Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen

A Feminist Critique of Domesticity and Its Enduring Relevance

Martha Rosler and the Politics of Domestic Space

Martha Rosler (b. 1943) stands as a pivotal figure in feminist art and critical theory, interrogating the intersections of gender, labor, and power through incisive critiques of domesticity, media, and institutional structures. Emerging during the 1970s amid second-wave feminism and the rise of Conceptual art, Rosler’s multidisciplinary practice spanning video, photography, performance, and writing challenges patriarchal frameworks that naturalize women’s roles in the private sphere while exposing systemic inequities in public institutions. Central to her oeuvre is the dismantling of binaries: between private and public, individual and structural, art and activism.[1]

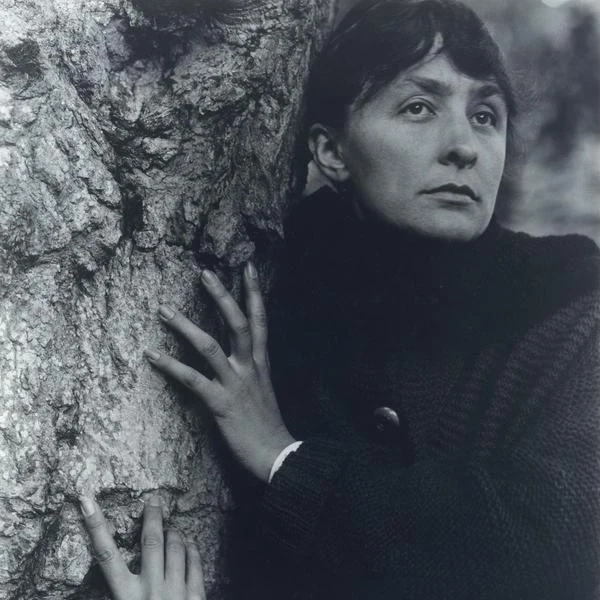

Fig. 1: Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975, Video art.

Deconstructing Domestic Semiotics: Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975)

Rosler’s landmark video Semiotics of the Kitchen epitomizes her subversive approach. Parodying televised cooking shows, she adopts the persona of a housewife to alphabetically catalog kitchen implements, pairing each with absurd, violent gestures that rupture their domestic utility. Clad in an apron and standing before a sparse kitchen set, Rosler transforms a knife into a weapon, thrusts a rolling pin with aggression, and clangs a chopper into a metal bowl, creating dissonance that disrupts the kitchen’s image as a site of nurturing calm. Her deadpan delivery and minimalist aesthetic reject the polished artifice of mass media, aligning with Conceptual art’s prioritization of ideas over form.[2]

Rooted in second-wave feminism’s “consciousness-raising” ethos, the work critiques Cold War-era ideologies that relegated women to domestic roles. Rosler employs semiotics the study of signs and meaning to reframe kitchen tools as linguistic symbols laden with patriarchal assumptions. A “Mother” placard visible in the set underscores the cultural coding of domestic labor as innate “women’s work,” while Rosler’s gestures expose these tools as literal and metaphorical instruments of oppression.[3] The video’s fusion of avant-garde performance and feminist theory urges viewers to interrogate politicized meanings embedded in everyday spaces[4], resonating with the mantra “the personal is political” (Hanisch, Carol. 1970).[5]

Intersection with Linda Nochlin’s Feminist Critique

Rosler’s critique aligns with Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? which argues that institutional barriers not innate talent historically excluded women from artistic recognition. Nochlin contends that women were relegated to roles as subjects rather than creators, a systemic erasure mirrored in Rosler’s portrayal of domestic rituals.[6] By transforming cooking demonstrations into absurd, violent routines, Rosler subverts the idealized housewife archetype, just as Nochlin challenges the myth of the solitary male genius. Both theorists emphasize systemic critique over individual agency. Nochlin dismantles the structures defining artistic “greatness,” while Rosler reveals how domestic labor is devalued and invisibilized. Their works converge in exposing socially constructed roles: Rosler’s aggressive performance disrupts passive femininity, while Nochlin’s analysis demands institutional accountability for gendered exclusion.[7]

Judith Butler and the Performativity of Gender

Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity further illuminates Rosler’s work. Butler posits that gender is not inherent but constituted through repeated acts shaped by societal norms.[8] In Semiotics of the Kitchen, Rosler embodies a 1950s-style cooking host, yet her exaggerated, mechanical gestures stabbing with a knife, flinging imaginary ladle contents subvert expectations of nurturing domesticity.[9] This dissonance aligns with Butler’s assertion that performative disruptions can destabilize rigid gender norms. Rosler’s use of alphabetical order, which devolves into chaos, mirrors Butler’s argument in Gender Trouble (1990) that subverting linguistic and symbolic structures can challenge hegemony.[10] By reimagining kitchen tools as weapons, Rosler rejects the association of women with passive objectification, transforming the kitchen into a site of resistance.[11]

Enduring Relevance and Contemporary Discourse

Rosler’s legacy endures in debates about care labor, intersectional feminism, and anti-capitalist critique. Her work presages contemporary discussions on the visibility of reproductive labor and the politics of representation, affirming her assertion that “there is no such thing as the apolitical.” (Molesworth, 2000) As unpaid domestic work and gendered inequities persist, Semiotics of the Kitchen remains a vital critique of how societal expectations shape performative roles.[12] Despite her groundbreaking contributions, Rosler’s work has been marginalized within narratives of Institutional Critique, which historically prioritized male artists. This omission reflects a broader dismissal of domestic themes as non-conceptual. Yet Rosler’s interrogation of media semiotics aligns her with Duchampian traditions of institutional subversion, expanding critique to address patriarchal and capitalist systems.[13]

Conclusion: The Kitchen as a Site of Resistance

Semiotics of the Kitchen transcends its historical moment, urging audiences to confront enduring structures of gender inequality. Rosler’s work reminds us that the kitchen, once a symbol of confinement, can also be a space of transformation. As feminist movements evolve, her legacy challenges us to reimagine art, activism, and daily life, proving that subversion begins in the everyday.

Essay by malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. Molesworth, Helen, 2000. 'House Work and Art Work', October, 92 (Spring), pp. 71-97. [Accessed 15 May 2016].

2. Ibid.

3. Goodman, Emily Elizabeth, 'Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen', Smarthistory. [Accessed 7 March 2025].

4. Molesworth, Helen, 2000. 'House Work and Art Work', October, 92 (Spring), pp. 71-97. [Accessed 15 May 2016].

5. Hanisch, Carol. 1970. "The Personal is Political." In Notes from the Second Year:

Women's Liberation, pp. 76-78.

6. Nochlin, Linda. 'Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?' in Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, ed. by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: Harper & Row, 1982), pp. 145-176.

7. Sammlung Verbund (2016) Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s: Works from the Sammlung Verbund Collection, Vienna, 7 Oct 2016–15 Jan 2017, p. 40. The exhibition comprises over 200 major works by forty-eight international artists.

8. Butler, Judith, 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, pp. 1-25.

9. Goodman, Emily Elizabeth, 'Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen', Smarthistory. [Accessed 7 March 2025].

10. Butler, Judith, 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, pp. 1-25.

11. Molesworth, Helen, 2000. 'House Work and Art Work', October, 92 (Spring), pp. 71-97. [Accessed 15 May 2016].

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

Image and Cover Image Source:

1. Rosler, Martha. (1975) Semiotics of the Kitchen (Film Stills) [Photographic stills from video performance]. (Accessed 15 May 2016).