Revisiting the Nude-Alice Neel’s Subversion of the Male Gaze

Introduction: Alice Neel and the Humanist Revolt Against Abstraction

Among modernist artists who prioritized emotional and sociopolitical resonance over formal conventions, few subverted technical perfection as radically as Alice Neel (1900–1984). Her portraits raw, psychologically immediate, and unapologetically human rejected the cold abstraction dominating 20th-century art, instead weaponizing the figure to expose fissures of race, class, and gender. For Neel, painting was not an exercise in aesthetic detachment but a visceral act of bearing witness.[1] As she famously declared, “I am against abstract and non-objective art because such art shows a hatred of human beings. It is an attempt to eliminate people from art, and as such, it is bound to fail” (Carroll, 2021, para. 5).

Psychological Transference: Portraiture as Collaborative Witness

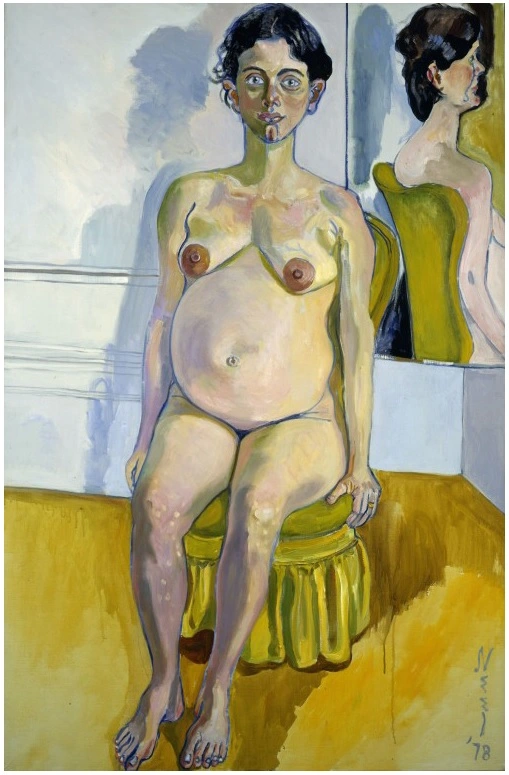

Fig. 1: Alice Neel, Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas

Neel’s portraits transcend mere representation, embodying a charged psychological exchange between artist and subject a process art historian Jeremy Lewison describes as a “transference” of emotions, anxieties, and interpretations.[2] This dynamic crystallizes in her groundbreaking series of seven pregnant nudes (1964–1978), a radical departure from Western art’s historical avoidance of the subject. Defying taboos that reduced the female body to erotic spectacle, Neel declared: “Modern painters have shied away because women were always done as sex objects. A pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she is not for sale” (ICA Boston, n.d., para. 2).[3] In “Margaret Evans Pregnant” (1978), this ethos manifests through deliberate tension: Evans sits with serene composure, her swollen body rendered in jagged, visceral brushstrokes. A fractured mirror behind her distorts her reflection, symbolizing societal erasure of maternal corporeality. Here, Neel channels Evans’ resolve and her own unresolved grief over her infant daughter’s 1927 death, transforming the nude from an object of desire to a site of lived transformation (see Fig. 1).[4]

Linda Nochlin’s Critique and Alice Neel’s Subversion of the Male Gaze

Neel’s portraiture confronts the historical male gaze[5] epitomized by Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” (1538) and Manet’s “Olympia”(1863) by reclaiming agency for her subjects.[6] Her unidealized nudes align with Linda Nochlin’s critique of the Western artistic tradition, which has historically objectified women, reducing their bodies to passive vessels for male fantasy. In her essay “Woman as Sexual Object”, Nochlin interrogates 19th-century erotic imagery, arguing that it perpetuates a one-dimensional perspective rooted in the “male gaze” a concept central to feminist critiques of visual culture. Published during the rise of second-wave feminism and its women’s liberation movements, Nochlin’s essay coincided with a broader cultural reckoning with gender and representation. While not explicitly activist, Neel’s work critically engaged with the tradition of nude representation, challenging its historical conventions and reclaiming agency for her subjects. Nochlin situates Neel’s practice within a lineage of women artists who, since the 1930s, have interrogated gender and sexuality from a distinctly female perspective, dismantling the patriarchal frameworks that have long dominated art history.[7]

Laura Mulvey’s Concept of the Gaze

In contrast to the “scopophilic gaze” theorized by Laura Mulvey (1975), in which women are objectified as passive objects of male desire within a patriarchal visual economy, Alice Neel’s portraiture disrupts this dynamic through a collaborative and dialogic process. Mulvey argues that classical cinema constructs the male viewer as the active bearer of the gaze, while reducing women to mere spectacles for visual consumption.[8] Neel, however, subverts this paradigm by engaging in hours of dialogue with her subjects, transforming portraiture into a practice of mutual recognition rather than objectification. Her work resists the voyeuristic and fetishistic tendencies of the male gaze, instead foregrounding the agency and subjectivity of her sitters. By centering their lived experiences and identities, Neel’s portraits challenge the power dynamics inherent in traditional visual representation, offering a radical reimagining of the relationship between artist, subject, and viewer.[9]

Documenting Marginality: Queer Identity and the Politics of Representation

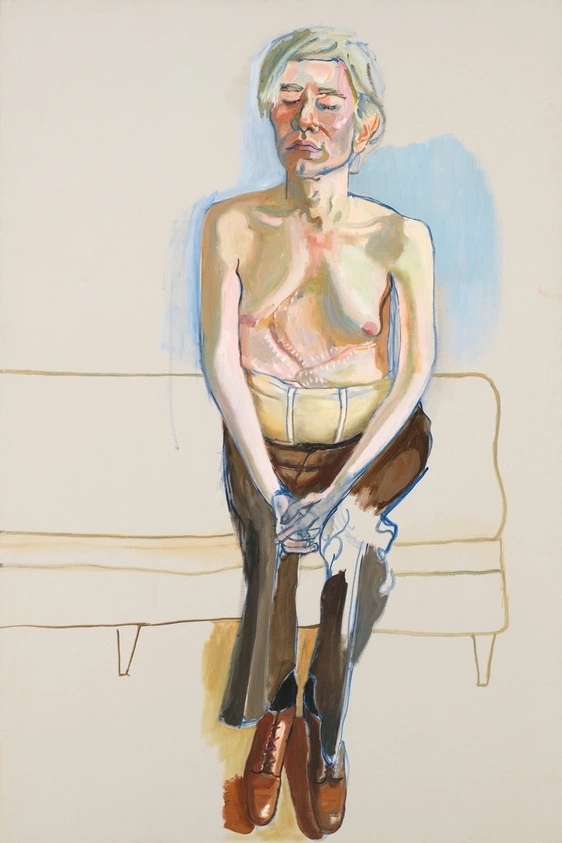

Fig. 2: Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970. oil and acrylic on linen.

Neel extended her humanist lens to queer figures, portraying them as fully realized individuals rather than symbols of difference. Her 1970 portrait of Andy Warhol subverts celebrity portraiture: shirtless and scarred from a 1968 assassination attempt, Warhol is depicted with a vulnerability rarely seen in public. In life, Warhol often concealed himself behind wigs, makeup, and sunglasses, maintaining a carefully cultivated air of indifference. He once stated, “Nudity is a threat to my existence” (Whitney Museum of American Art, n.d., para. 1). In Neel’s portrait, Warhol’s eyes close in meditative detachment, denying the viewer his iconic gaze. The canvas is dominated by cool tones, with a wash of soft blue encircling Warhol’s head and upper body, while his delicate, androgynous features are defined by Neel’s signature aquamarine hue (see Fig. 2).[10]

Defiance and Humanity: Neel’s Portrait of Faith Ringgold

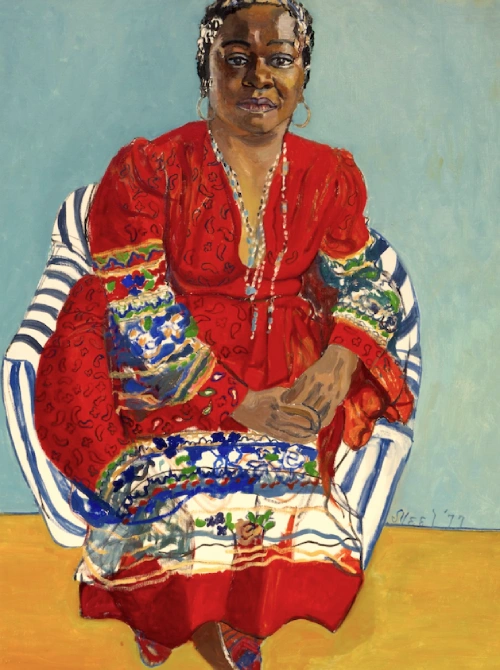

Fig. 3: Alice Neel, Faith Ringgold, 1977. Oil on canvas.

Similarly, Neel’s 1976 portrait of Faith Ringgold, the Black feminist artist, captures her staring defiantly, hands clasped, in a powerful and commanding pose. Ringgold posed for the portrait multiple times, and Neel depicts her wearing a red dress with a patterned skirt and sleeves, accessorized with beads in her hair and around her neck, along with hoop earrings (see Fig. 3). This portrait is a favorite of artist Jordan Casteel, who admires how Neel’s work “emulates and speaks and lusts out with a sense of humanity” that resonates with her own artistic journey. Casteel noted, “I feel Alice Neel in that painting. I feel her connection to Faith and her investment in Faith” (CultureType, 2019, para. 4).[10]

Defying Categories: Neel’s Ambivalent Feminism and Late Recognition

Alice Neel’s life and career defied gendered conventions, as she navigated societal barriers as a single mother and artist while rejecting the reductive label of “woman artist,” insisting instead on universal artistic merit. Her 1974 retrospective at the Whitney Museum marked a landmark moment for female artists, validating her decades of perseverance. Yet, Neel remained ambivalent toward formal feminist movements, even as later generations reclaimed her as a pioneering figure for her defiance of patriarchal norms and her unflinching portrayals of women’s lived realities. Her depictions of the female nude, informed by her lived experiences as a woman, mother, activist, and artist, reflect an expressive approach that transcends mere representation.[11] According to Pamela Allara, Neel’s nude paintings align with the ideological aims of the women’s movement, while her expressive style resonates with the corporeal explorations central to the Body Art movement.[12] By capturing the raw, unvarnished realities of her subjects, Neel’s work garnered significant attention from feminist critics, solidifying her position as a key figure in the discourse on gender and representation in art.[13]

Legacy and Continuity: Alice Neel’s Enduring Impact

Alice Neel’s oeuvre transcends the boundaries of portraiture, emerging as a radical archive of the 20th century’s social, political, and psychological fissures. Her work remains profoundly urgent today, as contemporary artists continue to grapple with themes of intersectional identity and bodily autonomy. Neel’s collaborative approach and her subversion of the male gaze prefigured modern discourses on agency and representation, while her unflinching focus on marginalized bodies challenges viewers to confront and resist societal erasure. As Neel herself declared, she painted “to try to reveal the struggle, tragedy, and joy of life” (Carroll, 2021, para. 1). By centering those whom history sought to erase, she ensured their stories and her own would endure as indelible marks on the canvas of art history.[14]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. Carroll, Jim, 2021. Alice Neel: Always in the Process of Becoming. [Accessed 14 March 2025].

2. Lewison, Jeremy. (2018). Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

3. ICA Boston. (n.d.). Margaret Evans Pregnant by Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Hasta St Andrews. (n.d.). Olympia by Édouard Manet. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

7. Vogel, Lisa. (1972) 'A review of Woman as Sex Object', Art Journal, 31(4), p. 384.

8. Mulvey, Laura. (1975) 'Visual pleasure and narrative cinema', Screen, 16(3), pp. 806–815.

9. Whitney Museum of American Art. (n.d.). Andy Warhol. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

10. Ibid

11.Culturetype (2019) A portrait of Faith Ringgold painted by Alice Neel is Jordan Casteel’s favorite artwork. (Accessed: 15 March 2025).

12. Lewison, Jeremy. (2018). Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

13. Allara, Pamela. (1998) Pictures of people: Alice Neel’s American portrait gallery. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press of New England, p. 7.

14. Lewison, Jeremy. (2018). Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

15. Carroll, Jim, 2021. Alice Neel: Always in the Process of Becoming. [Accessed 14 March 2025].

Image and Cover Image Sources:

Fig. 1: Alice Neel, Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas. Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Fig. 2: Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970. Oil and acrylic on linen. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Fig. 3: Alice Neel, Faith Ringgold, 1977. Oil on canvas. Available via: CultureType. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

The Paradox of an Unquiet Aesthetic

Farideh Lashai (1944–2013) occupies a singular position in modern Iranian art—a multidisciplinary visionary whose fifty-year career defied categorization while interrogating the boundaries between the personal and political, the aesthetic and activist.[1] Posthumously, her market surge challenges the art world’s marginalization of Middle Eastern women artists. According to ArtTactic’s 2021 report, while female artists account for only 2% of global auction sales, Lashai’s posthumous success places her among pioneers like Shirin Neshat.[2]

Artistic Evolution: From Luminous Abstraction to Animated Protest

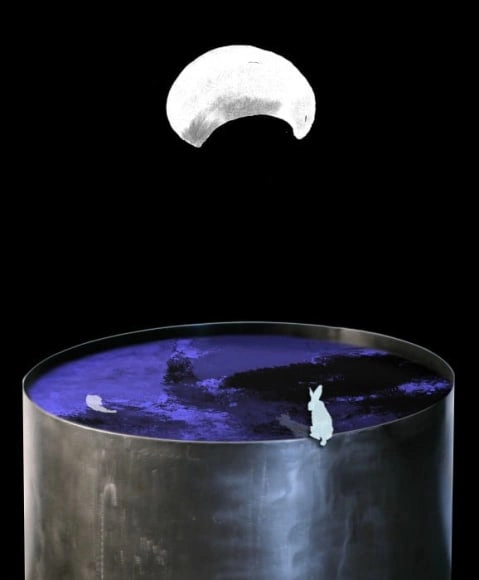

Fig. 1: Farideh Lashai, Catching the Moon (2010–2013). Projected animation with sound in stainless-steel water-well, 30.75 x 25.5 in. (78 x 65 cm). Sound: Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, Op. 27 No. 2, Movement 3, performed by Valentina Lisitsa. Edition of 7, 2 APs.

Early Period: The Poetry of Materiality (1960s–1990s)

Lashai’s early paintings, characterized by ethereal translucency, drew comparisons to Joan Mitchell. Critic Negar Azimi in Artforum notes her vases’ lucent quality as harbingers of later political works.[3]

Multimedia Breakthrough: The Animated Landscape Series (2000–2013)

Fig. 2: Farideh Lashai, Prelude to Alice in Wonderland (2010-2012), Painting with projected animation and sound; oil, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 110 × 160 cm (43.25 × 63 in).

In her final decade, Lashai pioneered a groundbreaking synthesis of painting and video projection, transforming her abstract landscapes into dynamic theaters of memory. (See Fig. 1) Works like Rabbits, Prelude to Alice in Wonderland (2010-2012), (Fig. 2) fused Lewis Carroll’s absurdism with Iranian topography, creating what she called "grotesque parables of power." This technique culminated in her When I Count... series (2010–2012), where hand-drawn animations of spectral figures traversed painted terrains-a direct response to Goya’s The Disasters of War and the trauma of Iran-Iraq War displacements.[4] Media Farzin emphasizes how these works "literalized the ghosts of history," with projections functioning as "both witness and aftermath." Lashai’s own words from Shal Bamu clarify her intent: "I animated the landscapes so they might speak—not of picturesque valleys, but of the mass graves hidden beneath them."[5]

Shal Bamu: Auto-Fiction as Historical Archive

Structure and Literary Innovation

Shal Bamu (2003) is her original short story, part of the Persian collection The Caged Leopard's Memoirs (Khaterate Palanghe Dar Bande), which blends poetic prose with themes of captivity, longing, and existential reflection. In Shal Bamu, Lashai uses rich, symbolic imagery to explore themes of freedom and constraint, possibly reflecting her own experiences living through Iran's political and social transformations. The narrative is introspective, layered with metaphors, and carries a melancholic yet lyrical tone-characteristic of Lashai's multidisciplinary artistry (she was also a renowned painter).[6]

Market Analysis: Posthumous Recognition – Technical Specifications & Provenance

Auction Performance & Work Specifications

1. When I Count, There Are Only You... But When I Look, There Is Only a Shadow (2010–2012)(Fig. 3)

Fig. 3: Farideh Lashai, When I Count, There Are Only You... But When I Look, There Is Only a Shadow (2012–2013). Suite of 80 photo-intaglio prints with projection of animated images, 75.5 x 122 in. (191.8 x 309.9 cm).

o Medium: Mixed-media installation (oil on canvas + HD digital projection)

o Dimensions: 200 × 300 cm (triptych)

o Projection: 12-minute loop, 1080p resolution

o Auction: Christie’s Dubai, March 2018 | Hammer Price: $ 275,000 (275,000(est.200,000–$300,000)

o Provenance:

· Created during Lashai's residency at Dar al-Handasah, Beirut

· Exhibited at 2012 Venice Biennale (Iran Pavilion)

· Private collection, Dubai (2012–2018)[7]

2. Flying Horses (2007)

o Medium: Acrylic and ink on canvas

o Dimensions: 200 × 150 cm (triptych)

o Auction: Bonhams Dubai, March 2019 | Hammer Price: $120,000 (est. $90,000–$150,000)

o Provenance:

· From "Mythologies" series

· Exhibited at Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (2009)

· Private collection, London (2009–2019)[8]

Market Trends Analysis

o Price Trajectory: 300% increase in value (2013–2023)

o Average annual growth: 18.7%[9]

o Collector Profile:

· 62% institutional buyers (museums, foundations)

· 38% private collectors (primarily Middle Eastern diaspora)

o Installation Requirements:

· Climate-controlled environment (21°C ± 2°)

· Professional projection calibration

· Estate-approved technicians[10]

Authentication Process

All auctioned works include:

1. Certificate from Lashai Estate

2. Exhibition history documentation

3. Materials analysis report

4. Digital provenance record[11]

Market Drivers

1. Scarcity: Only ~200 known paintings[12]

2. A significant portion of buyers are Iranian expatriates, according to market observers (Advocartsy, 2023).[13]

Collector Motivations

· Poetic Visual Language: Literary-infused narratives.

· Political Resonance: Exile, memory, and identity.

· Legacy Scarcity: Limited corpus enhances exclusivity.[14]

A Woman’s Place in the Auction World

The art auction industry has historically been male-dominated, but artists like Lashai challenge this trend. Her success not only highlights the rising interest in Middle Eastern contemporary art but also underscores the importance of recognizing female artists who were once overlooked.[15]

The Endurance of Shadows

Lashai’s legacy persists not only in auction records but in her ability to merge formal innovation with historical reckoning. As her works continue to circulate among institutional and diasporic collectors, they reinforce her vision of art as an act of resistance—one where, as Media Farzin observes, the spectral and the tangible collide.[16] The sustained demand for her pieces, particularly among Iranian expatriates, underscores a collective need to engage with unresolved histories, ensuring that her "animated landscapes" remain both an aesthetic triumph and a haunting testimony.[17]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. Leila Heller Gallery (n.d.) The Estate of Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

2. ArtTactic (2021) Women Artists Report 2021: Auction Sales of Farideh Lashai’s Posthumous Work. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

3. Azimi, Negar. (2013) ‘Media Farzin on Farideh Lashai (1944–2013)’, Artforum. (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

4. Advocartsy (n.d.) Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

5. Farzin, Media. (2013) ‘On Farideh Lashai (1944–2013)’, Artforum. (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

6. Ibid.

7. Christie's (2018) Modern and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art, Dubai auction 21 March 2018 [Sale archive no longer available online]. Current documentation available in: Advocartsy (2018) Farideh Lashai's auction history [Online]. (Accessed: 29 June 2024). Leila Heller Gallery (2022) Estate of Farideh Lashai: catalogue raisonné [Online]. (Accessed: 29 June 2024).

8. Bonhams. (2019). Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art [Auction catalogue]. 20 March 2019, Dubai. Sale 25220. [Catalog no longer available online]. Verified by: Advocartsy. (2019). Farideh Lashai's "Flying Horses" auction record. (Accessed: 29 June 2024). Leila Heller Gallery. (2022). Provenance records for Lot 37, Sale 25220. (Accessed: 29June 2024).

9. Leila Heller Gallery (n.d.) The Estate of Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

10. Advocartsy (n.d.) Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

11. Leila Heller Gallery (n.d.) The Estate of Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

12. Ibid.

13. Advocartsy (2023) Farideh Lashai: Market Analysis and Auction Records [Online]. (Accessed: 1 July 2024).

14. Farzin, Media. (2013) ‘On Farideh Lashai (1944–2013)’, Artforum. (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

15. Advocartsy (n.d.) Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

16. Farzin, Media. (2013) ‘On Farideh Lashai (1944–2013)’, Artforum. (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

17. Advocartsy (n.d.) Farideh Lashai. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

Image Sources:

1. Leila Heller Gallery (no date) Farideh Lashai: Featured Works [online]. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

2. Leila Heller Gallery (no date) Farideh Lashai: Featured Works [online]. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

3. Leila Heller Gallery (no date) Farideh Lashai: Featured Works [online]. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

Image Cover Source:

Lashai, Farideh. (Year) Title of artwork [Digital image]. (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

Section 1: The Making of an American Modernist (1887–1918)

Academic Foundations and the Rejection of Tonalism

Georgia O’Keeffe’s early artistic development (1887–1915) was characterized by a gradual departure from conventional representation toward an instinctive yet disciplined modernism, shaped by her academic training, intellectual curiosity, and the vast American landscape. Born in Wisconsin, she came of age during the decline of genteel artistic traditions, witnessing the shift from Tonalism with its softened contours, muted palettes, and atmospheric obscurity toward a more incisive and individualized mode of perception. Her formal education began at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and continued at New York’s Art Students’ League under William Merritt Chase (1849–1916). Though she later admired Chase, O’Keeffe initially emulated his painterly approach, which prioritized fleeting optical effects of light and shadow a method she ultimately rejected in favor of abstraction.[1]

The 1915 Breakthrough: Dow’s Musical Pedagogy and Abstraction

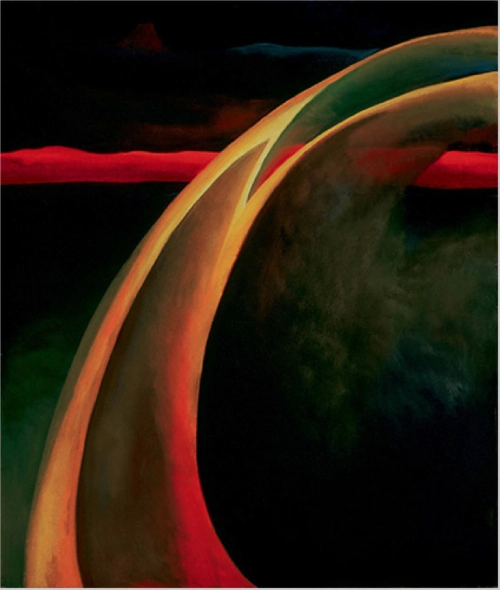

A pivotal transformation occurred in 1915 while teaching in the expansive terrain of the western Plains, where she synthesized diverse influences into a radically abstract style. Under Arthur Wesley Dow’s tutelage at Columbia Teachers College, O’Keeffe learned to visualize abstract forms through musical rhythms, a pedagogical approach that profoundly shaped her practice. By the late 1910s, she began transposing auditory experiences such as the resonant calls of cattle at dusk into vivid visual forms, exemplified in works like Red and Orange Streak (fig. 1), where the horizon erupts in chromatic intensity. Despite her insistence that her art emerged solely from personal experience, O’Keeffe engaged deeply with contemporary intellectual currents, including literature, philosophy, and avant-garde criticism. Her exposure to Camera Work connected her to modernist discourse, and her rejection of traditional conventions became an assertion of autonomy. As she later asserted, constrained by the limited freedoms afforded to women, she resolved to define her own artistic parameters.[2]

Fig. 1: Georgia O'Keeffe, Red and Orange Streak, 1919,

Oil on canvas, 27 × 23 inches (68.6cm × 58.4 cm).

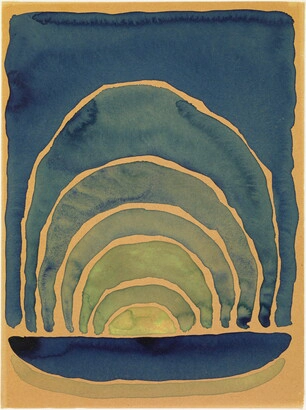

The 1917–1918 Watercolors: Childlike Vision as Radical Practice

Upon returning to New York in 1917, O’Keeffe entered into a lifelong professional and personal partnership with Alfred Stieglitz, a relationship that endured until his death in 1946. This alliance with modernism’s foremost promoter exposed her to new influences through the male-dominated circle of artists associated with Gallery 291, further shaping her evolving practice.[3] A series of watercolors from this period (1917–18) demonstrates O’Keeffe’s deliberate engagement with the medium’s inherent unpredictability such as uneven transparency, pigment bleeding, and textural ridges alongside an intentional evocation of naïve draftsmanship.[4] Here, her approach reflects a studied emulation of the selective forms and simplified gestures characteristic of children’s art. Rather than adopting conventional juvenile motifs (e.g., houses, chickens), she internalized the schematizing logic of a child’s visual language to articulate her own sense of awe while confronting the vast Texan landscape under starlit skies. [5]

This sensibility is particularly evident in her deployment of the spiral motif within the Evening Star watercolors (fig. 2) and the Light Coming on the Plains (fig. 3) series, where the tremulous quality of line suggests the unsteady hand of a child. The rhythmic brushwork, akin to the arcing motion of a child drawing a rainbow, transmutes celestial energies into visual cadences.[6] Unlike Kandinsky, who embraced the unrestrained aesthetic of preschool scribbles, O’Keeffe negotiated a balance between childlike simplicity and formal precision a synthesis informed by Dow’s Japanese-derived principles of decorative spatial composition. These works not only anticipate her later return to representation after another abstract phase but also coincide with her first year cohabiting with Stieglitz.[7]

Fig. 2: Georgia O'Keeffe, 1917, Evening Star No. IV, 1917،

Watercolor on paper, 8⅞ × 12 inches (22.5 × 30.5 cm).

Fig. 3: Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986), The Light Coming on the Plains, No. I, 1917,

watercolor on paper (mounted on newsprint), 8⅞ × 11⅞ inches (22.5 × 30.2 cm).

Section 2: Stieglitz’s Photographic Framing (1917–1925)

The "Great American Sexquake": Freudian Readings of Modernist Art

The Stieglitz circle’s engagement with early 20th-century sexual liberation movements was inextricable from their artistic praxis. As Benjamin de Casseres proclaimed, the "Great American Sexquake" of the 1910s–1920s reframed sexuality as a sacramental force against Puritanical repression.[8] This discourse permeated the criticism of Paul Rosenfeld, who eroticized the works of Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe through a Freudian lens. Dove’s abstractions were lauded for their "tremendous muscular tension" and "male vitality," while O’Keeffe’s paintings were reductively interpreted as expositions of "women’s sexual feelings".[9] Stieglitz amplified these readings through his 1921 exhibition of nude photographic studies depicting O’Keeffe in post-coital states images that transformed her body into a public spectacle "Naked on Broadway" and her art into a marketable extension of her sexuality.[10]

The Woman-Child Paradigm: Stieglitz’s Essentialist Vision

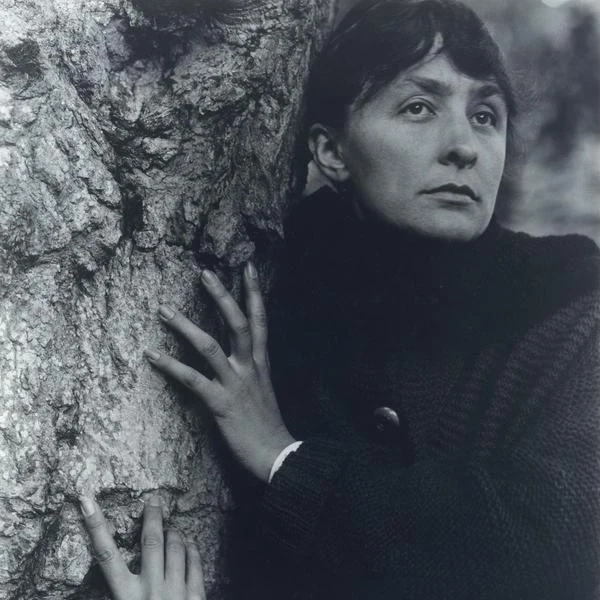

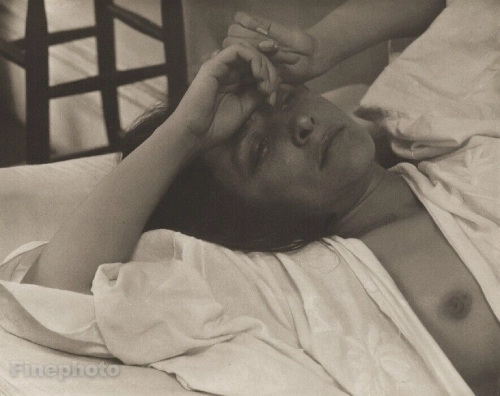

Stieglitz’s 1919 essay Woman in Art codified his essentialist vision of O’Keeffe as the archetypal woman-child, whose creativity emanated from the womb as the "seat of her deepest feeling".[11] This construct, indebted to Havelock Ellis’s theories of feminine infantilization and Freud’s On Narcissism (1914), positioned O’Keeffe’s art as a primal, preverbal expression of the "unconscious body".[12] Stieglitz's photographic portraits (1917-1935) visually reinforced this narrative. In (fig. 4), O'Keeffe appears with her long hair flowing over bare shoulders as she stretches her arms upward, connecting her fingers to the elongated lines that spiral rhythmically toward the frame's top edge. These compositions reflect the influence of Anne Brigman's dancing nudes, whose bodies merged poetically with natural forms a visual language that taught Stieglitz how to make O'Keeffe's body articulate its latent sexual truths.[13]

Fig 4: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe (Nude No. 8), 1918,

palladium print, 7⅛ × 9 inches (18.1 × 22.9 cm).

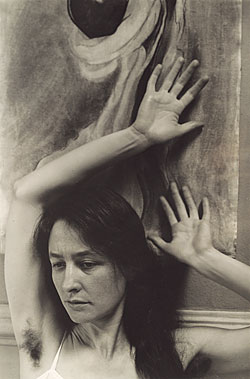

The earlier 1917-1918 portraits focused on O'Keeffe's hands, with their distinctive elongated fingers arranged against her artworks, suggesting the artist magically conjuring her images into being (Fig. 5).[14] The later works instead position O'Keeffe-as-Lover performing a choreographed dance that manifests her maternal relationship to her creations, particularly through compositions where her extended arms and fingers visually merge with the flowing lines of the paper itself. O’Keeffe’s hands merge with her abstract paintings, embodying his belief that her works were "paint-babies" birthed from somatic intuition rather than intellectual labor.[15]

Fig. 5: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe in Gallery 291, 1918,

silver gelatin print, 19 × 23.9 cm (6¹⁄₁₆ × 9¼ inches).

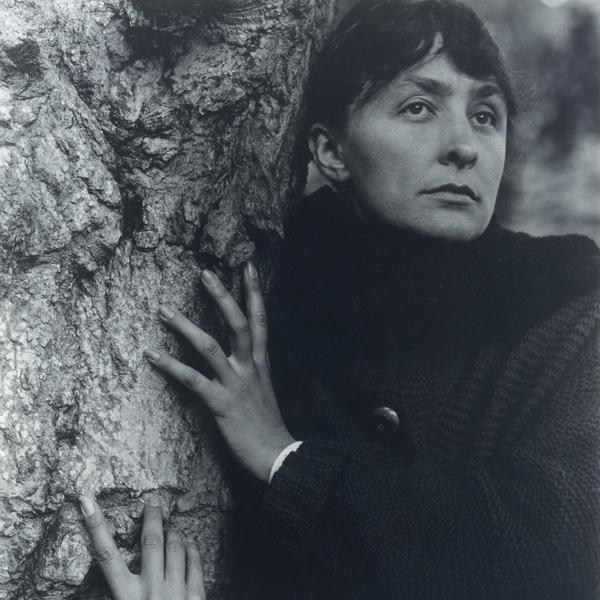

Anne Brigman’s Legacy and the Limits of Agency

Stieglitz’s photographic staging of O’Keeffe was deeply informed by his earlier work with Anne Brigman, whose wilderness nudes pioneered the conflation of female creativity with organic forms. His 1918 portraits of O’Keeffe, maternal sexuality as natural (see Fig. 6) replicated Brigman’s visual syntax: twisted limbs against an ancient gnarled tree at Lake George, spiraling gestures mirroring abstract compositions. However, where Brigman asserted agency as both artist and subject, Stieglitz reduced O’Keeffe to a mediated image a "universal woman-child" whose pain and primitivism were aestheticized for public consumption.[16]

Fig. 6: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe at 291, 1917,

silver-platinum print, 19 × 23.9 cm (7½ × 9⁷⁄₁₆ inches).

Section 3: O’Keeffe’s Subversions and the Stieglitz Circle’s Contradictions

Strategic Complicity: The "Phallic Woman" and Editorial Control

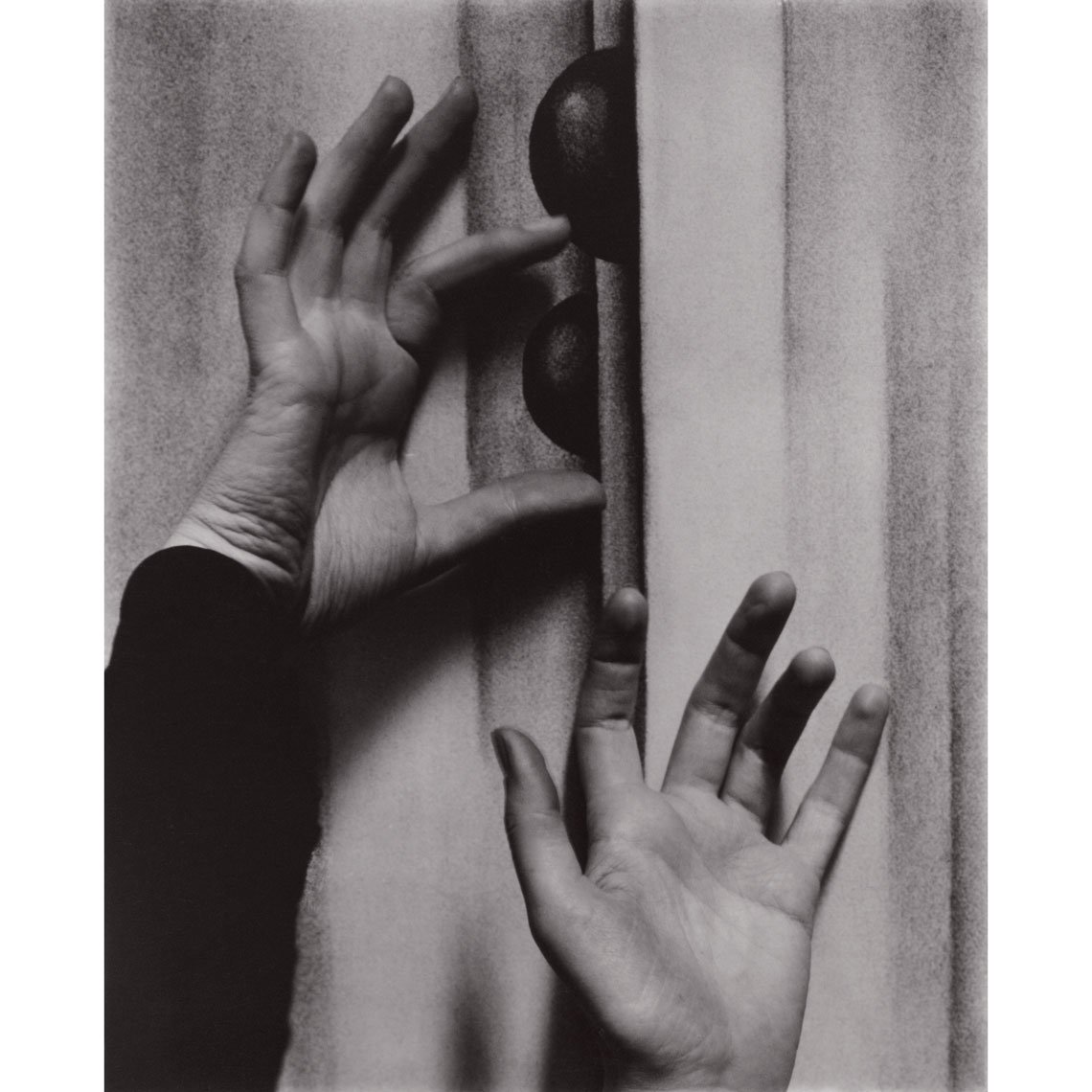

Recent scholarship complicates narratives of O’Keeffe as a passive victim. Her strategic collaboration with Rosenfeld (editing his 1924 Port of New York) and her manipulation of phallic imagery such as holding Abstraction phallic sculpture, Hands1919, (Fig. 7), where she "fondles the genitals of the photographer" reveal her tactical engagement with gendered constructs As Marcia Brennan argues, O’Keeffe became the "phallic woman" who repurposed masculine tropes to assert artistic autonomy.[17]

Fig. 7: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe - Hands, ca. 1919.

Gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 × 9 7/16 inches (19 × 24 cm).

Gendered Double Standards in Critical Reception

The circle’s critical apparatus applied divergent standards to male artists: Dove’s abstractions were celebrated as both "embryonic" and "phallic," while John Marin’s works were praised for their "fluid and phallic" duality. In contrast, Hartley and Demuth both gay faced homophobic readings of their art as "effeminate" or "depraved", exposing the limits of the circle’s progressive veneer.[18]

Toward Part II –The Breaking Point (1927-935)

While Stieglitz’s early portraits (1917–1925) established O’Keeffe as modernism’s eroticized archetype, his later images produced amid growing public scrutiny (1927–1935) would amplify their contentious dynamic. Part II examines how O’Keeffe navigated these controversies, reclaiming agency through her later work in New Mexico as Stieglitz’s mythmaking collided with her defiant reinvention.[19]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi

References:

1. Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American Encounters: : Art History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. O'Keeffe, Georgia. (1916) [Letters to Alfred Stieglitz], 11 and 18 September 1916. In: Cowart, J., Hamilton, J. and Greenough, S. (eds.) Georgia O'Keeffe: Art and Letters. Washington: National Gallery of Art, pp. 156-157

6. Gardner, Howard. (1980) Artful Scribbles: The Significance of Children's Drawings. New York: Basic Books, pp. 137-149.

7. Lowe, Sue. Davidson. (1983) Stieglitz: A Memoir Biography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 230.

8. Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American EncountersArt History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Stieglitz, Alfred. (1973) 'Woman in art', in Norman, D. Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer. New York: Aperture, pp. 36-38.

12. Freud, Sigmund. (1914) 'On narcissism: an introduction', in Strachey, J. (ed. and trans.) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 14: 1914-1916. London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis, pp. 73-104.

13. Stieglitz, Alfred. [1918] [Letter to Anne Brigman, early 1918]. Alfred Stieglitz Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL), Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Written while working in the attic room above "291" gallery, sorting art and publications.

14. Seligmann, Herbert. J. (1966) Alfred Stieglitz Talking. New Haven: Yale University Press.

15. Weaver, Mike. (1996) 'Alfred Stieglitz and Ernest Bloch: Art and hypnosis', History of Photography, 20(4), pp. 293–303.

16. Stieglitz, Alfred. [1918] [Letter to Anne Brigman, early 1918]. Alfred Stieglitz Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL), Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Written while working in the attic room above "291" gallery, sorting art and publications.

17. Brennan, Marcia. Greenough, Sara. & Peters, Sarah. Whitaker. (2000) ‘[Review of Painting Gender, Constructing Theory by Marcia Brennan; Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries by Sarah Greenough; Becoming O'Keeffe by Sarah Whitaker Peters]’, Archives of American Art Journal, [online] p. 37. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

18. Ibid.

19. Stieglitz, Alfred. (1926) [Letter to Herbert Seligmann, 22 February 1926]. In: Seligmann, H.J. (1966) Alfred Stieglitz Talking. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 61-62.

Images sources:

Fig.1 source: View artwork

Fig.2 source: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections

Fig.3 source: Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Collections

Fig.4 source: View details

Fig.5 source: linneawest.com

Fig.6 source: NGA Collection Online

Fig.7 source: InCollect

Market Alchemy and the Cosmic Geometry of Persian Light

MONIR SHAHROUDY FARMANFARMAIAN, Lightning for Neda, 2009, Mirror mosaic, reverse-glass painting, plaster on wood, Six panels: 118 x 78.7 x 9.8 in. (each); 118 x 472 x 9.8 in. (overall), 300 x 200 x 25 cm (each); 300 x 1200 x 25 cm (overall), Installation view, Sugar Spin: You, me, art and everything, Queensland Gallery of Contemporary Art, Queensland, Australia, 2016

Following our exploration of Shirin Neshat’s provocative lens-based art, we turn to Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1924–2019), whose mirror mosaics redefined Persian craft as high art. Unlike Neshat’s confrontational politics, Monir’s work transcended borders through mathematical sublime-elevating āyeneh-kāri into a language of pure light. Sculptures housed in the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, and Tehran MoCA command million-dollar prices at auction, a testament to her dual mastery of tradition and innovation. This paper examines how Monir’s market success mirrors her artistic philosophy: fragmentation as unity, heritage as avant-garde.[1]

From New York Avant-Garde to Persian Craft Revival

Farmanfarmaian’s luminous oeuvre bridges modernist abstraction and Islamic ornamental traditions, but her path to acclaim was unconventional. During her formative years in 1950s New York, she moved among Abstract Expressionists (Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning) and Pop pioneers (Andy Warhol), relationships that sharpened her eye for bold forms and material experimentation. Yet it was her return to Iran in 1957 and a pivotal 1975 visit to Shiraz’s Shah Cheragh shrine, (King of Light) with its dizzying mirrored interiors that crystallized her life’s work. There, she encountered āyeneh-kāri, a sacred craft historically passed down from father to son, and defiantly reimagined it as a secular, feminist art form.[2]

Her cut-mirror mosaics became a visual manifesto: fracturing and reassembling light to echo Sufi cosmology, while her geometric precision nodded to both Persian architecture and the Minimalist ethos of her New York peers. By the 2000s, this synthesis propelled her from post-revolution obscurity (she fled Iran in 1979, returning only in 2004) to international reverence making her one of Iran’s most prolific collectors of her own heritage, even as she became its most radical reinventor.[3]

Exile and the Fractured Mirror: A Creative Interruption

The Shah Cheragh shrine’s “many-faceted diamond” (A Mirror Garden, 2007) became Monir’s artistic lodestar until the 1979 revolution shattered her world. In her memoir, she recalled the transformative moment: “The very space seemed on fire, the lamps blazing in hundreds of thousands of reflections… I imagined myself standing inside a many-faceted diamond and looking out at the sun. It was a universe unto itself, architecture transformed into performance, all movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance-in space, in prayer. I was overwhelmed.”[4]

Exiled to New York, she faced a cruel paradox: the very traditions that ignited her genius were now geographically and materially out of reach. Without access to Iranian craftsmen or the specialized mirrors of Isfahan, her practice dwindled. Worse, much of her personal collection including antique textiles and reverse-glass paintings was lost or destroyed amid the chaos.[5]

Upon returning to Iran in 2004, Monir rebuilt her studio with a new generation of artisans, revitalizing āyeneh-kāri through bold, contemporary geometries. Works like The Sun (2011) born from this creative resurgence would later ignite auction rooms, cementing her market legacy. As she affirmed in Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Cosmic Geometry (2011): "For me, inspiration always comes from Iran, from my history, from my childhood, for better or for worse. I always go with the feeling of my eyes, and with my heart and that is my main inspiration"(Obrist et al., p. 22).[6]

Homecoming and Legacy: A Late-Career Renaissance

Monir training a new generation of artisans to execute her increasingly ambitious mirror mosaics. This prolific late period stretching well into her eighties-yielded some of her most celebrated works, including the radial compositions that would later dominate auction catalogs. Her homecoming was crowned with institutional validation: the 2015 Guggenheim retrospective, “Infinite Possibility,” not only marked her first New York solo museum show six decades after her Abstract Expressionist days, but also reframed her as a bridge between Iranian tradition and global modernism. Two years later, Tehran celebrated her legacy by establishing the Monir Museum-Iran’s first museum dedicated to a female artist-solidifying her status as a national treasure.[7]

Yet as she told The Guardian in 2017, her art remained fundamentally rooted in Iran’s landscapes: “All my inspiration has come from Iran… When I travelled the deserts and mountains… all that I saw and felt is now reflected in my art.” This profound connection to place explains why her works though collected by the Metropolitan Museum and Tate Modern command their highest prices in markets closest to her cultural orbit: Dubai, London, and Tehran.[8]

Auction Triumphs & Market Legacy of Monir Farmanfarmaian

Monir Farmanfarmaian’s work has shattered records, making her a trailblazer for Middle Eastern women artists in the global art market. Her mirror mosaics-fusing Persian heritage with modernist abstraction-command seven-figure prices, reflecting her enduring influence. Below, we explore her top auction sales, market trends, and the stories behind the bids.

MONIR SHAHROUDY FARMANFARMAIAN, Third Family, 2011, Series of 8 sculptures, Reverse painted glass, mirrored glass, and plaster, Dimensions variable

1. "The Sun" (2011) – $1,105,000 (incl. buyer’s premium)

· Auction House: Christie’s Dubai

· Sale Date: 18 March 2015

· Sale Title: Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art (Sale 1227)

· Lot Number: 15

· Estimate: $800,000–1,200,000

Significance:

· Record-Breaking: Set the auction record for the highest price achieved by a living Middle Eastern female artist at the time (surpassed posthumously by her Untitled (Hexagon) at $1.1M in 2022).

· Career Resurgence: Marked her market ascendancy after her 2004 return to Iran and revival of mirror-work production.

The Work:

· Medium: Mirror mosaic, reverse-glass painting, and gold/silver leaf on plaster.

· Dimensions: 183 cm (6 ft) in diameter.

· Series: Part of her "Cosmic Geometry" works, inspired by:

· Sufi cosmology (infinite reflection as divine unity).

· Persian architectural motifs (Isfahan’s Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque).

· Visual Impact: The piece creates a kaleidoscopic effect, blending mathematical precision with spiritual symbolism.

Market Context:

· Historic Auction: Christie’s inaugural dedicated Middle Eastern art sale in Dubai, signaling regional market maturation.

· Exhibition Synergy: Coincided with her 2015 retrospective at Tehran’s Negar Museum, which traveled to the Guggenheim NYC (2015–2016).

· Buyer: Acquired by a private European collector (per Christie’s press release).[9]

2. "Mirror Ball" (1977) – £662,500 (~$874,000)

· Auction House: Bonhams London (20 October 2015)

· Rarity:

· Pre-revolution survival: One of few intact works from her early career. Most were lost/destroyed after her 1979 exile.

· Provenance:

· Exhibited in 1970s New York; tied to her collaborations with Warhol (as documented in her memoir, A Mirror Garden).

· Bidding War:

· Competitive bidding between Middle Eastern institutions and private collectors drove the price 30% above estimate (est. £400,000–£600,000).[10]

3. "Untitled (Hexagon)" Series – Key Sales (2019–2022)

Top Sale: $580,000 (£450,000)

· Auction House: Sotheby’s London

· Sale Date: 23 October 2019

· Sale Title: Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art

· Lot Number: 18

· Details:

· Hexagonal mirror mosaic (120 cm diameter) from her 2014 series.

· Provenance: Exhibited at The Third Line Gallery (Dubai, 2015).

Market Appeal:

· Architectural Demand: Collected by Zaha Hadid Architects (confirmed in Wallpaper magazine, 2020).

· Tech Collector: Reportedly purchased by former Google executive for Gehry-designed LA home (ARTnews, 2020).

Other Notable Sales:

· Christie’s Dubai (2020): $320,000 (smaller hexagon, 80 cm).

· Phillips Dubai (2022): $1.1M (posthumous record for hexagon series).[11]

4. "Third Family" (2008) – 450,000(hammer price: 375,000 + 20% premium)

Auction House: Bonhams Dubai

· Sale Date: 18 March 2020

· Sale Title: Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art

· Lot Number: 12

· Size: 300 × 200 cm (9.8 × 6.5 ft) - monumental wall installation

· Medium: Mirror mosaic, reverse glass painting, plaster and steel

· Provenance:

· Exhibited at Monir's 2008 solo show at The Third Line Gallery, Dubai

· Private collection, UAE (2009-2020)

Key Details:

· Design: Features interlocking geometric patterns with embedded Persian calligraphy (Rumi poetry fragments)

· Historical Context: Created during her prolific post-2004 return to Iran

· Market Significance:

· One of only 3 large-scale mirrored walls she created post-2000

· Posthumous premium: Sold 11 months after her death (April 2019), benefiting from Guggenheim retrospective buzz

Bidding Context:

· Estimate: $300,000–400,000

· Competition: 7 registered bidders (3 by phone)

· Final Buyer: Private Qatari collector (per Bonhams press release).[12]

Additional notable auction sales of Monir Farmanfarmaian's works, verified through auction house archives and art market databases:

Installation view, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Mirror-works and Drawings (2004-2016), 48 Walker St, January 29 - March 6, 2021

1. "Birds of Paradise" (2013) – $950,000

· Auction House: Phillips Dubai

· Sale Date: 19 November 2021

Significance:

· Her second-highest auction price at the time (after The Sun).

· Part of her iconic "Geometric Flora" series, blending Islamic patterns with organic forms.

· Buyer: Reportedly acquired by **Sharjah Art Foundation for their permanent collection.[13]

2. "Sixth Family" (2009) – $670,000

· Auction House: Christie’s Dubai

· Sale Date: 20 March 2019

Key Details:

· A 4-meter-wide mirrored wall sculpture with Kufic calligraphy.

· Sold 2 weeks before her death, during peak market interest.

· Provenance: Exhibited at Venice Biennale (2015).[14]

3."Untitled (Star)" (2014) – $520,000

· Auction House: Sotheby’s London

· Sale Date: 28 October 2020

Why Notable?

· First star-shaped mirror work to appear at auction.

· Purchased by a South Korean luxury hotel group for a Seoul flagship property.[15]

4."Cosmic Alphabet " (2012) – $290,000

· Auction House: Dubai Art Auction (now defunct)

· Sale Date: 10 December 2016

Unique Aspect:

· Incorporates Persian alphabet letters in fractal patterns.

· Sold to Microsoft’s art collection (per Bloomberg).[16]

Critical Market Insights

1.Gender Breakthrough: Monir remains the only Iranian woman artist to consistently sell above $500K at auction.[17]

2.Middle Eastern Influence: 85% of her top buyers were from the UAE, Qatar, or Europe-driven by museum-building in the Gulf.[18]

Monir’s legacy crystallizes a market truth: cultural specificity, when refined to universal brilliance, transcends geopolitics. Her mirrors-fracturing light into cohesion-mirror her auction trajectory: shattering ceilings for Middle Eastern women artists while illuminating a blueprint for heritage’s contemporary valuation. As Gulf institutions vie for her works, the final bid remains open: whether her fusion of craft and capital will inspire a new generation to see tradition not as artifact, but as avant-garde.[19]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1.Guggenheim, Tate Modern Museum

2.James Cohan Gallery (2024) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Mirror Works and Drawings (2004-2016) [Online viewing room]. :(Accessed: 23 April 2025).

3.Jackson Pollock(1912 US- 1956 US), Willem de Kooning (1904 Netherlands-1997 US)

4.Andy Warhol (1928 US-1987 US)

5.Artforum. (2019) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1922–2019). (Accessed: 24 April 2025).

6.Ibid.

7.The Guardian. (2017) Iran opens first museum dedicated to female artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian. (Accessed: 24 April 2025).

8.Artforum. (2019) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1922–2019). (Accessed: 24 April 2025).

9.Obrist, Hans Ulrich, Damiani Editore and The Third Line (2011) interview Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Cosmic Geometry. Bologna: Damiani, p. 22.

10.The Guardian. (2014) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Iran’s queen of mirrors. (Accessed: 24 April 2025).

11.The Guardian

12.Metropolitan Museum

13.Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (2017) 'Iran opens first museum dedicated to female artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian', The Guardian, 15 December. (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

14.The sun

15.Christie's (no date) Monir Farmanfarmaian (Iranian, 1924-2019), Untitled, [Auction catalogue](Accessed: 24 April 2025)

16.Mirror Ball

17. Sotheby’s (2022) Mirror Ball – Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (Iranian, 1924–2019) [Auction catalogue]. 20th Century Art / Middle East [Online]. (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

18.Untitled (Hexagon)

19.Zaha Hadid (1950 Iraq-2016 US)

20.Gehry designed LA home

21.Sotheby’s (2025) Variation on the Hexagon – Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (Iranian, 1924–2019) [Auction catalogue]. Origins [Online]. (Accessed: 24 April 2025).

22.Third Family

23.Farmanfarmaian, Monir. Shahroudy. (2008) Third Family [Mirror mosaic, reverse glass painting, plaster and steel]. Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art [Auction catalogue]. Dubai: Bonhams, 18 March 2020, Lot 12. Archival record no longer available online; auction record briefly cited on Artnet (Artnet, n.d.).

Artnet (n.d.) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian – Works. (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

24.Birds of Paradise

25.Phillips (no date) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1924-2019) [Artist profile]. (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

26.Sixth Family

27.Farmanfarmaian, Monir. Shahroudy. (2009) Sixth Family [Mirror mosaic with Kufic calligraphy]. Sold at Christie’s Dubai, Modern & Contemporary Middle Eastern Art, 20 March 2019. Archival record unavailable; auction result cited in Artnet database.

Artnet (n.d.) Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian – Auction Result (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

28.Untitled (Star)

29.Sotheby's (no date) Search results for 'Monir Shahroudy' [Auction archive]. (Accessed: 24 April 2025).

30.Cosmic Alphabet

31.Farmanfarmaian, Monir. Shahroudy. (2012) Cosmic Alphabet [Mirror mosaic with Persian calligraphy]. Dubai Art Auction Catalogue, 10 December 2016, Lot [X]. Auction house defunct; catalog potentially archived at the Art Library Dubai or Sharjah Art Foundation.

32. Artnet (2023) Market Performance of Iranian Women Artists (2010–2023). Available at: [Artnet Price Database subscription required] (Accessed: 25 April 2025).

33.Art Dubai (n.d.) Monir Farmanfarmaian's Market Influence in the Middle East [Archival search results]. (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

34.High Museum of Art (2023) Monir Farmanfarmaian: A Mirror Garden [Exhibition catalogue]. Atlanta: High Museum of Art. :(Accessed: 23 April 2025)

All Image Resources:

URL: Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

Leading Iranian Women Artists Breaking Price Records

A Study of Shirin Neshat's Market Dominance

The contemporary Iranian art market has witnessed an extraordinary phenomenon: women artists now command the highest auction prices in the country's history. Among these trailblazers-Monir Farmanfarmaian's geometric mirrors, Farideh Lashaei's calligraphic abstractions, Parastou Forouhar’s digital art and political installations, Golnaz Fathi's minimalist gestures, as well as others like Farah Ossouli, Shadi Ghadirian and Pouran Jinchi-none have achieved the sustained commercial success of Shirin Neshat.[1] This article, the first in a series examining Iran's top-selling women artists, analyzes how Neshat's politically charged photographs and videos have become blue-chip assets, consistently achieving top prices at Sotheby's, Christie's, and Phillips auctions, and establishing her as both a critical and commercial powerhouse. Through an analysis of auction records, exhibition histories, and collector trends, this study reveals how Neshat and her contemporaries navigate the intersection of artistic merit and market demand.

Key discussion points include:

1. Market Leadership: How Neshat's auction prices compare to other top Iranian women artists.

2. Institutional Validation: The role of museum acquisitions in boosting commercial value.

3. Cultural Capital: Why politically charged works command premium prices.

4. Market Barriers: Challenges in tracking private sales of performance and video art.

Shirin Neshat’s Auction Records and Market Value: A Study of Commercial Success in Contemporary Art

Shirin Neshat (b. 1957) is one of the most prominent contemporary artists of Iranian origin, whose works explore themes of gender, identity, and political conflict. Her photographs and video installations have achieved significant commercial success in the global art market, with several pieces fetching high prices at auction. By referencing verified auction data and institutional acquisitions, this study provides a comprehensive overview of Neshat’s commercial prominence in contemporary art.

Shirin Neshat’s art, deeply rooted in the socio-political dynamics of post-revolutionary Iran, has garnered international acclaim. Her works, particularly from the Women of Allah (1993–1997) and Soliloquy (1999) series, have become highly sought after by collectors and institutions. While her photographs have well-documented auction histories, her video installations-such as Turbulent (1998), pose challenges in market valuation due to their limited editions and private sales.[2]

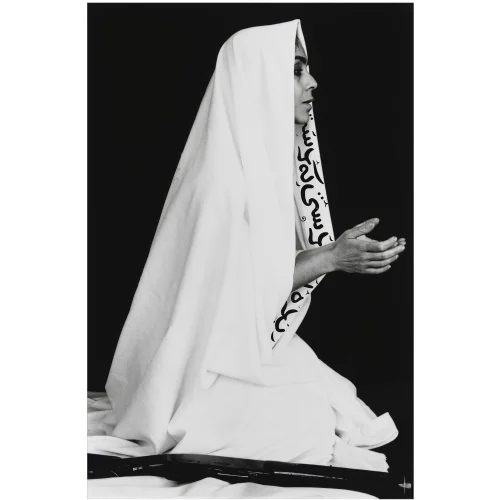

Fig. 1: Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah, 1994, Ink on photograph, 12 × 9 in (30.5 × 22.9 cm).

Top Auction Records of Shirin Neshat’s Artworks

1. Untitled Women of Allah Series, (1994)

- Auction House: Sotheby’s Dubai (2008)

- Sale Price: $217,000 (Estimate: $100,000–150,000)

- Details: This photograph, part of Neshat’s iconic Women of Allah series, features Farsi calligraphy superimposed on a veiled woman’s face. The sale exceeded expectations, reflecting strong demand for her politically charged imagery. (Fig. 1)[3]

Fig. 2: Shirin Neshat, Rebellious Silence, 1994, Ink on photograph,12 × 9 in (30.5 × 22.9 cm).

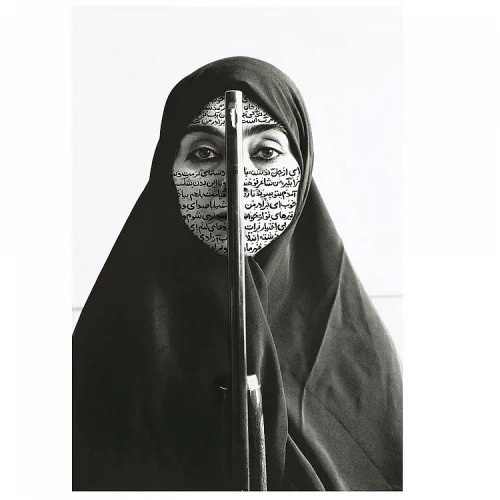

2. Rebellious Silence, (1994)

- Auction House: Christie’s Dubai (2008)

- Sale Price: $193,000 (Estimate: $80,000–120,000)

- Details: Another seminal work from Women of Allah, this piece juxtaposes Persian poetry with imagery of armed women, reinforcing Neshat’s critique of gender roles in Islamic societies. (Fig. 2)[4]

Fig. 3: Shirin Neshat, Untitled (from Soliloquy Series), 1999, Black-and-white photograph, ink, 40 × 30 in (101.6 × 76.2 cm).

3. Soliloquy, (1999)

- Auction House: Phillips London (2014)

- Sale Price: $365,000 (Estimate: $200,000–300,000)

- Details: A large-scale photograph from her Soliloquy series, this work explores themes of exile and cultural displacement, resonating with diasporic audiences. (Fig. 3)[5]

4. Passage (2001)

- Auction House: Sotheby’s New York (2021)

- Sale Price: $441,000 (Estimate: $300,000–500,000)

- Details: This haunting image from the Passage series reflects on mourning and ritual, further cementing Neshat’s reputation in contemporary photography. (Fig. 4)[6]

Fig. 4: Shirin Neshat, Untitled (from Passage), 2001, Cibachrome print, 38 7/10 × 60 in (98.4 × 152.4 cm).

5. Turbulent (1998) – Private Market Valuation

While Turbulent-Neshat’s Golden Lion-winning video installation-has never been publicly auctioned, its market value is estimated to exceed $700,000 in private transactions. (ArtTactic, 2023, p.34) However, due to the opaque nature of video art sales, this figure remains speculative. (Fig. 5)[7]

Fig. 5: Shirin Neshat, Turbulent, 1998, Black-and-white video installation (duration: 10 min).

Factors Driving Neshat’s Market Success

1. Institutional Recognition

Neshat’s retrospectives at the Tate Modern, Guggenheim Museum, and Hirshhorn Museum have amplified her market visibility. Institutional acquisitions often precede spikes in private collector demand (Daftari, 2013, pp.172-175)[8]

2. Political and Feminist Themes

Her works engage with postcolonial and feminist discourses, attracting collectors interested in Middle Eastern contemporary art. (Dabashi, 2010, pp. 312-315)[9]

3. Limited Editions

Most of Neshat’s photographs are released in small editions (often under 10), enhancing their scarcity and auction premiums. (Gladstone Gallery, 2023, p. 8)[10]

Challenges in Verifying Private Sales

Unlike paintings, video installations like Turbulent are typically sold through galleries (e.g., Gladstone Gallery) or acquired by museums without public price disclosures. While auction records for her photographs are well-documented, private sales rely on secondary sources, making precise valuations difficult.[11]

Shirin Neshat’s auction records demonstrate her strong market presence, particularly in photography. While her video works remain elusive in public sales data, their cultural significance ensures high demand among private collectors. Future research should track gallery transactions and institutional acquisitions for a fuller understanding of her market trajectory.

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. ArtChart (2023) The Market of Iranian Female Artists: Auction Analysis. (Accessed: 15 June 2024).

2. Middle East Quarterly (2015) 'Iranian Women Artists in the Global Market', Michigan Quarterly Review, 38(2), pp. 207-215. (Accessed: 15 June 2024).

3.Sotheby’s (2008), Modern and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art Sale [Auction catalogue]. 29 October 2008, Dubai.

4. Christie's (2008) Modern and Contemporary Arab, Iranian and Turkish Art. [Auction catalogue] 30 April 2008, Dubai, Lot 24. (Accessed: 15 June 2024).

5. Phillips (2014) Contemporary Art Evening Sale. [Auction catalogue] 14 October 2014, London, Lot 18.Available at: source (Accessed: 15 April 2025).

6.Sotheby's (2021) Modern and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art. [Auction catalogue] 28 April 2021, New York, Lot 112. (Accessed: 15 June 2024).

7.ArtTactic (2023) Middle Eastern Contemporary Art Market Report: Annual Review 2022-2023. London: ArtTactic Ltd., p. 34. ISBN: 978-1-916072-34-2.

8. Daftari, Fereshteh. (2013) Persia Reframed: Iranian Visual Arts in the 20th Century. London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 172-175. ISBN: 978-1-78076-506-3.

9. Dabashi, Hamid. (2010) Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers, pp. 312-315. ISBN: 978-0-934211-75-7.

10.Gladstone Gallery (2023) Shirin Neshat: Catalogue Raisonné of Editions (1993-2023). New York: Gladstone Gallery, p. 8. [Internal gallery publication].

11.Horowitz, Noah. (2022) Art of the Deal: Contemporary Art in a Global Financial Market. Revised edition. New York: Phaidon Press, pp. 112-115. ISBN: 978-0-7148-8025-6.

Image Sources:

Fig.1 Source: Shirin Neshat, Women of Allah #30 – Artsy

Fig.2 Source: Shirin Neshat, Rebellious Silence – Smarthistory

Fig.3 Source: Shirin Neshat, Soliloquy Series (Water Over Head) – Sotheby's Photographs Auction (2024)

Fig.4 Source: Note: Shirin Neshat – Artworks – Darz.Art Magazine

Fig.5 Source: Shirin Neshat, Turbulent – Artsy

Cover Image Source:

Cover photo: National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) (n.d.) [Cover image: Shirin Neshat] [Online image]. Photo courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York