by merging mass production with fine art. Warhol’s famous quote: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.”(Warhol, 1975, p.92) Highlighted the commercialization of art and its potential as a lucrative investment. This new wave of art, with its connection to branding and popular culture, signaled the beginning of art as a commodity.[11]

The 1970s and 1980s further accelerated this transformation, with the rise of art as an investment vehicle. The Scull Auction in 1973, in which the taxi magnates Robert and Ethel Scull sold a collection of Pop Art works for $2.2 million, demonstrated the vast potential of the market. The 1980s saw the emergence of art collectors as financial investors, with individuals and institutions turning to art as a viable alternative asset class.[12]

Fig. 3: Collectors Ethel and Robert Scull with Andy Warhol, George Segal and James Rehnquist, 1973.

The Digital Disruption of the Art Market

As the art market has evolved, so too has the role of technology. Today, digital platforms are reshaping how art is bought and sold, allowing for greater accessibility and transparency. Platforms like Artsy, Artnet, and Paddle8 have made the art market more democratic, enabling collectors to browse works from around the world without ever stepping into a gallery. Online auctions have become increasingly popular, with houses like Christie’s and Sotheby’s leading the charge in selling works digitally. Blockchain technology has also introduced new ways to secure provenance and establish transparency. Artory, for example, uses blockchain to track the ownership history of artworks, ensuring that each transaction is verifiable and immutable. This technology addresses one of the long-standing issues in the art market: the lack of transparency. By using blockchain, buyers can rest assured that the provenance of a piece is legitimate and that it is not the subject of any legal disputes.[13]

Another major disruption to the art market has been the rise of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). In 2021, digital artist Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days sold for a staggering $69 million at Christie’s, marking the first time a major auction house had sold a purely digital work. NFTs, which use block chain technology to authenticate and verify ownership of digital art, have introduced an entirely new way to buy, sell, and collect art. However, the rise of NFTs has sparked debate over the environmental impact of blockchain technology, with critics pointing out that minting NFTs consumes significant amounts of energy. The growing prominence of digital art and NFTs raises questions about the future of traditional art forms. While NFTs and digital platforms democratize access to the market, they also create new challenges in terms of sustainability, ethical considerations, and market volatility. The future of the art market will likely be a blend of traditional institutions and innovative technologies, with both sectors coexisting to create new opportunities for artists, collectors, and investors.[14]

The Future of the Art Market: Democratization vs. Exclusivity

One of the most pressing debates in the art market today is the tension between democratization and exclusivity. Digital platforms have undeniably broadened access, enabling new collectors to engage with works from emerging artists and global markets. Social media platforms like Instagram have amplified the visibility of artists who might otherwise have remained obscure. Yet, despite these advancements, the art market remains heavily concentrated in the hands of a select few. According to the Art Basel & UBS Report, 85% of auction revenue is generated by the top 1% of artists, with high-net-worth collectors continuing to dominate the high-end market.[15]

This concentration of wealth raises critical questions about accessibility and equity in the art world. While digital platforms have opened doors for younger and less affluent collectors, high-value works remain largely inaccessible to the majority. The growing perception of art as a financial asset, rather than a cultural or creative pursuit, has only deepened these disparities. As the art market evolves, it will be shaped by the interplay of tradition and innovation. Whether the market moves toward greater inclusivity or entrenches its exclusivity will depend on how artists, collectors, and institutions navigate these forces. The art world stands at a crossroads, and its trajectory will ultimately reflect the values and priorities of those who shape it.[16]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

Refrences:

1. ArtRow. n.d. How Pricing and Valuation Work on the Art Market. [Accessed 15 October 2023].

2. Ibid.

3. Artsy. n.d. What Determines the Price of an Artwork? [Accessed 10 October 2023].

4. MyArtBroker. n.d. Concise History of the Art Market. [Accessed mid-October 2023].

5. ArtRow. n.d. How Pricing and Valuation Work on the Art Market. [Accessed 15 October 2023].

6. Artsy. n.d. What Determines the Price of an Artwork? [Accessed 10 October 2023].

7. MyArtBroker. n.d. Concise History of the Art Market. [Accessed mid-October 2023].

8. MyArtBroker. n.d. Banksy Record Prices. [Accessed early October 2023].

9. ArtRow. n.d. How Pricing and Valuation Work on the Art Market. [Accessed 15 October 2023].

10. MyArtBroker. n.d. Concise History of the Art Market. [Accessed mid-October 2023].

11. Warhol, Andy. 1975. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). New York: Harcourt, pp. 87–95.

12. MyArtBroker. n.d. Banksy Record Prices. [Accessed early October 2023].

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. McAndrew, C. 2020. The Art Market 2020. Art Basel & UBS Report. [Accessed 15 October 2023].

16. MyArtBroker. n.d. Banksy Record Prices. [Accessed early October 2023].

Images and Cover Image Sources:

1. Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

2. Banksy (2002) Girl with Balloon [Graffiti]. (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

3. Warhol, A. (1973) Mao [Screenprint on paper]. (Accessed: 20 July 2024).