Revisiting the Nude-Alice Neel’s Subversion of the Male Gaze

Introduction: Alice Neel and the Humanist Revolt Against Abstraction

Among modernist artists who prioritized emotional and sociopolitical resonance over formal conventions, few subverted technical perfection as radically as Alice Neel (1900–1984). Her portraits raw, psychologically immediate, and unapologetically human rejected the cold abstraction dominating 20th-century art, instead weaponizing the figure to expose fissures of race, class, and gender. For Neel, painting was not an exercise in aesthetic detachment but a visceral act of bearing witness.[1] As she famously declared, “I am against abstract and non-objective art because such art shows a hatred of human beings. It is an attempt to eliminate people from art, and as such, it is bound to fail” (Carroll, 2021, para. 5).

Psychological Transference: Portraiture as Collaborative Witness

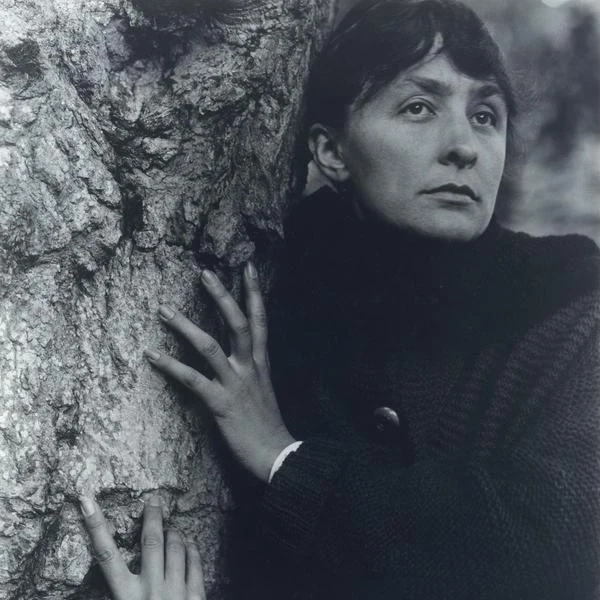

Fig. 1: Alice Neel, Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas

Neel’s portraits transcend mere representation, embodying a charged psychological exchange between artist and subject a process art historian Jeremy Lewison describes as a “transference” of emotions, anxieties, and interpretations.[2] This dynamic crystallizes in her groundbreaking series of seven pregnant nudes (1964–1978), a radical departure from Western art’s historical avoidance of the subject. Defying taboos that reduced the female body to erotic spectacle, Neel declared: “Modern painters have shied away because women were always done as sex objects. A pregnant woman has a claim staked out; she is not for sale” (ICA Boston, n.d., para. 2).[3] In “Margaret Evans Pregnant” (1978), this ethos manifests through deliberate tension: Evans sits with serene composure, her swollen body rendered in jagged, visceral brushstrokes. A fractured mirror behind her distorts her reflection, symbolizing societal erasure of maternal corporeality. Here, Neel channels Evans’ resolve and her own unresolved grief over her infant daughter’s 1927 death, transforming the nude from an object of desire to a site of lived transformation (see Fig. 1).[4]

Linda Nochlin’s Critique and Alice Neel’s Subversion of the Male Gaze

Neel’s portraiture confronts the historical male gaze[5] epitomized by Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” (1538) and Manet’s “Olympia”(1863) by reclaiming agency for her subjects.[6] Her unidealized nudes align with Linda Nochlin’s critique of the Western artistic tradition, which has historically objectified women, reducing their bodies to passive vessels for male fantasy. In her essay “Woman as Sexual Object”, Nochlin interrogates 19th-century erotic imagery, arguing that it perpetuates a one-dimensional perspective rooted in the “male gaze” a concept central to feminist critiques of visual culture. Published during the rise of second-wave feminism and its women’s liberation movements, Nochlin’s essay coincided with a broader cultural reckoning with gender and representation. While not explicitly activist, Neel’s work critically engaged with the tradition of nude representation, challenging its historical conventions and reclaiming agency for her subjects. Nochlin situates Neel’s practice within a lineage of women artists who, since the 1930s, have interrogated gender and sexuality from a distinctly female perspective, dismantling the patriarchal frameworks that have long dominated art history.[7]

Laura Mulvey’s Concept of the Gaze

In contrast to the “scopophilic gaze” theorized by Laura Mulvey (1975), in which women are objectified as passive objects of male desire within a patriarchal visual economy, Alice Neel’s portraiture disrupts this dynamic through a collaborative and dialogic process. Mulvey argues that classical cinema constructs the male viewer as the active bearer of the gaze, while reducing women to mere spectacles for visual consumption.[8] Neel, however, subverts this paradigm by engaging in hours of dialogue with her subjects, transforming portraiture into a practice of mutual recognition rather than objectification. Her work resists the voyeuristic and fetishistic tendencies of the male gaze, instead foregrounding the agency and subjectivity of her sitters. By centering their lived experiences and identities, Neel’s portraits challenge the power dynamics inherent in traditional visual representation, offering a radical reimagining of the relationship between artist, subject, and viewer.[9]

Documenting Marginality: Queer Identity and the Politics of Representation

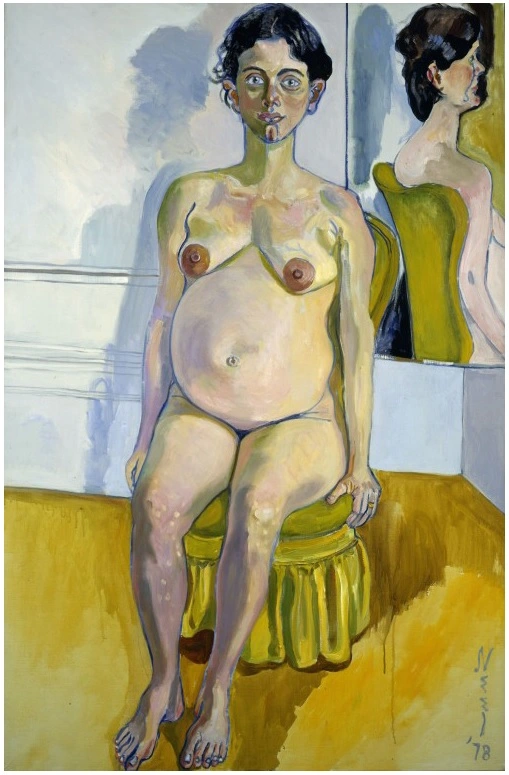

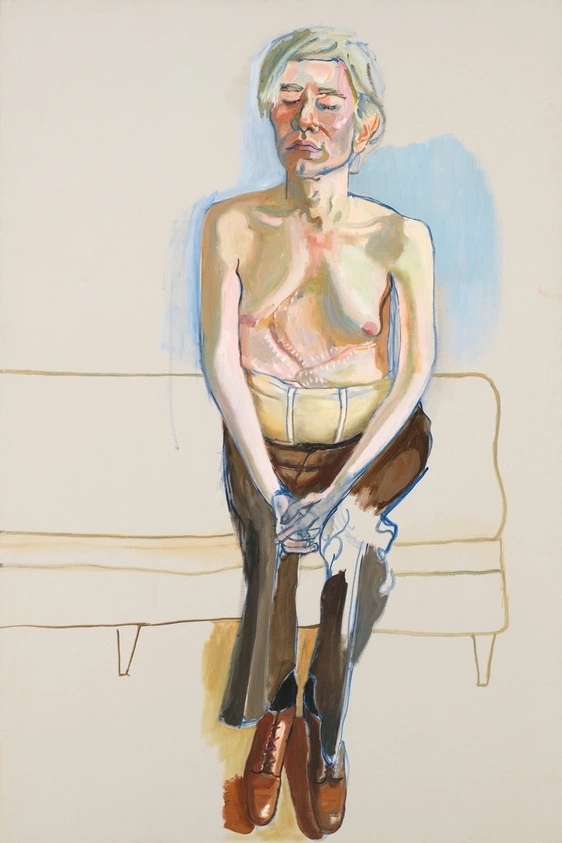

Fig. 2: Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970. oil and acrylic on linen.

Neel extended her humanist lens to queer figures, portraying them as fully realized individuals rather than symbols of difference. Her 1970 portrait of Andy Warhol subverts celebrity portraiture: shirtless and scarred from a 1968 assassination attempt, Warhol is depicted with a vulnerability rarely seen in public. In life, Warhol often concealed himself behind wigs, makeup, and sunglasses, maintaining a carefully cultivated air of indifference. He once stated, “Nudity is a threat to my existence” (Whitney Museum of American Art, n.d., para. 1). In Neel’s portrait, Warhol’s eyes close in meditative detachment, denying the viewer his iconic gaze. The canvas is dominated by cool tones, with a wash of soft blue encircling Warhol’s head and upper body, while his delicate, androgynous features are defined by Neel’s signature aquamarine hue (see Fig. 2).[10]

Defiance and Humanity: Neel’s Portrait of Faith Ringgold

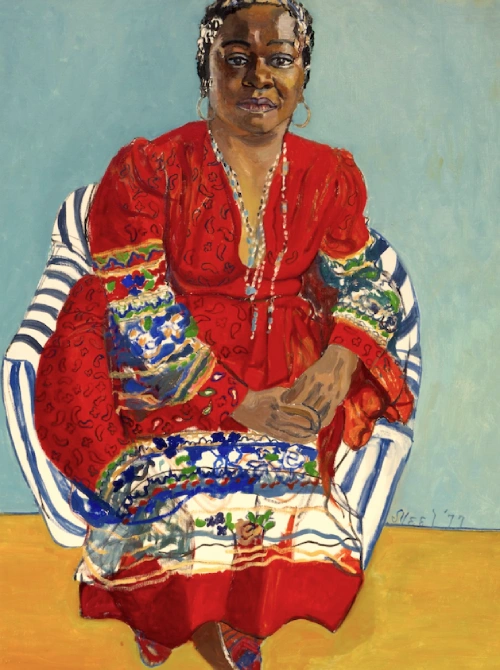

Fig. 3: Alice Neel, Faith Ringgold, 1977. Oil on canvas.

Similarly, Neel’s 1976 portrait of Faith Ringgold, the Black feminist artist, captures her staring defiantly, hands clasped, in a powerful and commanding pose. Ringgold posed for the portrait multiple times, and Neel depicts her wearing a red dress with a patterned skirt and sleeves, accessorized with beads in her hair and around her neck, along with hoop earrings (see Fig. 3). This portrait is a favorite of artist Jordan Casteel, who admires how Neel’s work “emulates and speaks and lusts out with a sense of humanity” that resonates with her own artistic journey. Casteel noted, “I feel Alice Neel in that painting. I feel her connection to Faith and her investment in Faith” (CultureType, 2019, para. 4).[10]

Defying Categories: Neel’s Ambivalent Feminism and Late Recognition

Alice Neel’s life and career defied gendered conventions, as she navigated societal barriers as a single mother and artist while rejecting the reductive label of “woman artist,” insisting instead on universal artistic merit. Her 1974 retrospective at the Whitney Museum marked a landmark moment for female artists, validating her decades of perseverance. Yet, Neel remained ambivalent toward formal feminist movements, even as later generations reclaimed her as a pioneering figure for her defiance of patriarchal norms and her unflinching portrayals of women’s lived realities. Her depictions of the female nude, informed by her lived experiences as a woman, mother, activist, and artist, reflect an expressive approach that transcends mere representation.[11] According to Pamela Allara, Neel’s nude paintings align with the ideological aims of the women’s movement, while her expressive style resonates with the corporeal explorations central to the Body Art movement.[12] By capturing the raw, unvarnished realities of her subjects, Neel’s work garnered significant attention from feminist critics, solidifying her position as a key figure in the discourse on gender and representation in art.[13]

Legacy and Continuity: Alice Neel’s Enduring Impact

Alice Neel’s oeuvre transcends the boundaries of portraiture, emerging as a radical archive of the 20th century’s social, political, and psychological fissures. Her work remains profoundly urgent today, as contemporary artists continue to grapple with themes of intersectional identity and bodily autonomy. Neel’s collaborative approach and her subversion of the male gaze prefigured modern discourses on agency and representation, while her unflinching focus on marginalized bodies challenges viewers to confront and resist societal erasure. As Neel herself declared, she painted “to try to reveal the struggle, tragedy, and joy of life” (Carroll, 2021, para. 1). By centering those whom history sought to erase, she ensured their stories and her own would endure as indelible marks on the canvas of art history.[14]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. Carroll, Jim, 2021. Alice Neel: Always in the Process of Becoming. [Accessed 14 March 2025].

2. Lewison, Jeremy. (2018). Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

3. ICA Boston. (n.d.). Margaret Evans Pregnant by Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Hasta St Andrews. (n.d.). Olympia by Édouard Manet. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

7. Vogel, Lisa. (1972) 'A review of Woman as Sex Object', Art Journal, 31(4), p. 384.

8. Mulvey, Laura. (1975) 'Visual pleasure and narrative cinema', Screen, 16(3), pp. 806–815.

9. Whitney Museum of American Art. (n.d.). Andy Warhol. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

10. Ibid

11.Culturetype (2019) A portrait of Faith Ringgold painted by Alice Neel is Jordan Casteel’s favorite artwork. (Accessed: 15 March 2025).

12. Lewison, Jeremy. (2018). Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

13. Allara, Pamela. (1998) Pictures of people: Alice Neel’s American portrait gallery. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press of New England, p. 7.

14. Lewison, Jeremy. (2018). Alice Neel. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

15. Carroll, Jim, 2021. Alice Neel: Always in the Process of Becoming. [Accessed 14 March 2025].

Image and Cover Image Sources:

Fig. 1: Alice Neel, Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas. Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Fig. 2: Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, 1970. Oil and acrylic on linen. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Fig. 3: Alice Neel, Faith Ringgold, 1977. Oil on canvas. Available via: CultureType. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).