Picasso’s Guernica-Art as a Mirror of War, Suffering, and Resistance

Figure 1: Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937). Oil on canvas, 3.5 x 7.8 meters. Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Art as a Mirror of Society

Art has always been more than a reflection of beauty; it is a mirror of society, a battleground for ideas, and a powerful force capable of shaping history. From the Renaissance to the modern era, artists have used their work not only to capture the world around them but also to challenge, provoke, and, at times, transform it. Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)’s Guernica stands as one of the most iconic examples of art as political protest, but he was far from alone in this endeavor. Across centuries and continents, artists like Diego Rivera, with his socialist murals, and Shepard Fairey, with his Hope poster for Barack Obama, have harnessed the visual language of art to communicate powerful political messages and rally support for their causes. Yet, the relationship between art and politics is not one-sided. While art has often been a tool for resistance and social justice, it has also been co-opted by those in power as a means of propaganda and control. Even Francisco Franco attempted to repurpose Guernica to promote his nationalist agenda, highlighting the dual nature of art as both a force for liberation and a potential instrument of oppression. By examining the ways in which art has been used to influence politics and vice versa we can gain a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between creativity, power, and the human experience.[1]

The Bombing of Guernica: A Catalyst for Artistic Response

At approximately 16:30 on Monday, 26 April 1937, the quiet town of Guernica was subjected to a devastating aerial assault that would forever mark it as a symbol of the horrors of modern warfare. For nearly two hours, warplanes of the German Condor Legion, under the command of Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, rained destruction upon the town. This attack was not merely an act of war but also a calculated experiment; Germany, led by Hitler at the time, had allied with the Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War and seized the opportunity to test new weapons and tactics. The brutal bombing of Guernica foreshadowed the ruthless strategies that would later define the Blitzkrieg, where intense aerial bombardment became a key precursor to ground invasions. Beyond its historical significance, Guernica has transcended its origins to become an enduring icon of modern art, often compared to the Mona Lisa in its cultural impact. Just as Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece epitomized the Renaissance ideals of serenity and self-control, Picasso’s Guernica stands as a profound commentary on the role of art in confronting the darkest aspects of human existence. Through its harrowing imagery, the painting asserts art’s capacity to challenge political crimes, resist the devastation of war, and confront the inevitability of death. In doing so, Guernica becomes more than a painting, it is a testament to art’s power to liberate the human spirit and affirm the individual’s resilience against overwhelming forces of oppression and destruction.[2]

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica: A Timeless Anti-War Masterpiece

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), (fig. 1) stands as one of the most powerful political statements in modern art, a monumental anti-war masterpiece that captures the devastation and suffering inflicted on innocent civilians during the Spanish Civil War. Created in response to the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Guernica, the painting is a harrowing depiction of the horrors of war, rendered in a stark monochromatic palette of black, white, and grey, oil on canvas. Measuring 3.5 meters tall and 7.8 meters wide, Guernica employs Picasso’s signature Cubist techniques fragmented forms, multiple perspectives, and dramatic chiaroscuro to evoke chaos, disorientation, and emotional intensity. By combining Cubist abstraction with sharp, angular forms, Picasso infused the work with an expressionist tone, amplifying its visceral impact.[3]

Symbolism in Guernica: A Multilayered Narrative

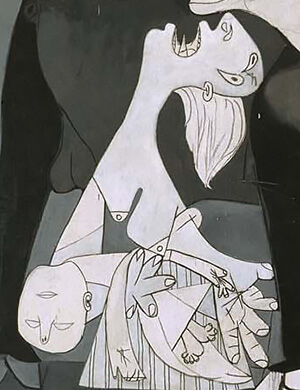

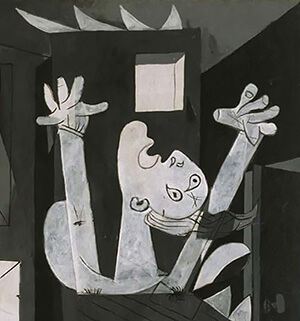

The painting is rich in symbolism, with key motifs deeply rooted in Spanish culture. Seven human figures and animals are arranged from right to left on a dark background. The bull, often interpreted as a symbol of brutality, resilience,[4] and fascism, and the horse, representing the suffering of Guernica’s people, dominate the composition.[5] The dove, barely visible and seemingly erased, symbolizes the loss of peace during the war, serving as a poignant reminder of the devastation that replaced harmony.[6] A grieving woman, her head tilted back and eyes rolled upward, cradles her dead child while reaching helplessly toward the sky. (See fig. 2) This tragic figure, reminiscent of Picasso’s portraits of Dora Maar whom he called The Weeping Woman, evokes the universal pain of maternal loss. To the right, another woman is depicted with her arms raised and mouth frozen in a scream, surrounded by flames. The triangular shapes around her symbolize the explosions caused by the bombing, emphasizing the chaos and destruction.[7](fig. 3)

Figure 2: Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937), close-up of the mother weeping over her dead child.

Figure 3: Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937), close-up of burning figure.

A light bulb at the top of the canvas symbolizes the destructive power of modern technology, adding a layer of irony to the scene.[8] (fig. 4) The only male figure in the painting lies dismembered on the ground, clutching a broken sword. (See fig. 5) His posture conveys a heroic but futile resistance against the overwhelming terror. Beside his hand, a ghostly flower emerges, symbolizing hope amidst the carnage. This fragile sign of resilience is echoed by the faint light emanating from a woman’s kerosene lamp elsewhere in the painting.[9] These elements, combined with hidden imagery such as a skull and daggers, create a multi-layered narrative that transcends its historical context. Guernica stands as a universal symbol of the horrors of war and a powerful call for peace.[10]

Figure 4: Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937), close-up of the light bulb and horse.

Figure 5: Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937), close-up of the man with a broken sword.

Picasso’s Anti-Fascist Activism and the Legacy of Guernica

Picasso’s engagement with anti-fascist activism during the 1930s and 1940s deeply influenced his work. Joining the French Communist Party in 1944, he viewed his activism as a natural extension of his life and art, using his celebrity status to expose the brutality of fascist regimes.[11] Guernica was commissioned by the Spanish Republican government for the 1937 Paris Exhibition, where it initially received little attention but later gained global acclaim as it toured internationally. The painting’s stark imagery and emotional depth drew attention to the atrocities of the Spanish Civil War, solidifying its status as a universal anti-war icon.[12]

Cubism’s Impact on Guernica: A Deeper Analysis

In the landscape of modern art, Cubism emerged as a groundbreaking movement, fundamentally reshaping traditional approaches to visual representation. Born from a desire to deconstruct reality and reconstruct it through the artist’s analytical lens, Cubism introduced a radical shift in how art could convey meaning. This transformation is vividly exemplified in Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, a politically charged masterpiece that harnesses Cubist techniques to articulate the chaos and devastation of war.[13] At its core, Cubism rejects the illusion of three-dimensional space, instead emphasizing a flattened, two-dimensional plane where objects are fractured into geometric forms and reassembled to present multiple perspectives simultaneously. This approach not only challenges the viewer’s perception but also invites a deeper, more interactive engagement with the artwork. In Guernica, Picasso masterfully employs these Cubist principles to depict the horrors of the 1937 bombing of the Basque town. The painting’s fragmented forms dismembered limbs, anguished faces, and splintered bodies create a sense of disarray and destruction that mirrors the brutality of the event.[14]

The Fragmented Body: Linda Nochlin’s Perspective on Modernity and Suffering in Guernica

Linda Nochlin’s theory of The Body in Pieces holds particular relevance for Picasso’s Guernica. In her exploration of fragmentation in modern art, Nochlin describes how the fragmented body became a central metaphor for the disintegration of the modern world. She argues that, the fragmented body in modern art is not merely a formal device but a profound metaphor for the disintegration of the modern world. It reflects the loss of wholeness, the breakdown of traditional values, and the alienation of the individual in an increasingly mechanized and dehumanized society.[15] This idea is vividly embodied in Guernica, where the fractured forms of human and animal bodies serve as powerful symbols of the chaos and devastation wrought by war.[16]

Nochlin writes, ‘’Art historians like myself, wrapped up in the nineteenth century and in gender theory, have a tendency to forget that the human body is not just the object of desire, but the site of suffering, pain, and death, a lesson that scholars of older art, with its insistent iconography of martyrs and victims, of the damned suffering in hell and the blessed suffering on earth, can never ignore.’’(Nochlin, 1994, p. 18)[17] This observation is crucial to understanding Guernica, where Picasso transforms the human body into a harrowing tableau of suffering. The fallen soldier with his severed arm, the anguished mother cradling her dead child, and the fragmented horse are not merely depictions of physical violence but also profound symbols of human vulnerability and mortality.[18]

Cubism and Emotional Depth: The Technical and Symbolic Mastery of Guernica

The Cubist technique of breaking forms into geometric shards amplifies this sense of disintegration, transforming the human body into a site of collective trauma and existential despair. Picasso’s use of iconic motifs, such as the bull and the horse, further demonstrates the influence of Cubist logic. These figures are deconstructed into geometric facets, yet they retain their symbolic resonance. The bull, often associated with Spain, and the horse, a representation of war’s devastation, are not rendered realistically but are instead reimagined as conceptual entities. This approach allows the viewer to engage with the painting on multiple levels, moving beyond literal interpretation to explore its allegorical depth. The dramatic interplay of light and shadow in Guernica also reflects Cubism’s fascination with contrast and form. The stark chiaroscuro heightens the emotional intensity of the scene, drawing attention to key elements of suffering and chaos. The absence of color, a striking departure from Cubism’s occasional forays into vibrant abstraction, further underscores the painting’s somber tone. By stripping away color, Picasso amplifies the bleakness of the subject matter, aligning the aesthetic with the desolation it portrays.[19]

The Enduring Legacy of Guernica

Beyond its artistic significance, Guernica carries a powerful political legacy. Picasso insisted that the painting remain abroad until Spain restored democracy, and it was finally returned to Spain in 1981, after Picasso’s death.[20] Today, it resides in the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, where it continues to inspire anti-war movements and serve as a poignant reminder of art’s power to provoke thought and incite change.[21]

Picasso’s Guernica is not only a technical masterpiece but also a profound historical document.[22] Its innovative visual language and enduring legacy have influenced generations of artists, underscoring the role of art as a tool for resistance and a means of communicating universal truths.[23] Through its stark imagery and emotional depth, Guernica remains a powerful indictment of violence and a timeless plea for peace, embodying the enduring power of art to inspire social change.[24]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. MyArtBroker (n.d.) Picasso’s political art. (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

2. PabloPicasso.org (n.d.) Guernica, 1937 by Pablo Picasso. (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

3. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

4. Ibid.

5. PabloPicasso.org (n.d.) Guernica, 1937 by Pablo Picasso. (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

6. Artsper (n.d.) Artwork analysis: Guernica by Picasso. (22 March 2025).

7. Ibid.

8. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

9. Artsper (n.d.) Artwork analysis: Guernica by Picasso. (22 March 2025).

10. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

11. MyArtBroker (n.d.) Picasso’s political art. (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

12. PabloPicasso.org (n.d.) Guernica, 1937 by Pablo Picasso. (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

13. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

14. Ibid.

15. Nochlin, Linda. (1994) The body in pieces: The fragment as a metaphor of modernity. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 7–29.

16. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

17. Nochlin, Linda. (1994) The body in pieces: The fragment as a metaphor of modernity. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 7–29.

18. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

19. Ibid.

20. PabloPicasso.org (n.d.) Guernica, 1937 by Pablo Picasso. (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

21. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

22. MyArtBroker (n.d.) Picasso’s political art. (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

23. PabloPicasso.org (n.d.) Guernica, 1937 by Pablo Picasso. (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

24. Creative Flair (n.d.) Picasso’s Guernica: A technique exploration. (20 March 2025).

Image Credits:

All images of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) are sourced from EmptyEasel, (Accessed: 15 October 2023).