The Unsettling Beauty of Yayoi Kusama’s Erotic Art

Kusama's Provocative Vision

Yayoi Kusama (1929), the Japanese avant-garde artist, has captivated the art world for decades with her bold, immersive, and often provocative creations. Known for her iconic polka dots and infinity rooms, Kusama’s work transcends traditional boundaries, blending art, performance, and psychology into a singular vision.[1] While her installations and paintings have garnered widespread acclaim, her sculptures particularly those exploring controversial themes remain a lesser-discussed yet vital aspect of her oeuvre.[2] These works, often characterized by their phallic forms and visceral textures, challenge societal taboos and invite viewers to confront their own perceptions of sexuality, obsession, and the human body.[3]

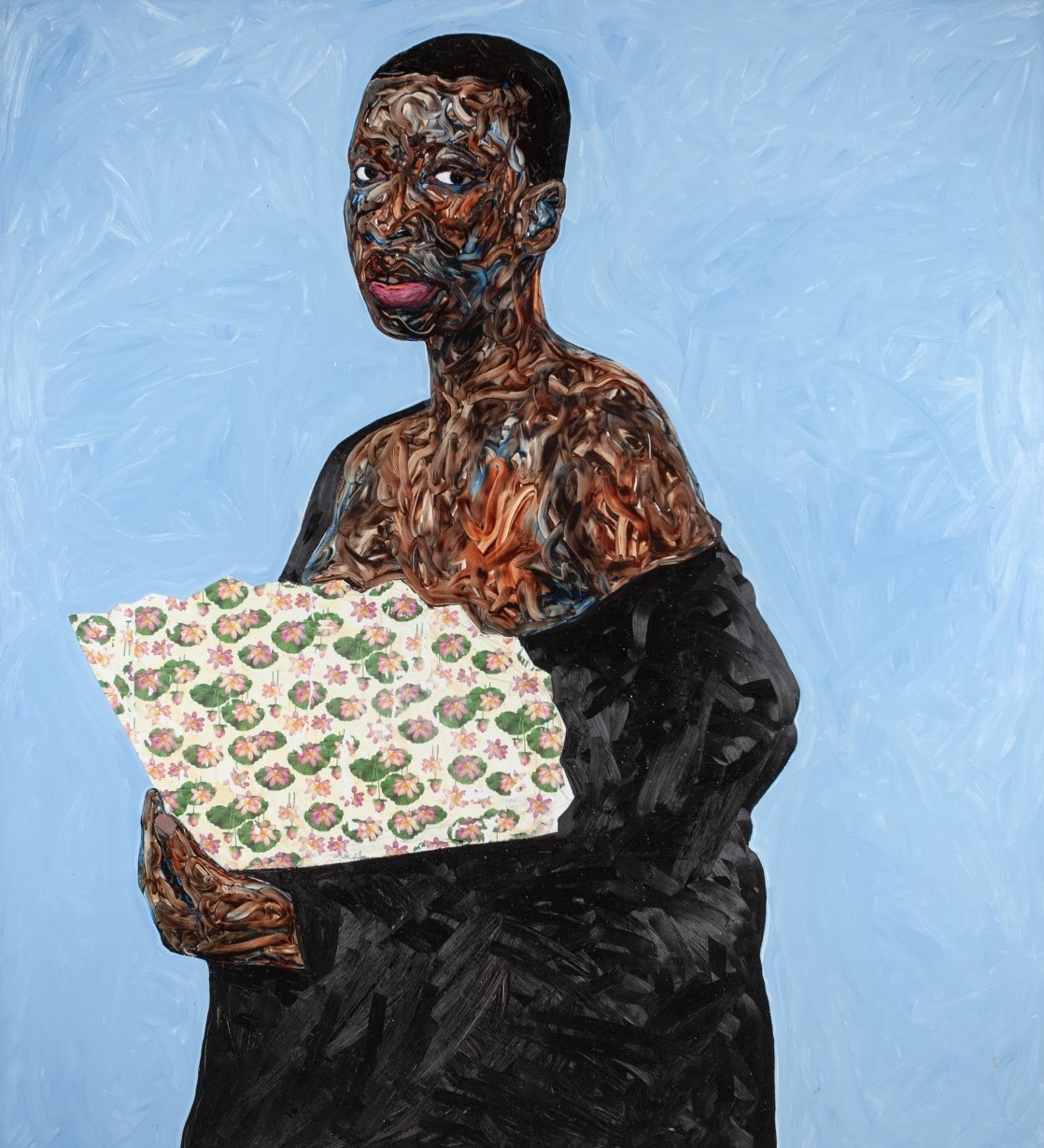

1. Yayoi Kusama, The Armchair from Accumulation No.1, 1962

Sex, Obsession, and Phallic Forms

Emerging in the 1960s during a time of cultural upheaval and sexual liberation, Kusama’s sculptures reflect her personal struggles with mental health, particularly her obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and her defiance of patriarchal norms. Through her art, she transforms vulnerability into power, using the body as a site of both rebellion and healing. This article delves into Kusama’s most erotic sculpture project, “The Armchair” piece, examining how it redefines the boundaries of art, challenges societal expectations, and continues to resonate in contemporary discourse.[4]

The Armchair: Domestic Object Transformed

The Armchair piece, part of Kusama’s Accumulation series, is one of her most provocative and iconic bodies of work. Created in the 1960s, this series prominently features phallic imagery, a recurring motif in Kusama’s art. The Armchair transforms a mundane household object into a surreal, almost grotesque sculpture by covering it with countless soft, fabric protrusions resembling phallic forms. This juxtaposition of the familiar and the unsettling forces viewers to grapple with their own discomfort and curiosity. [5]

Psychological Roots: Art as Therapy

Kusama’s use of phallic forms in The Armchair was deeply influenced by her childhood experiences with sexuality and her struggles with mental health. As she explains in her autobiography, Infinity Net, “I was fighting pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and the only method I had to cure my illness was to keep creating art” (Kusama, cited in Improvised Life, 2013).[6] Through the repetitive use of phallic motifs, Kusama blurs the boundaries between obsession and compulsion, as well as attraction and repulsion. This tension mirrors her personal experiences with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and her ongoing effort to confront and reclaim control over her fears. As Kusama herself explained, she “began making penises in order to heal her feelings of disgust towards sex. Reproducing the objects…was her way of conquering the fear” (Kusama, cited in Museum of Modern Art, n.d.). By transforming a mundane domestic object into something simultaneously erotic and unsettling, Kusama compels viewers to engage with their own discomfort regarding themes of sexuality and the human body. This interplay between the personal and the universal underscores the psychological and emotional depth of her work.[7]

Tactile Duality: The Abject and Alluring

Kusama’s use of soft, domestic materials creates a tactile, body-like quality that invites touch while simultaneously provoking unease.[8] This duality aligns with Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection, as outlined in her 1980 book Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Kristeva describes abjection as the psychological state of being simultaneously repelled and fascinated by something that disturbs the boundaries between the self and the other, often involving themes of the body, decay, and taboo.[9] In Kusama’s work, the phallic forms both familiar and grotesque embody this tension, challenging viewers to confront their own discomfort with the boundaries of the human body and societal norms.[10]

Between Minimalism and Post-Minimalism

Kusama’s Accumulation series occupies a fascinating intersection between her practice and the emerging Minimalist movement. These works, composed of ready-made furniture covered in small, sewn protuberances. The repetitive patterns, previously confined to the canvas, now extend into three-dimensional space, enveloping everyday objects. Metaphorically, the protrusions are often interpreted as phallic forms, reflecting Kusama’s confrontation with her own sexual anxieties. Yet, beyond their psychological resonance, the series also challenges viewers through its sheer physical presence. Kusama’s relationship with Minimalism is complex and often contradictory. While her Accumulation series shares Minimalism’s emphasis on repetition and seriality, her approach diverges significantly in tone and intent. Donald Judd’s seminal essay Specific Objects (1965) notably overlooks the psychoanalytic dimensions of Kusama’s work, describing her sculptures merely as “strange objects.” [11]

Beyond Minimalism: The Personal in Repetition

Robert Morris’s Notes on Sculpture (1966), a key theoretical contribution to Minimalism, further develops Judd’s ideas through a phenomenological lens, emphasizing the viewer’s bodily engagement with art. Yet, Kusama’s work resists such detached analysis; her accumulations are intensely personal, imbued with sensuality and humor qualities largely absent from the austere geometries of Minimalist contemporaries like Frank Stella or Ad Reinhardt. [12]

Legacy and Influence: Post-Minimalist Connections

Kusama’s practice also aligns with, and diverges from, the concerns of Post-Minimalism. While Minimalism often evokes industrial production and impersonal systems, Kusama’s repetition serves a more intimate, therapeutic function. Her obsessive, labor-intensive process destabilizes the modernist obsession with novelty, even as she pushes the boundaries of aesthetic innovation. This tension complicates linear narratives of art history, situating her work in dialogue with both Minimalism and its aftermath. Her connections to Post-Minimalist artists like Eva Hesse and Carolee Schneemann further underscore her influence. Like Hesse, Kusama explores the organic and the absurd, while her participatory performances echo Schneemann’s confrontational approach to the body and gender.

At the same time, her contributions to American Pop art and European concrete art have cemented her legacy as a pivotal figure in 20th-century art. While her Accumulation series offers a compelling lens through which to examine her relationship with Minimalism and Post-Minimalism, Kusama’s enduring relevance lies in her ability to continually produce work that challenges, captivates, and transcends artistic boundaries. [13]

Essay by malihe Norouzi / Independent Art Scholar

References:

1. The Art of Zen, 'Yayoi Kusama: A Polka-Dotted Revolution in Art', The Art of Zen, accessed 15 October 2023.

2. Artdex, 'Obsessed with Dots: Yayoi Kusama’s Endless Exploration of Infinity', Artdex, accessed 15 October 2023.

3. Masterworks Insights, 'Understanding Sexuality in Yayoi Kusama’s Art', Masterworks Insights, accessed 15 October 2023.

4. Artsy Editorial, '6 Works That Explain Yayoi Kusama’s Rise to Art Stardom', Artsy, accessed 10 October 2023.

5. Kusama, Yayoi, Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away (2013), mixed media, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), accessed 15 October 2023.

6. Improvised Life, 'Yayoi Kusama’s Life of Innovating and Reinventing', Improvised Life, 21 November 2013, accessed 18 February 2025.

7. Museum of Modern Art, “Yayoi Kusama. The Armchair,” MoMA, n.d., accessed 20 February 2025.

8. Masterworks Insights, 'Understanding Sexuality in Yayoi Kusama’s Art', Masterworks Insights, accessed 15 October 2023.

9. Kristeva, Julia, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), pp. 1-6.

10. Masterworks Insights, 'Understanding Sexuality in Yayoi Kusama’s Art', Masterworks Insights, accessed 15 October 2023.

11. Judd, Donald, ‘Specific Objects’, Art Yearbook 8 (1965), reprinted in Complete Writings 1959–1975 (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975), pp. 181–89.

12. Morris, Robert, ‘Notes on Sculpture’, reprinted in Gregory Battock (ed.), Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968), pp. 222–35.

13. Zelevansky, Lynn, and Laura Hoptman, in Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama, 1958–1968 [exhibition catalogue] (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 80-187.

Image and Cover Image Sources:

1. Yayoi Kusama's The Armchair (from Accumulation No. 1) on MoMA.