Georgia O’Keeffe-Artistic Identity and Modernist Tensions

Section 1: The Stieglitz-O’Keeffe Conflict (1920–1929)

The tensions implicit in Stieglitz’s photographic project-his simultaneous celebration and containment of O’Keeffe’s genius-reached their breaking point between 1927 and 1935. Despite his manifesto-like declarations against “fuzzyism,” Stieglitz’s nude studies of O’Keeffe remained paradoxically aestheticized, their compositions creating emotional distance even as they purported to reveal intimate truths.[1]

Fig 1 (left): Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe with Matisse Bronze, 1921, palladium print,

sheet: 24.1 × 19 cm (9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in.), mount: 56.5 × 46.4 cm (22 1/4 × 18 1/4 in.).

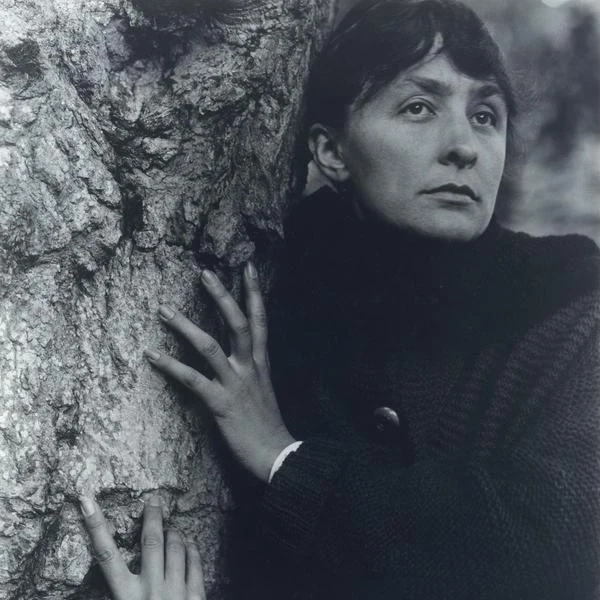

Fig 2 (right): Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe; a portrait, 1922, palladium print, 7 7/16 x 9 7/16 in (18.9 x 24 cm).

As public fascination with their artistic-personal partnership grew (fueled by exhibitions like the 1926 Seven Americans), O’Keeffe began strategically distancing herself from the “woman-child” persona Stieglitz had crafted. This section analyzes her defiance through pivotal developments: her increasing retreats to New Mexico and her ironic exploitation of the vaginal symbolism critics had imposed in her large-scale flower paintings. This growing resistance manifests visually in Stieglitz’s 1921 portrait (Fig. 1), where O’Keeffe clutches a Matisse bronze-originally exhibited at 291 as an exemplar of modernist primitivism with palpable discomfort. Matisse’s figurine, based on his study of African sculpture, now replaces the spoon as the signifier of O’Keeffe’s “primitive” identity. Yet this later staging diverges significantly: a sullen O’Keeffe, brow furrowed, looks away from the statuette, which she holds reluctantly, its presence a burden. Unlike earlier nude studies, she wears a plain white tunic, maintaining the dark/light dichotomy but stripping away the earlier photograph’s confessional intensity.[2]

Throughout the 1920s, Stieglitz’s portraits most frequently depicted O’Keeffe enveloped in dark clothing, her feminine attributes obscured-hair concealed beneath hats, her face often expressing sadness or melancholy (Fig. 2). Counter to these severe images, Stieglitz persisted in framing her work through an eroticized, Freudian lens, reinforcing the sensationalism of his 1921 exhibition.[3] As O’Keeffe endured recurring illnesses and critical scrutiny, she suffered silently, hoping the unwanted erotic interpretations would fade.[4] Her painterly reinventions from 1923 to 1933 provided novelty while covertly subverting the “woman-child” trope. In these formal shifts, we see O’Keeffe excising sexual performativity from her identity as modernism’s feminine archetype.[5]

Section 2: Formal Experimentation and Spatial Innovation (1920–1929)

Fig 3: Georgia O'Keeffe, Red, Yellow and Black Streak, 1924, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 31 3/4 in (100 x 80.6 cm).

Fig 4: Georgia O'Keeffe, Grey, Blue and Black- Pink Circle, 1929, oil on canvas, 36 × 48 in (91.4 × 121.9 cm).

O’Keeffe developed motifs serially, manipulating color and form to explore expressive possibilities. Her adjustment of the pictorial frame-mimicking a camera lens-alternately expanded or contracted spatial relationships, destabilizing viewer expectations. In 1920s canvases, she shifted perspectives radically: gazing upward at sky and trees, downward at the ground, or spinning laterally as if turning in place. These spatial experiments subverted traditional landscape horizontality, rendering Lake George as a panorama of sheer energies (Fig. 3).[6]

By the late 1920s, her edges dissolved into fluttering floral movements, exhausting the lyrical line as a language of femininity. The abstract spirals of 1915, which O’Keeffe had reinvented as expressions of interiority, now emerged organically in nature. In Grey Blue and Black-Pink Circle (Fig. 4), the spiral evokes the magic of a kachina doll, its vortex drawing the viewer’s eye into a swirling rhythm. This bodily engagement where viewers feel engulfed by the painting’s movement-is central to her work’s impact.[7]

Section 3: Floral Imagery and Critical Reception (1920s–1930s)

In the 1920s, Georgia O’Keeffe began her iconic exploration of floral imagery-a subject that crystallized her central artistic concerns. While flowers had traditionally been relegated to the domain of amateur female painters, O’Keeffe radically redefined them, rendering petals that strained against the canvas edges and magnifying their reproductive anatomy with an almost confrontational intensity. Her use of vivid, saturated hues which she provocatively termed "magnificently vulgar" further disrupted conventional expectations.[8]

This bold approach invited highly gendered interpretations from contemporary critics. Paul Rosenfeld, for instance, framed her abstractions as revelations of "feminine sexuality’s mystery," while Henry McBride famously labeled her a "priestess of mystery" in 1927. Similarly, Louis Kalonyme asserted in 1928 that O’Keeffe’s work stripped away civilization’s constructed femininity to expose a primal, "natural" essence. Such readings, however, often conflated her art with essentialist notions of womanhood-a reduction O’Keeffe vehemently resisted.[9]

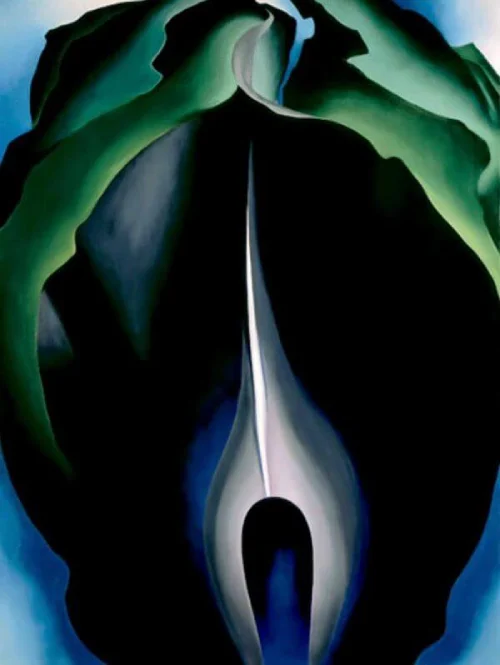

Fig 5: Georgia O’Keeffe, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV, 1930, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 in (101.6 × 76.2 cm).

Among her most significant floral works, the Jack-in-the-Pulpit series (comprising six paintings of varying scales) exemplifies her subversion of both botanical and gendered conventions. The sequence progresses from an external view of the flower to an almost microscopic examination of its stamens and pistils. The painting (fig. 5) epitomizes O’Keeffe’s manipulation of scale and spatial ambiguity: the flower’s interior dominates the composition, blurring distinctions between interior and exterior, mass and void. Deep blue voids at the canvas corners envelop the central form, while the inky blackness of the petal’s core suggests an abyss penetrated by a flame-like protrusion. The pistil’s form oscillates between phallic solidity and cavernous depth, destabilizing fixed interpretations.[10]

These formal ambiguities mirror the androgynous duality of O’Keeffe’s imagery, which defies simplistic gendered readings. She rejected critics’ insistence on a "feminine" symbolism, arguing that such interpretations obscured her work’s broader metaphorical dimensions-its interplay between body, nature, and landscape. For O’Keeffe, metaphor was not merely stylistic but epistemological, a means of understanding one reality through another. The Jack-in-the-Pulpit series, like her finest works, invites viewers to re-examine the familiar through this destabilizing lens.[11]

Section 4: American Identity and Late Career (1930–1972)

New York to New Mexico: Shifting Perspectives (1925–1930s)

In 1925, after her marriage to Stieglitz, the couple moved into the Shelton Hotel’s upper floors, where O’Keeffe began her iconic series of New York city spaces and skyscrapers. These works functioned as a subversive, gender-bending project, asserting her autonomy within the male-dominated modernist movement (Fig. 6). By 1929, her artistic trajectory shifted dramatically when she accepted an invitation from Mabel Dodge, the famed patron of the New York avant-garde, to visit New Mexico. The region’s stark landscapes ignited a profound connection, marking the birth of the “O’Keeffe myth” and her enduring association with the American Southwest.[12]

Fig 6: Georgia O'Keeffe, The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y., 1926,

oil on canvas, 122.6 × 76.9 cm (48 1/4 × 30 1/4 in.).

In 1925, after her marriage to Stieglitz, the couple moved into the Shelton Hotel’s upper floors, where O’Keeffe began her iconic series of New York cityscapes and skyscrapers. These works functioned as a subversive, gender-bending project, asserting her autonomy within the male-dominated modernist movement (Fig. 6). By 1929, her artistic trajectory shifted dramatically when she accepted an invitation from Mabel Dodge, the famed patron of the New York avant-garde, to visit New Mexico. The region’s stark landscapes ignited a profound connection, marking the birth of the “O’Keeffe myth” and her enduring association with the American Southwest.[12]

Fig 7: Georgia O'Keeffe, Gerald's Tree I, 1937, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 1/8 in (101.6 × 76.5 cm).

Challenging American Narratives (1930s–1940s)

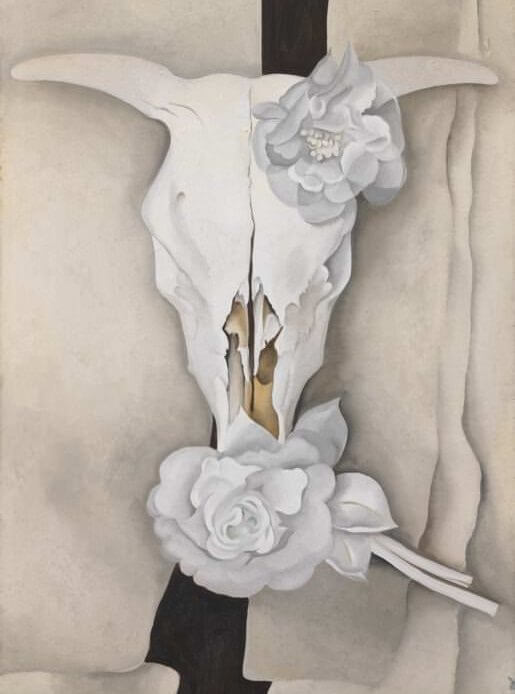

Fig 8: Georgia O'Keeffe, Cow's Skull with Calico Roses, 1931, oil on canvas, 91.4 × 61 cm (36 × 24 in.).

O’Keeffe’s engagement with American identity directly contested the era’s prevailing artistic narratives. While Eastern peers romanticized the “American scene” through clichéd depictions of farmsteads and livestock, her firsthand immersion in the Southwest exposed the artifice of such urban projections.[14] During the 1930s cultural nationalist debates, she redefined Southwestern iconography: pelvic bones framing azure voids and rams’ skulls hovering above eroded mesas became both earnest explorations and sly critiques of nativist expectations.[15] Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses, 1931(Fig. 8), epitomized her vision-an America distilled to its essence, far beyond urban confines.[16]

Fig 9: Georgia O'Keeffe, Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow, 1945,

oil on canvas, 36 × 48 in (91.4 × 121.9 cm).

Her hardened, sun-bleached palette reached its zenith in the Pelvis Series (1940s), where animal bones framed desert skies as portals to cosmic infinity (Fig. 9). As she wrote to Anita Pollitzer in 1944: “The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive in the desert even though it is vast and empty” (O’Keeffe, 1987, p. 211).[17]

Late Radicalism and Legacy (1940s–1972)

O’Keeffe’s late career saw two radical departures:

The Black Place landscapes (1940s–50s): Geological forms dissolved into undulating waves of gray and pink, echoing her floral abstractions but with geologic austerity.

The Sky Above Clouds murals (1965–67): Painted at nearly 80 years old, these 24-foot canvases abandoned terrestrial perspectives entirely, merging Minimalist repetition with her lifelong pursuit of essential forms.[18]

Even as macular degeneration left her legally blind by 1972, O’Keeffe continued producing stark charcoal abstractions, paradoxically returning to the reductive language of her 1915 works. This full-circle journey-from abstraction to representation and back-cemented her legacy as a relentless innovator across six decades.[19]

Section 5: The Legacy of Georgia O’Keeffe

O’Keeffe resisted being labeled a woman artist, yet her work transcended this category entirely. By distilling the natural world into abstracted forms, she created enduring symbols woven into the mythology of American art. Today, the majority of her oeuvre is preserved by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, a testament to her cultural permanence.[20]

Though her popularity waned mid-century, the 1970 Whitney Museum retrospective reignited public fascination, aligning her legacy with the era’s feminist movement. By 84, her central vision had failed, yet she continued painting and persisted in producing watercolors, pencil sketches, and clay works. Her final works, reduced to essential abstract lines, echoed the radical simplicity of her 1915 charcoals, completing a circular artistic journey.[21]

Over seven decades, O’Keeffe shaped American modernism as a central figure in the Stieglitz Circle while defying gendered constraints. Though she rejected explicit feminist readings of her flower paintings, artists like Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro drew inspiration from their perceived feminine iconography. With over 2,000 works, her prolific output cemented her as a pioneering force. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, the first U.S. institution dedicated to a female artist, underscores her monumental impact, fostering scholarship through its research center and fellowships.[22]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1.Stieglitz, Alfred. (1926) [Letter to Herbert Seligmann, 22 February 1926]. In: Seligmann, H.J. (1966) Alfred Stieglitz Talking. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 61-62.

2. Cauman, John. (2001) 'Henri Matisse, 1908, 1910, and 1912: New evidence of life'. In: Greenough, S. et al. Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries. Washington: National Gallery of Art, p. 93.

3. Epstein, Daniel Mark (2001) What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. New York: Henry Holt and Company, p. 135.

4. James, Rebecca Salsbury (1963) [Letter to Georgia O'Keeffe], 6 September 1963. Georgia O'Keeffe Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL), Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

5. Oaks, Gladys (1930) 'Radical writer and woman artist clash on propaganda and its uses', New York World, 16 March, Women's section, pp.1, 3.

6. O'Brien, Frances (1920s) [Interview notes with Georgia O'Keeffe], unpublished manuscript, pp.5, 18.

7.Kalonyme, Louis (1929) 'Georgia O'Keeffe', [Introduction to exhibition catalog]. Intimate Gallery, New York, pp. xxxiv-xl. Reprinted in: Lynes, Barbara Buhler (1999) Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: The Passionate Eye, pp.278-282.

8.Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American Encounters: Art History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

9. McBride, Henry (1929) 'Paintings by Georgia O'Keeffe: Decorative art that is also occult', New York Sun, 9 February, p.7. Reprinted in: Lynes, Barbara Buhler (1999) Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: The Passionate Eye, pp.295-296.

10. Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American Encounters: Art History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Pyne, Kathleen A. (1999) 'The Promise and the Burden of the Work of Art: Georgia O'Keeffe', in Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries, edited by Sarah Greenough. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, p. 265. [Online] (Accessed: 8 April 2025).

14. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (n.d.) The Horse’s Skull on Blue (1930) [Online]. (Accessed: 2 April 2025).

15. Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American Encounters: Art History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

16. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (n.d.) The Horse’s Skull on Blue (1930) [Online]. (Accessed: 2 April 2025).

17. O'Keeffe, Georgia. Georgia O'Keeffe: Art and Letters. Edited by Jack Cowart, Juan Hamilton, and Sarah Greenough, National Gallery of Art, 1987, p. 211.

18. The Art Story Foundation (n.d.) Georgia O'Keeffe: Biography and Legacy [Online].(Accessed: 2 April 2025).

19. Ibid.

20. WikiArt (n.d.) Georgia O'Keeffe [Online]. (Accessed: 2 April 2025).

21. The Art Story Foundation (n.d.) Georgia O'Keeffe: Biography and Legacy [Online]. (Accessed: 2 April 2025).

22. Ibid.

Images Sources:

Fig 1 Source: NGA.

Fig 2 Source: Imago Images

Fig 3 Source: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections

Fig 4 source: Artsy

Fig 5 source: Artchive

Fig 6 Source: Art Institute of Chicago

Fig 7 Source: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections

Fig 8 source: Georgia O'Keeffe Online

Fig 9 Source: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections

Image Cover Resource:

Herman Miller (2023) New Mexico Collection [Photograph]. (Accessed: 2 April 2025).