The Transformative Art of Davood Emdadian

Shifting the Boundaries of Reality:

The Artistic Journey of Davood Emdadian

Davood Emdadian (1944–2004) was one of Iran's most prominent contemporary painters. Born in Tabriz, he began his artistic education at the Mirak School of Fine Arts, where he mastered the foundational principles of art and held his first exhibitions. Emdadian later studied at the Faculty of Decorative Arts and pursued a Master’s degree in Visual Arts at the Sorbonne University in Paris, France. [1]

In the early stages of his career, Emdadian’s affinity for nature became evident. Initially influenced by the Barbizon School and Russian landscape painters, he later adopted the color techniques of the Impressionists. By the early 1970s, he introduced a quasi-Cubist geometric abstraction into his Impressionist landscapes, a method he also applied to figurative works. By the mid-1980s, Emdadian had developed a distinct personal style, characterized by a poetic and visual interpretation of nature. [2]

Redefining Logic and Scale: Emdadian’s Artistic Vision

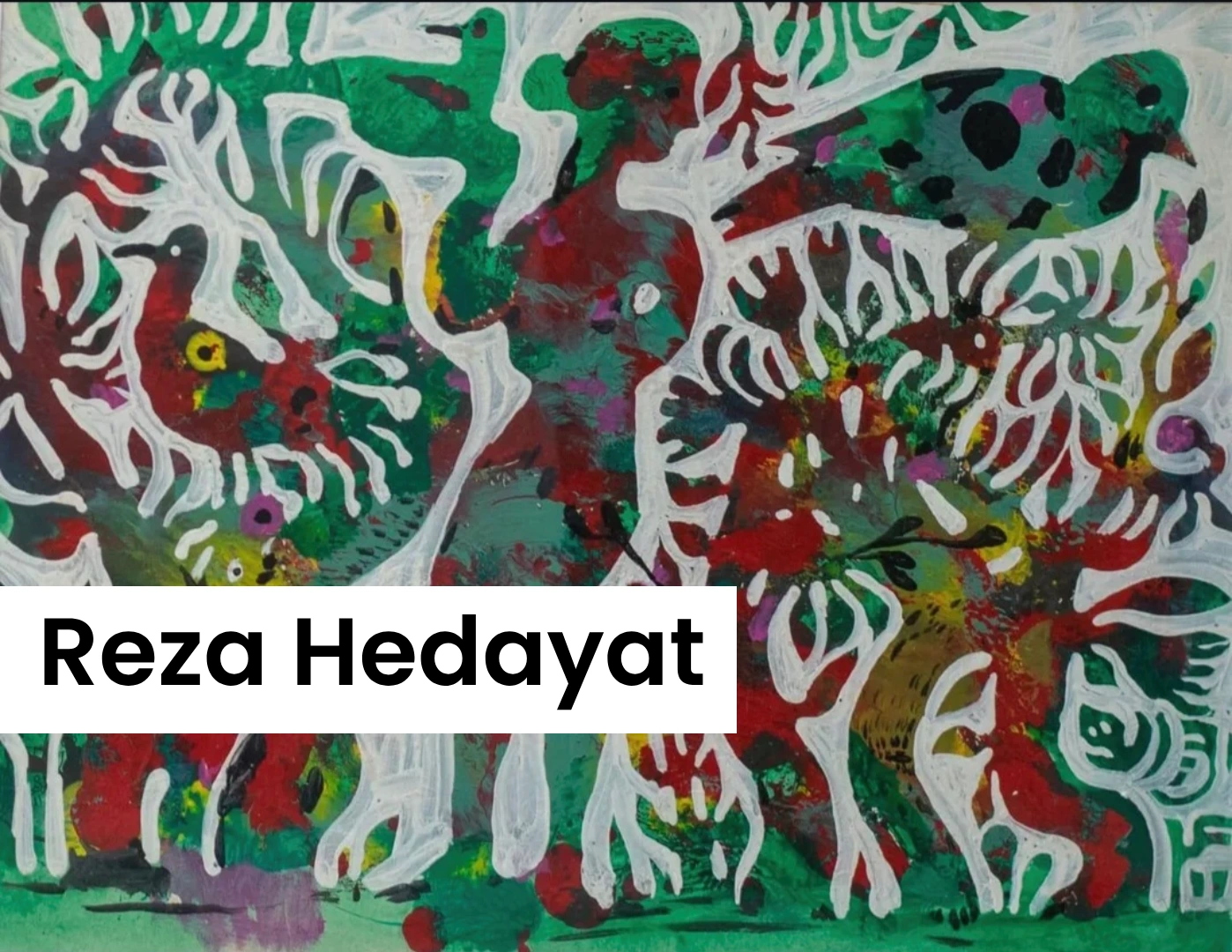

Emdadian’s paintings challenge the boundaries of logic and disrupt conventional scales. Over time, his focus on trees as a central subject led to the creation of unique forms that defy categorization, placing his work at the intersection of various styles and genres.

The Interplay of Imagination and Reality

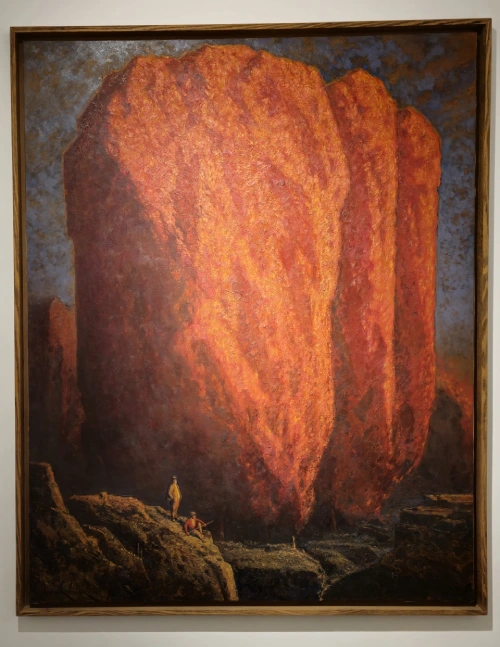

Light and shadow play pivotal roles in Emdadian’s works. Transparent and luminous colors, combined with bold and directional brushstrokes, showcase his unparalleled technical mastery. His paintings occupy a liminal space between reality and imagination, drawing inspiration from nature while reflecting his inner world. The trees in his works are often depicted on a monumental scale, disrupting the viewer’s visual expectations and suggesting something beyond the physical form of the tree itself. (Image 1) The diverse palette of colors, devoid of seasonal indicators, conveys sensations of warmth and cold, creating a dynamic visual experience. As one critic noted, “In Emdadian’s works, colors ignite and turn to ash. His reds are not of life but of wounds and blood. Through color, Emdadian cries out a burnt truth.” [3]

A 1985 Commentary on Emdadian’s Work

In a 1985 feature in the French newspaper 24 heures, Emdadian’s works were described as “relatively classical.” The artist explained, “I merge myself with everything I see. When a work delights and moves me, I incorporate its visual traditions into my own, provided it enriches my inspiration. I can be Eastern, Romantic, symbolic, or abstract, drawing from all sources.”

The article further elaborates: “These colossal trees, standing like sculptures among uneven blocks and pruned gardens, symbolize life, growth, resilience, and triumphant nature for Emdadian. Light bathes these giant groves, which sometimes shelter small, joyful humans, reminiscent of the protected gardens of Eden under intimate guardianship. From this luminous delicacy, borrowed from the Impressionists, a kind of magic emerges a timeless secret of all distinguished forests, where divine whispers reside among mesmerizing leaves.” [4]

The Sublime in the Enchanting Forms of Trees

The forms of trees in Emdadian’s paintings have evolved over time. At times resembling uniform, monochromatic clouds with broad surfaces, at others like massive rocks emerging from the earth, or even modernist abstractions, Emdadian skillfully navigates these definitions without settling into any single one. The juxtaposition of tiny human and animal figures against the vastness of the trees heightens the contrast, emphasizing the grandeur of the arboreal forms. (Image 2) These monumental masses evoke a sense of the sacred, transcending nature and reality to become something sublime. The viewer is confronted with a reality beyond nature, as if the trees have journeyed through the artist’s soul before manifesting on the canvas. In many works, the tree trunks are absent, and the forms maintain their integrity from top to bottom, unaltered and unified.

The Heroic Presence of Trees

When immersed in Emdadian’s paintings, the trees immediately captivate the viewer. “Through their grandeur, beauty, and presence, they forge a powerful connection between sky and earth. Their dazzling foliage, radiating light, draws the viewer’s gaze at first glance. In his works, the tree becomes a character, akin to the hero of an endless story.” [5]

Recognition and Legacy

Throughout his career, Emdadian exhibited his works extensively both in Iran and abroad, earning numerous accolades, including the 4th Prize at the *International Exhibition of European Art in Karlsruhe, Germany [6], the Taylor Foundation Award [7], and the Charles Ollmon Foundation Award. [8][9]

The Twentieth Anniversary of the Artist’s Passing

In 2025, 0098 Gallery dedicated one of its projects to Emdadian, marking the twentieth anniversary of his passing. The exhibition featured his drawings and select paintings, organized in collaboration with the Emdadian Foundation. Titled Drawings, the exhibition highlighted the artist’s dynamic and bold lines, meticulously capturing trees in diverse forms. (Image 3) The variety and technique of the drawings reveal Emdadian’s 25-year dedication to creating these extraordinary arboreal forms, showcasing the culmination of his artistic journey.

1. Davood, mdadian (2003). Untitled. 0098 Gallery, Tehran, Firoozeh Saboori picture.

2. Davood, mdadian (2003). Untitled. 0098 Gallery, Tehran, Firoozeh Saboori picture.

3. Davood, mdadian (2003). Untitled. 0098 Gallery, Tehran, Firoozeh Saboori picture.

References:

1. Darz (n.d.) Davoud Emdadian. (Accessed: 15 March 2025).

2. Herfeh – Honarmand (n.d.) Davoud Emdadian. (Accessed: 15 March 2025).

3. Poshtebam (n.d.) From Kandinsky to Emdadian. (Accessed: [insert date]).

4. Darz (n.d.) Archive: La Montagne – Note on Emdadian. Available at: https://darz.art/fa/magazine/archive-la-montagne-note-emdadian/854 (Accessed: 15 March 2025).

5. Avam Magazine (n.d.) Exhibition Report: Davoud Emdadian. (Accessed: [insert date]).

6. International European Art Show (1979) Karlsruhe Offerta, Germany.

7. The Taylor Foundation (n.d.) Founded in 1844 by Baron Isidore Taylor (1789–1879).

8. Charles Oulmont Foundation (2003) Charles Oulmont Foundation.

9. Darz (n.d.) Davoud Emdadian. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Firoozeh Saboori