Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party

Judy Chicago: A Feminist Pioneer Rewriting Art History

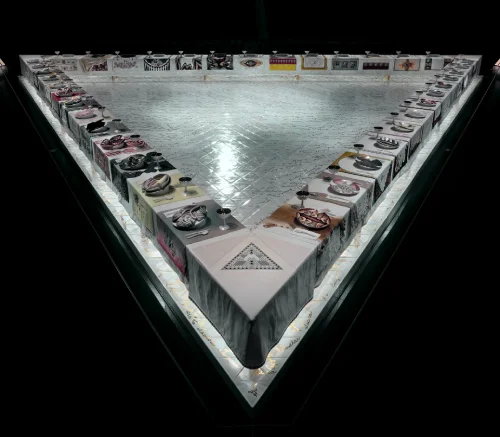

Judy Chicago, a pioneering figure in the feminist art movement of the 1970s, reshaped the boundaries of art while challenging traditional narratives of gender, identity, and historical representation. With works that critically examined the exclusion of women from art and history, Chicago sought to reposition women not as passive subjects but as active agents whose contributions deserved recognition on equal terms with men. Her groundbreaking installation, The Dinner Party (1974-1979),(Fig. 1) is perhaps the most iconic example of her efforts to not only celebrate women’s achievements but also to deconstruct the gendered history of art itself.[1]

Fig. 1. Judy Chicago, the Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Installation.

A Monument to Women’s Erased Legacy

The Dinner Party is a monumental, multi-media installation that reflects the significant contributions of women throughout history, providing a bold platform for rethinking and retelling women’s stories across various cultures and time periods. Through this work, Chicago confronts the systemic erasure of women from historical narratives, offering a radical reinterpretation of the roles that women have played in shaping history, art, and culture. The piece is a direct response to the exclusion of women from the male-dominated art world and offers a bold assertion of female power and agency.[2]

The Triangular Table: A Symbol of Equality and Historical Progression

The installation consists of a large, triangular table, which symbolizes equality and harmony, each side measuring 48 feet long. Each of the three wings of the table represents a distinct historical period. [3] The first spans from prehistory to the emergence of patriarchy; the second covers the rise of Christianity through the Reformation; and the third wing focuses on the 17th through the 20th centuries. This division highlights the progression of women’s roles from a time of relative social and political power to their eventual subjugation in patriarchal societies.[4]

Place Settings: Honoring the Forgotten and the Celebrated

The table features 39 individual place settings, each dedicated to a historically significant woman from across the ages. These women, both celebrated and forgotten, include figures from mythology, politics, art, and literature. The place settings themselves are carefully designed to symbolize the individual woman’s achievements, often incorporating ceramic plates decorated with motifs of female genitalia or flowers, a deliberate reference to female sexual power. This imagery, prominently displayed on each plate, serves as a challenge to the patriarchal traditions that have historically silenced or marginalized women’s voices.[5]

Reclaiming ‘Women’s Work’ as High Art

Each place setting also includes a ceramic object designed to evoke the form of a vagina or flower, accompanied by a gilded cup, knife, fork, and an embroidered tablecloth. The inclusion of these objects underscores Chicago’s commitment to reclaiming traditional ‘’feminine’’ crafts, such as embroidery and ceramics, which had historically been relegated to the domestic sphere and dismissed as inferior forms of art. By elevating these crafts to the status of high art, Chicago challenged the traditional divisions between “fine art” and “women’s work,” bringing them into the center of artistic discourse.[6]

Sacred Geometry: The Triangle as a Feminist Symbol

The work’s design also contains a deeper symbolic significance. The triangular table, for instance, alludes to the ancient symbol of female sexuality and power, reinforcing the idea that women, through history, have had the potential for political and social influence. The 13 place settings on each side of the table range from goddesses of ancient civilizations to modern figures and artists such as Frida Kahlo, Artemisia Gentileschi, and, ultimately, Georgia O'Keeffe, who was the only living woman present during the installation. It also echoes the Christian imagery of the Last Supper, drawing a powerful parallel between the act of women reclaiming their place at the table of history and the cultural significance of this biblical scene.[7]

Vaginal Imagery: A Provocative Challenge to Patriarchal Art

One of the most provocative elements of The Dinner Party is the portrayal of female genitalia in the ceramic designs. These bold, dynamic images are presented in contrast to the phallic imagery that dominates much of art history, creating a deliberate subversion of the conventional representations of gender. Chicago’s incorporation of these images was not only a reclamation of female sexual power but also a challenge to the historical silencing of women’s bodies in art. In doing so, she sought to create a space where women could assert their presence and significance without fear of shame or repression.[8]

Critical Backlash: Why The Dinner Party Shocked the Art World

While critics, such as Hilton Kramer from the New York Times, dismissed the work as an “offensive slander against the feminine imagination”, this backlash highlights the degree to which Chicago’s work challenged the status quo. By placing female genitalia at the center of the work, Chicago confronted the very core of gendered artistic traditions and began a broader cultural conversation about the representation of women in art.[9] As Lucy Lippard observes, Chicago intentionally moved away from avant-garde conventions and symbolic imagery, rejecting the idea of interpretive abstraction in favor of a direct engagement with the subject of womanhood.[10]

Collective Masterpiece: The Feminist Collaboration Behind the Work

Beyond its thematic and aesthetic power, The Dinner Party is also remarkable for its collaborative nature. Chicago worked with a diverse team of over 400 collaborators, including both women and men, to bring the work to life. This collective effort stands in stark contrast to the heroic individualism often associated with avant-garde art and reflects the feminist ethos of shared experience and collective empowerment. The contributions of each individual were documented, ensuring that the collaborative process was recognized and celebrated.[11]

Legacy: How The Dinner Party Redefined Feminist Art

Through The Dinner Party, Judy Chicago has created an enduring symbol of feminist art—one that challenges the patriarchal structures of the art world, redefines the boundaries of artistic practice, and offers a new, inclusive narrative for future generations. By bringing women and women's handicrafts into the spotlight and giving them a place at the table, Chicago redefines their agency and provides a powerful vision of what it means to create art that is both personal and political.[12]

Essay by malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. Chicago, Judy, Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist. Dinner Party, 1975.

2. Lucie-Smith, Edward, Judy Chicago: An American Vision (Watson-Guptill, 2000). p.59.

3. Barnet, Sylvan, A Short Guide to Writing about Art (Pearson: 2011) p.231.

4. Lucie-Smith, Edward, Judy Chicago: An American Vision (Watson-Guptill, 2000). p.62.

5. Mohtasham, Sam and Salemian, Elham 2021, “Judy Chicago: Creation and Activism”. Kaarnamaa; A Journal of Art History and Criticism, V 5, N.3. Fall 2021.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Jones, Amelia, Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in the Feminist Art History (University of California Press: 1996), P.26.

9. Kramer, Hilton, 1980, “Judy Chicago's 'Dinner Party' Comes to Brooklyn Museum; Art: Judy Chicago 'Dinner Party'”. NYT. (Mohtasham, Sam and Salemian, Elham 2021, “Judy Chicago: Creation and Activism”. Kaarnamaa; a Journal of Art History and Criticism, V 5, N 3, Fall 2021).

10. Lippard, Lucy, 1980, "Judy Chicago's Dinner Party". Art in America, P 118. (Mohtasham, Sam and Salemian, Elham, 2021, “Judy Chicago: Creation and Activism”. Kaarnamaa; A Journal of Art History and Criticism, V 5, N 3, Fall 2021).

11. Ibid.

12. Chicago, Judy, the Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation. San Francisco: Prestel, 2007.

Image and Cover Image Source:

Chicago, Judy. (1979) The Dinner Party [Mixed media installation]. Brooklyn Museum, New York. (Accessed: 20 February 2025).