The State of Being in Hamoun Alipour's Self-Portraits

Self-Portraits as Meta-Self-Portraits

In an artist's artistic journey, a self-portrait is considered a type of "personal revelation" through which the artist depicts not only external forms and shapes but also their inner and psychological states within the technique and brushstrokes. The expression of the painter's psychological and emotional states can be examined through the choice of color, the type of figure, and the features of the face. It is where the human puts the "self" at the center and seeks "representation," "creation," and perhaps "re-creation of the self" in line with this revelation, and it is precisely here that one can acknowledge that in some cases, the "self" becomes the "meta-self." A meta-self that emerges from ideas, society, and culture and is returned to society through self-portraits. The historical process of portraiture can be found in the late Renaissance and the Baroque era, where everyone was inherently a king, and each portrait represented the obvious individuality of the subjects[1], and the unique mastery of each artist confirmed this kingdom and self-centeredness. Throughout history, the self and meta-self have flourished with the advent of technology and the modern era, as well as the growth of the humanities and the analysis of artistic achievements by them. Today, self-portraits examine not only the inner and psychological dimensions of an artist but also their history and geography, and can be made available to future generations as a historical document.

Expressing Shared Pain

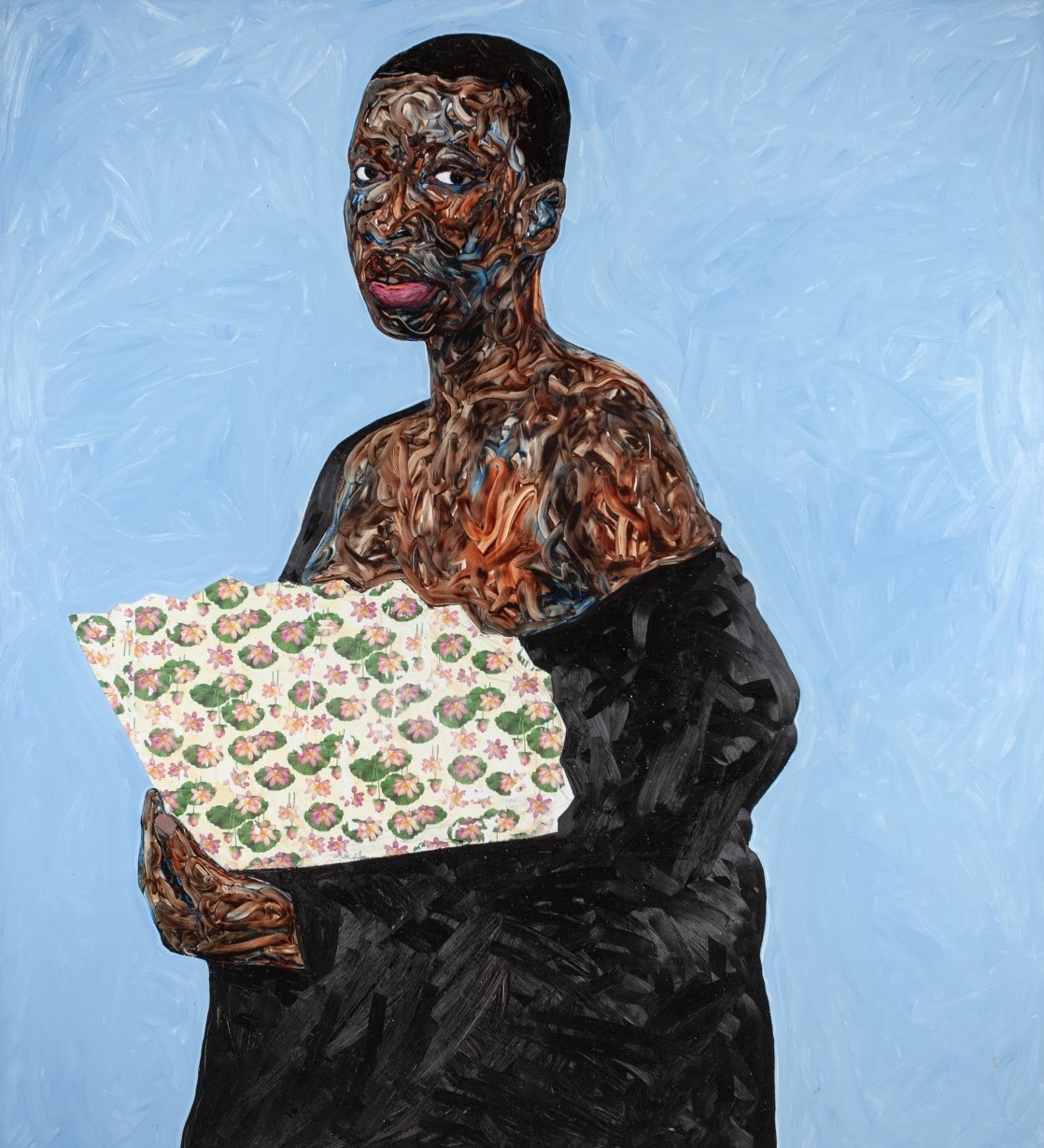

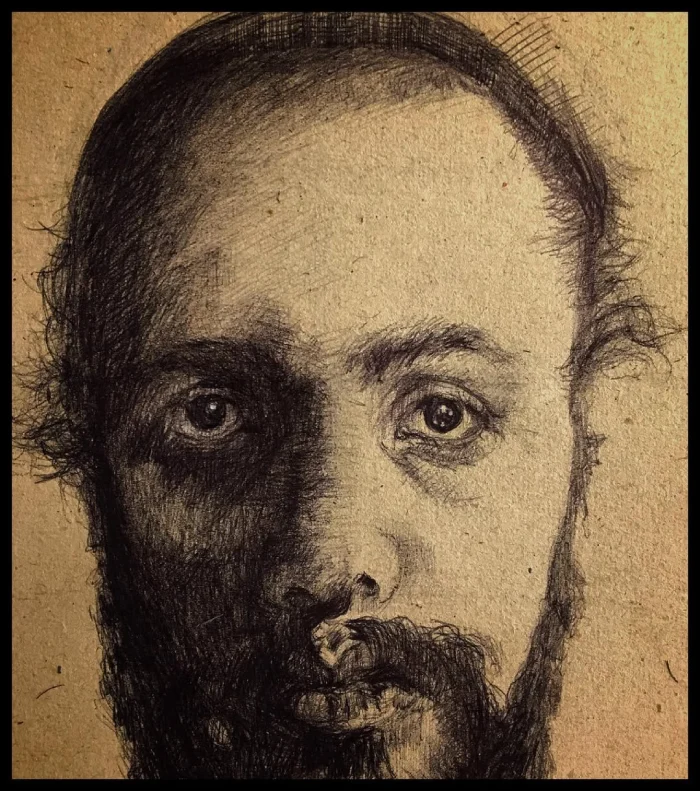

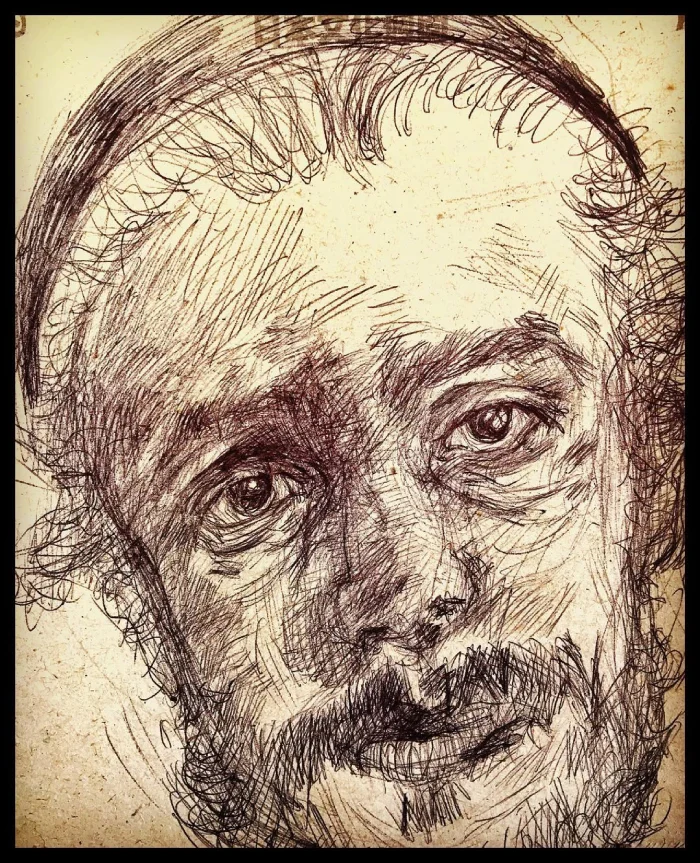

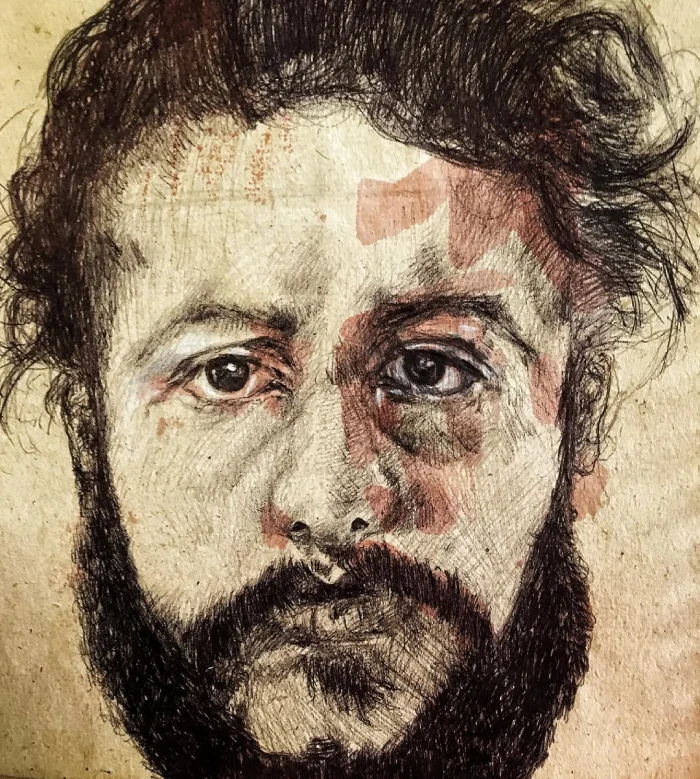

Hamoon Alipour's self-portraits (born 1991), which have been recorded as exercises and in small dimensions in the artist's sketchbook, have the potential for analysis and examination in form and content. Hamoon uses the medium of painting, and sometimes photography and video, to create these self-portraits. In his photos, the artist captures various states of the head and face and their movements in the moment by placing images next to each other in a frame. These photos contain various states such as pain, suffering, screaming, anger, and mourning, and sometimes include the most private emotional dimensions of every human being. By "revealing the deepest human pains" and sharing various aspects of the most private expressions of his face, the artist awakens "shared pains" within us and screams them out (Image 1). In examining the artist's paintings of his face, we come across personal expressions in the space of the works that are visible. The most expression in these paintings is related to the eyes. The eyes are sunken, sad, and pain-stricken, staring fixedly somewhere; the corners of the eyes are drooping and introverted, making them appear rounder and more circular. In most images, the light source is located on the left side, and the left eye has more light reflection than the right eye (Image 2), and this, along with the bulge under the eyes, increases the intensity of pain and emotional expression in the portrait. In the examination of one of Rembrandt's self-portraits, it is stated that the appearance of wrinkles and bulges under the eyes all indicate that the owner of the painting is exhausted. Upon further examination of the painting, we realize that although his left eye shows a state of pain and suffering, it is still penetrating, and in the right eye, although it looks painful, traces of being taken aback by what he sees can be read, and when we pay attention to both eyes together, we find that these eyes have a calm, indifferent, cold, and openly examining state.[2] And in the midst of these examinations, we come to the conclusion that in different eras and different historical periods, these interpretations of artists' self-portraits can be generalized and repeated, and perhaps this is a sign of the nature and essence of art within artists.

The Role of Technique in Expressive States

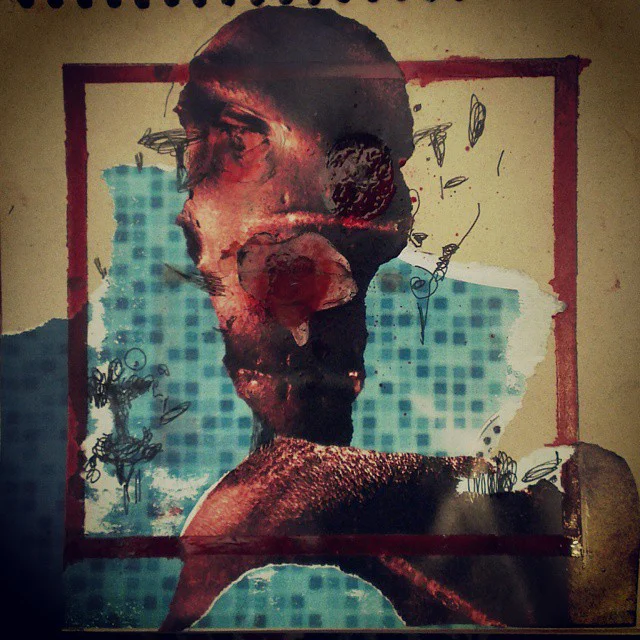

In some cases, the lines of the paintings, while maintaining their "strength and structure," move toward "decay and annihilation" and depict visual disturbances within the strokes (Image 3). These "expressive statements" in the manner of execution, allow access to the artist's psychological states, which, while forming commonalities in the space of the works, also carry differences in details with them. In a series entitled "My Self-Portrait is Changing," the artist shares his concern about the changes in his face with the audience (Image 4). Part of Lucian Freud's experiences[3] in portraiture deals with these changes in the face and the difference in the execution of the work. He says in a part of his speech: "What I have never gotten used to is the 'change in people's conditions' from one day to the next. Although I have tried to control this change in temperament as much as possible by working constantly and absolutely at all times, my conditions are so different from day to day that I am surprised that my paintings come to fruition." The paradox of portraiture is that the subject is constantly moving; the living being is constantly in flux both physically and psychologically; conditions change; energy goes up and down.[4]

The Contrast of Redness and Coldness

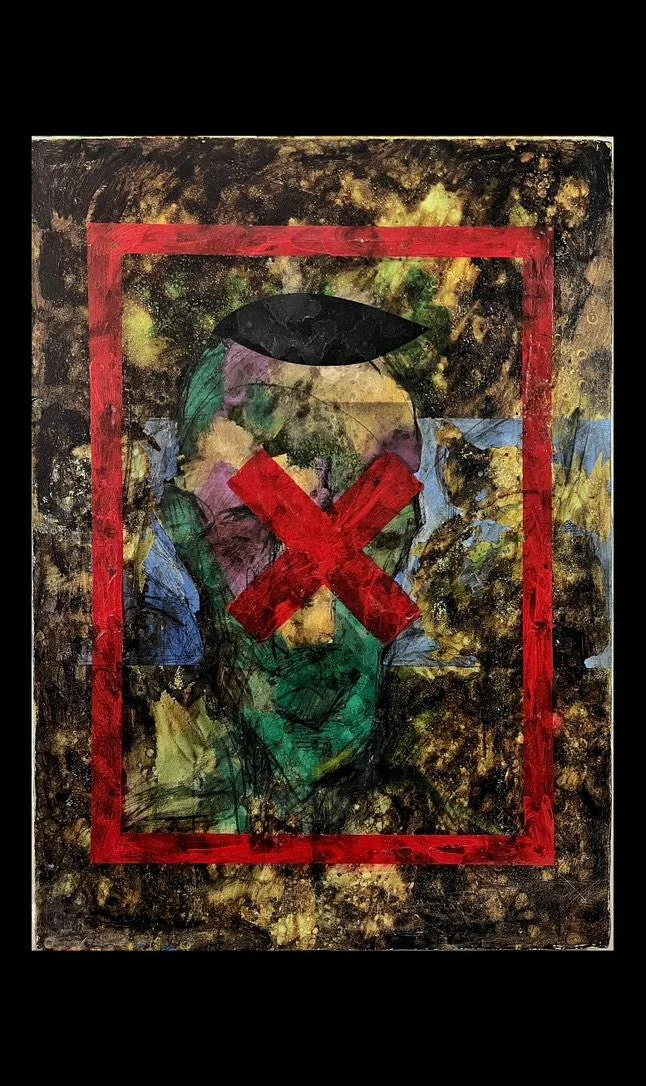

In a more detailed examination of these self-portraits, we come across the color red. Wherever the artist intends to use colors, alongside various grays, he has shown us the color red as his prominent choice, sometimes in the form of a hat he wears, and sometimes in the form of spots of color that are scattered on his face (Image 5). And in other images, this red color is spread across the face and covers the expanse of the artist's face in the photos (Image 6). It is as if the artist, by choosing the warmest possible color, which is in contrast to his calm face and soulless gaze, places a deep contradiction before the audience, and the phrase "sad oriental" and perhaps "angry oriental" can be felt behind these images.

The Pure Form of Art or its Efficiency?

To analyze the meaning in these artistic self-portraits further, we can create new and efficient meanings and, "according to Cassirer[5], put art from the 'pure form of truth' at the service of another goal." (Babak Ahmadi, 2011, p. 284) But self-portraits, under the guise of interpretations and concepts and under the shadow of "modern hermeneutics," are on the one hand a full representative of the art of the time and on the other hand an expression of the era in which they are located. Wittgenstein[6] speaks of "the state of affairs" in his logical-philosophical treatise and says that what cannot be expressed can show itself. (Ibid., p. 275) Wittgenstein's discussions have been used to "discover the functions of language" and the reasons for using words in sentences. He did not see the issue as meaning and artistic creation, but rather emphasized their function to achieve their logical essence (Ibid., p. 278). If we consider the image as a type of language, we can, alongside the nature of artistic creation, take a look at the "function of self-portraits" in "expressing historical eras," and accordingly, everyone can create a kind of personal game to express their own experience or "their inner experience." In this regard, Wittgenstein says: A voice that no one understands but seems to be understood by me can be called "personal language."[7] (Ibid., p. 279)

1. Hamoon Alipour, Self-Portrait, Photo, 120×120, 2017.

2. Hamoon Alipour, Self-Portrait, Pencil on Paper, 20×20, 2020.

3. Hamoon Alipour, Self-Portrait, Pen on Paper, 20×20, 2020.

4. Hamoon Alipour, From the series "My Self-Portrait is Changing," Oil on Canvas, 50 x 70, 2011.

5. Hamoon Alipour, Self-Portrait, Pencil on Paper, 20×20, 2020.

6. Hamoon Alipour, Self-Portrait, Collage on Cardboard, 20×20, 2015.

Sources:

1. Spur, Dennis. 2013. The Incentive of Creativity in the Historical Course of Arts. Translated by Alam, Amir. Jalaluddin., Second Edition. Tehran: Niloofar and Friends Publications, pp. 291-292.

2. May, Charles L. 1995. The Face of Rembrandt. Translated by Bahrambeigi, Ali.Asghar., First Edition. Tehran: Scientific and Cultural Publishing Company, pp. 375-377.

.3 Lucian Michael Freud.(1922 Germany-2011 UK)

4. Gayford, Martin. 2020. Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud. Translated by Shahamipour, Shervin., Second Edition. Tehran: Nazar Research and Culture Institute of Publishing.

5. Ernst Cassirer.(1874 Germany-1945 US)

6. Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein.(1889 Austria-1951 UK)

7. Ahmadi, Babak. 2011. Truth and Beauty. Twenty-First Edition. Tehran: Nashr-e Markaz, pp. 277-284.

Source of Images:

Hamoon Alipour, Available at: [Images from Personal Instagram Page]. (Accessed on: May 9, 2025).

Firoozeh Sabouri.