Georgia O’Keeffe and the Struggle for Artistic Identity

Section 1: The Making of an American Modernist (1887–1918)

Academic Foundations and the Rejection of Tonalism

Georgia O’Keeffe’s early artistic development (1887–1915) was characterized by a gradual departure from conventional representation toward an instinctive yet disciplined modernism, shaped by her academic training, intellectual curiosity, and the vast American landscape. Born in Wisconsin, she came of age during the decline of genteel artistic traditions, witnessing the shift from Tonalism with its softened contours, muted palettes, and atmospheric obscurity toward a more incisive and individualized mode of perception. Her formal education began at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and continued at New York’s Art Students’ League under William Merritt Chase (1849–1916). Though she later admired Chase, O’Keeffe initially emulated his painterly approach, which prioritized fleeting optical effects of light and shadow a method she ultimately rejected in favor of abstraction.[1]

The 1915 Breakthrough: Dow’s Musical Pedagogy and Abstraction

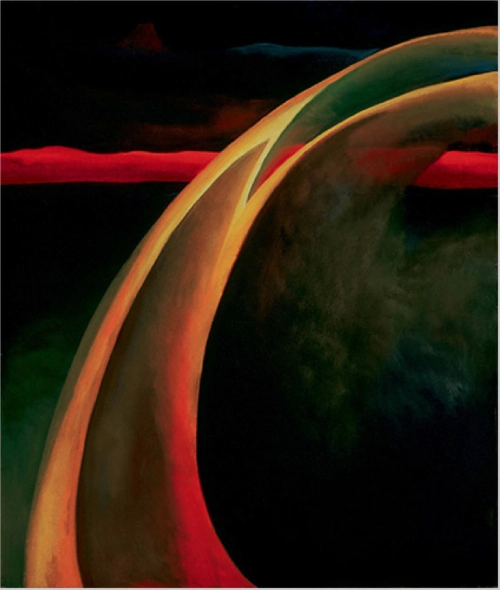

A pivotal transformation occurred in 1915 while teaching in the expansive terrain of the western Plains, where she synthesized diverse influences into a radically abstract style. Under Arthur Wesley Dow’s tutelage at Columbia Teachers College, O’Keeffe learned to visualize abstract forms through musical rhythms, a pedagogical approach that profoundly shaped her practice. By the late 1910s, she began transposing auditory experiences such as the resonant calls of cattle at dusk into vivid visual forms, exemplified in works like Red and Orange Streak (fig. 1), where the horizon erupts in chromatic intensity. Despite her insistence that her art emerged solely from personal experience, O’Keeffe engaged deeply with contemporary intellectual currents, including literature, philosophy, and avant-garde criticism. Her exposure to Camera Work connected her to modernist discourse, and her rejection of traditional conventions became an assertion of autonomy. As she later asserted, constrained by the limited freedoms afforded to women, she resolved to define her own artistic parameters.[2]

Fig. 1: Georgia O'Keeffe, Red and Orange Streak, 1919,

Oil on canvas, 27 × 23 inches (68.6cm × 58.4 cm).

The 1917–1918 Watercolors: Childlike Vision as Radical Practice

Upon returning to New York in 1917, O’Keeffe entered into a lifelong professional and personal partnership with Alfred Stieglitz, a relationship that endured until his death in 1946. This alliance with modernism’s foremost promoter exposed her to new influences through the male-dominated circle of artists associated with Gallery 291, further shaping her evolving practice.[3] A series of watercolors from this period (1917–18) demonstrates O’Keeffe’s deliberate engagement with the medium’s inherent unpredictability such as uneven transparency, pigment bleeding, and textural ridges alongside an intentional evocation of naïve draftsmanship.[4] Here, her approach reflects a studied emulation of the selective forms and simplified gestures characteristic of children’s art. Rather than adopting conventional juvenile motifs (e.g., houses, chickens), she internalized the schematizing logic of a child’s visual language to articulate her own sense of awe while confronting the vast Texan landscape under starlit skies. [5]

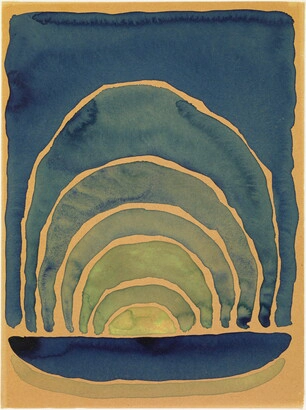

This sensibility is particularly evident in her deployment of the spiral motif within the Evening Star watercolors (fig. 2) and the Light Coming on the Plains (fig. 3) series, where the tremulous quality of line suggests the unsteady hand of a child. The rhythmic brushwork, akin to the arcing motion of a child drawing a rainbow, transmutes celestial energies into visual cadences.[6] Unlike Kandinsky, who embraced the unrestrained aesthetic of preschool scribbles, O’Keeffe negotiated a balance between childlike simplicity and formal precision a synthesis informed by Dow’s Japanese-derived principles of decorative spatial composition. These works not only anticipate her later return to representation after another abstract phase but also coincide with her first year cohabiting with Stieglitz.[7]

Fig. 2: Georgia O'Keeffe, 1917, Evening Star No. IV, 1917،

Watercolor on paper, 8⅞ × 12 inches (22.5 × 30.5 cm).

Fig. 3: Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986), The Light Coming on the Plains, No. I, 1917,

watercolor on paper (mounted on newsprint), 8⅞ × 11⅞ inches (22.5 × 30.2 cm).

Section 2: Stieglitz’s Photographic Framing (1917–1925)

The "Great American Sexquake": Freudian Readings of Modernist Art

The Stieglitz circle’s engagement with early 20th-century sexual liberation movements was inextricable from their artistic praxis. As Benjamin de Casseres proclaimed, the "Great American Sexquake" of the 1910s–1920s reframed sexuality as a sacramental force against Puritanical repression.[8] This discourse permeated the criticism of Paul Rosenfeld, who eroticized the works of Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe through a Freudian lens. Dove’s abstractions were lauded for their "tremendous muscular tension" and "male vitality," while O’Keeffe’s paintings were reductively interpreted as expositions of "women’s sexual feelings".[9] Stieglitz amplified these readings through his 1921 exhibition of nude photographic studies depicting O’Keeffe in post-coital states images that transformed her body into a public spectacle "Naked on Broadway" and her art into a marketable extension of her sexuality.[10]

The Woman-Child Paradigm: Stieglitz’s Essentialist Vision

Stieglitz’s 1919 essay Woman in Art codified his essentialist vision of O’Keeffe as the archetypal woman-child, whose creativity emanated from the womb as the "seat of her deepest feeling".[11] This construct, indebted to Havelock Ellis’s theories of feminine infantilization and Freud’s On Narcissism (1914), positioned O’Keeffe’s art as a primal, preverbal expression of the "unconscious body".[12] Stieglitz's photographic portraits (1917-1935) visually reinforced this narrative. In (fig. 4), O'Keeffe appears with her long hair flowing over bare shoulders as she stretches her arms upward, connecting her fingers to the elongated lines that spiral rhythmically toward the frame's top edge. These compositions reflect the influence of Anne Brigman's dancing nudes, whose bodies merged poetically with natural forms a visual language that taught Stieglitz how to make O'Keeffe's body articulate its latent sexual truths.[13]

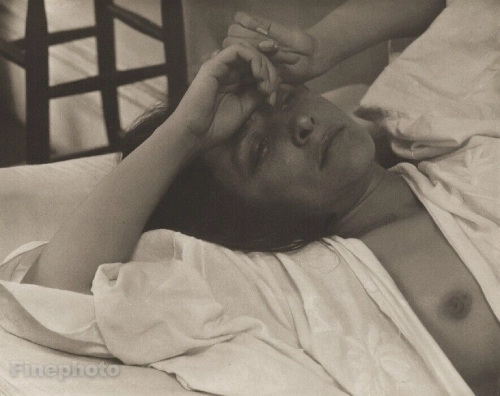

Fig 4: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe (Nude No. 8), 1918,

palladium print, 7⅛ × 9 inches (18.1 × 22.9 cm).

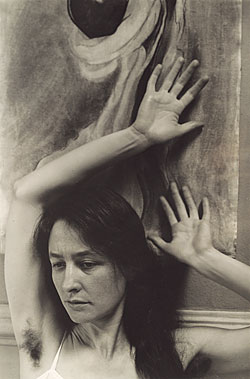

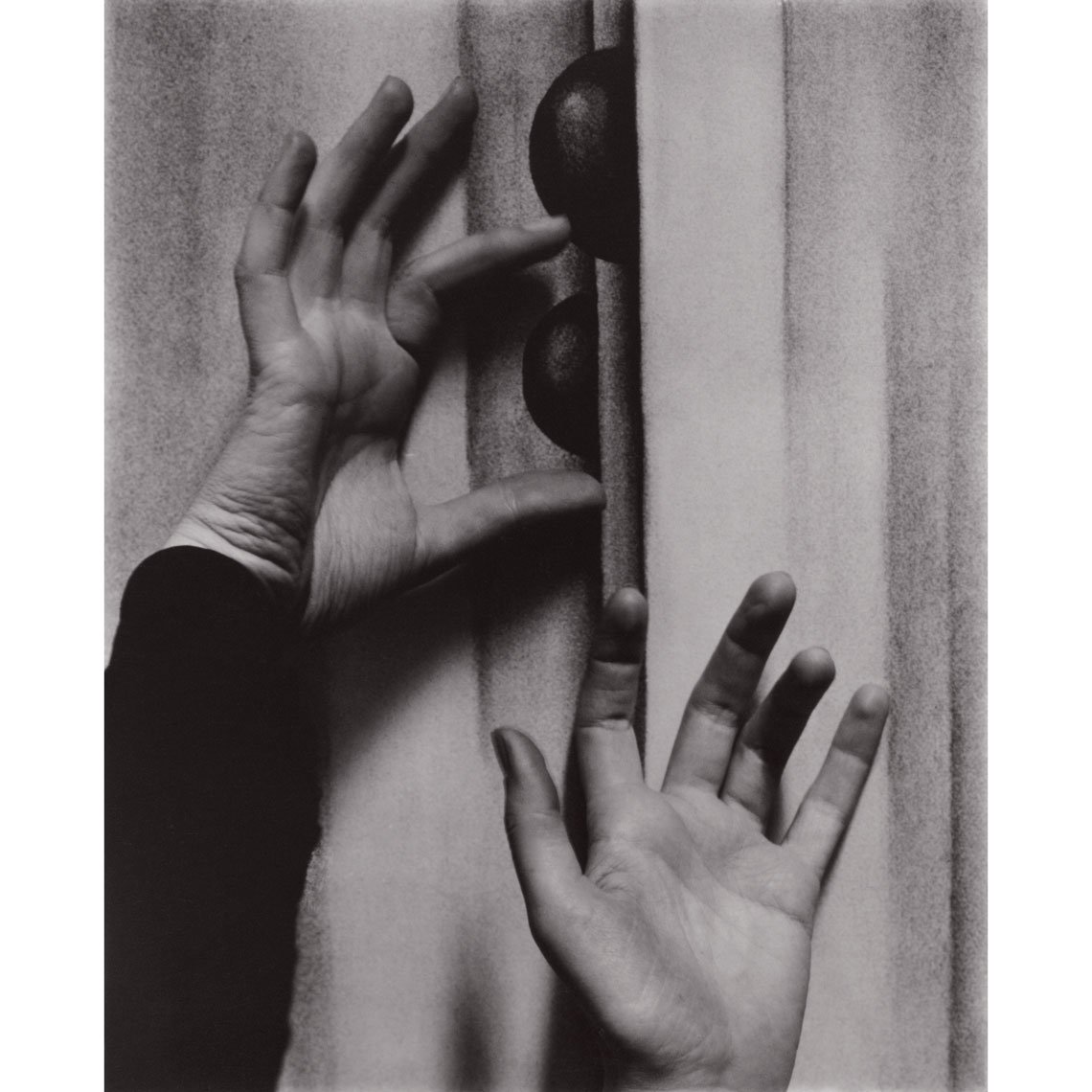

The earlier 1917-1918 portraits focused on O'Keeffe's hands, with their distinctive elongated fingers arranged against her artworks, suggesting the artist magically conjuring her images into being (Fig. 5).[14] The later works instead position O'Keeffe-as-Lover performing a choreographed dance that manifests her maternal relationship to her creations, particularly through compositions where her extended arms and fingers visually merge with the flowing lines of the paper itself. O’Keeffe’s hands merge with her abstract paintings, embodying his belief that her works were "paint-babies" birthed from somatic intuition rather than intellectual labor.[15]

Fig. 5: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe in Gallery 291, 1918,

silver gelatin print, 19 × 23.9 cm (6¹⁄₁₆ × 9¼ inches).

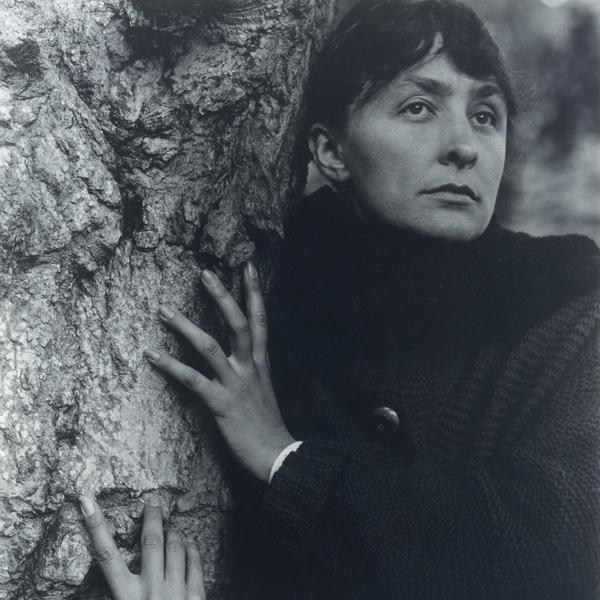

Anne Brigman’s Legacy and the Limits of Agency

Stieglitz’s photographic staging of O’Keeffe was deeply informed by his earlier work with Anne Brigman, whose wilderness nudes pioneered the conflation of female creativity with organic forms. His 1918 portraits of O’Keeffe, maternal sexuality as natural (see Fig. 6) replicated Brigman’s visual syntax: twisted limbs against an ancient gnarled tree at Lake George, spiraling gestures mirroring abstract compositions. However, where Brigman asserted agency as both artist and subject, Stieglitz reduced O’Keeffe to a mediated image a "universal woman-child" whose pain and primitivism were aestheticized for public consumption.[16]

Fig. 6: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe at 291, 1917,

silver-platinum print, 19 × 23.9 cm (7½ × 9⁷⁄₁₆ inches).

Section 3: O’Keeffe’s Subversions and the Stieglitz Circle’s Contradictions

Strategic Complicity: The "Phallic Woman" and Editorial Control

Recent scholarship complicates narratives of O’Keeffe as a passive victim. Her strategic collaboration with Rosenfeld (editing his 1924 Port of New York) and her manipulation of phallic imagery such as holding Abstraction phallic sculpture, Hands1919, (Fig. 7), where she "fondles the genitals of the photographer" reveal her tactical engagement with gendered constructs As Marcia Brennan argues, O’Keeffe became the "phallic woman" who repurposed masculine tropes to assert artistic autonomy.[17]

Fig. 7: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe - Hands, ca. 1919.

Gelatin silver print, 7 1/2 × 9 7/16 inches (19 × 24 cm).

Gendered Double Standards in Critical Reception

The circle’s critical apparatus applied divergent standards to male artists: Dove’s abstractions were celebrated as both "embryonic" and "phallic," while John Marin’s works were praised for their "fluid and phallic" duality. In contrast, Hartley and Demuth both gay faced homophobic readings of their art as "effeminate" or "depraved", exposing the limits of the circle’s progressive veneer.[18]

Toward Part II –The Breaking Point (1927-935)

While Stieglitz’s early portraits (1917–1925) established O’Keeffe as modernism’s eroticized archetype, his later images produced amid growing public scrutiny (1927–1935) would amplify their contentious dynamic. Part II examines how O’Keeffe navigated these controversies, reclaiming agency through her later work in New Mexico as Stieglitz’s mythmaking collided with her defiant reinvention.[19]

Essay by Malihe Norouzi

References:

1. Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American Encounters: : Art History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. O'Keeffe, Georgia. (1916) [Letters to Alfred Stieglitz], 11 and 18 September 1916. In: Cowart, J., Hamilton, J. and Greenough, S. (eds.) Georgia O'Keeffe: Art and Letters. Washington: National Gallery of Art, pp. 156-157

6. Gardner, Howard. (1980) Artful Scribbles: The Significance of Children's Drawings. New York: Basic Books, pp. 137-149.

7. Lowe, Sue. Davidson. (1983) Stieglitz: A Memoir Biography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 230.

8. Miller, Angela, Berlo, Janet Catherine, Wolf, Bryan & Roberts, Jennifer (2024) 'The arts confront the new century: renewal and continuity (1900-1920)', in American EncountersArt History and Cultural Identity. LibreTexts, pp. 407-411. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Stieglitz, Alfred. (1973) 'Woman in art', in Norman, D. Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer. New York: Aperture, pp. 36-38.

12. Freud, Sigmund. (1914) 'On narcissism: an introduction', in Strachey, J. (ed. and trans.) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 14: 1914-1916. London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis, pp. 73-104.

13. Stieglitz, Alfred. [1918] [Letter to Anne Brigman, early 1918]. Alfred Stieglitz Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL), Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Written while working in the attic room above "291" gallery, sorting art and publications.

14. Seligmann, Herbert. J. (1966) Alfred Stieglitz Talking. New Haven: Yale University Press.

15. Weaver, Mike. (1996) 'Alfred Stieglitz and Ernest Bloch: Art and hypnosis', History of Photography, 20(4), pp. 293–303.

16. Stieglitz, Alfred. [1918] [Letter to Anne Brigman, early 1918]. Alfred Stieglitz Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature (YCAL), Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Written while working in the attic room above "291" gallery, sorting art and publications.

17. Brennan, Marcia. Greenough, Sara. & Peters, Sarah. Whitaker. (2000) ‘[Review of Painting Gender, Constructing Theory by Marcia Brennan; Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries by Sarah Greenough; Becoming O'Keeffe by Sarah Whitaker Peters]’, Archives of American Art Journal, [online] p. 37. (Accessed: 1 April 2025).

18. Ibid.

19. Stieglitz, Alfred. (1926) [Letter to Herbert Seligmann, 22 February 1926]. In: Seligmann, H.J. (1966) Alfred Stieglitz Talking. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 61-62.

Images sources:

Fig.1 source: View artwork

Fig.2 source: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections

Fig.3 source: Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Collections

Fig.4 source: View details

Fig.5 source: linneawest.com

Fig.6 source: NGA Collection Online

Fig.7 source: InCollect